HMS Rodney was a Nelson-class battleship launched on 17 December 1925 and commissioned on 7 December 1927.

The design of the ship was approved six months after the momentous Washington Naval Treaty of 1922. This treaty, signed by the major naval powers of the time, aimed to limit the construction of capital ships in order to prevent another arms race like the one preceding World War I. Britain eagerly supported the initiative, as it was suffering from a post–World War I recession that complicated the upkeep and expansion of its fleet according to pre-war standards. The treaty explicitly listed the capital ships—defined as warships exceeding 20,000 tons of standard displacement or armed with guns larger than 8 inches (203 mm)—that each nation was permitted to retain. The total allowed tonnage was set at 525,850 for the United States, 558,950 for the United Kingdom, 221,170 for France, 182,800 for Italy, and 301,320 for Japan. Any other capital ships, whether completed or under construction and not named in the treaty, were to be scrapped. The U.K. was to scrap 20 pre-Jutland ships and 4 under construction. No capital ship was to exceed 35,000 tons or to carry a gun with a calibre in excess of 16 inches (406 mm). The two Nelson-class battleships were allowed to be completed, albeit with modifications to their original design to comply with the treaty’s limitations.

“The two Nelson-class battleships were allowed to be completed, albeit with modifications to their original design to comply with the treaty’s limitations.”

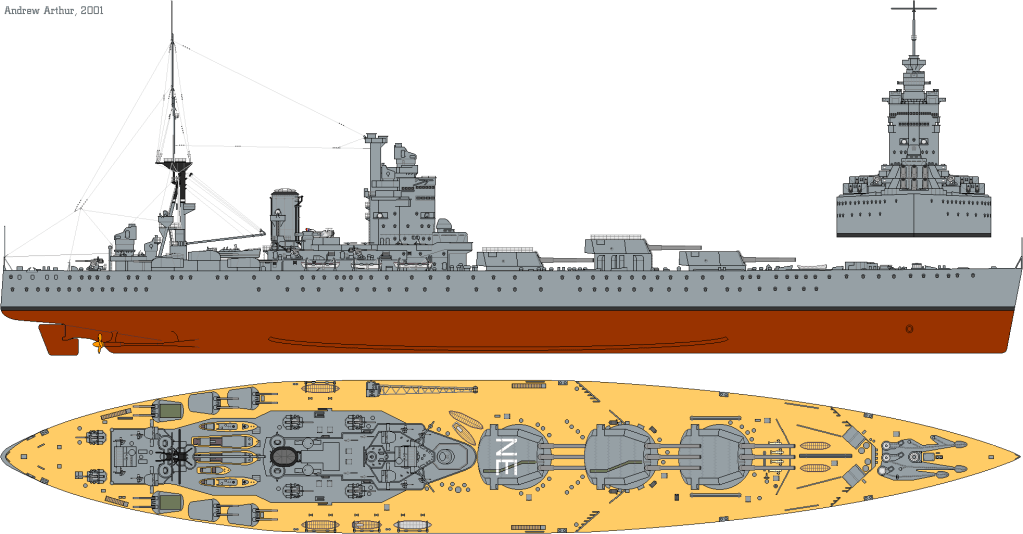

The Nelson-class was in essence a smaller version of the proposed G3 battlecruisers and was envisioned to reach a speed of 23 knots. This was made possible by her eight Admiralty 3-drum boilers which delivered steam to two Brown-Curtis geared steam turbines (45,000 shp (34,000 kW). Rodney and her sister ship were armed with nine 16-inch (406 mm) guns housed in three triple turrets, arranged in a unique configuration all forward of the superstructure. These 710 ft 3 in (216.5 m) leviathans had a standard displacement of 33,730 long tons, making them the largest battleships in the Royal Navy at the time. Her secondary armament consisted of six twin 6 in (152 mm) guns, six single 4.7 in (120 mm) AA guns, eight single 2 pdr (40 mm (1.6 in)) AA guns, and two submerged 24.5 in (622 mm) torpedo tubes. 1,361 officers and ratings were needed to keep the vessel operational when serving as a flagship and 1,314 as a private ship.

The Nelson-class battleships represented an innovative design, though heavily constrained by the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty. The combination of mounting 16-inch guns and adhering to the 35,000-ton displacement limit made weight reduction the designers’ top priority. Eustace Tennyson d’Eyncourt, the Director of Naval Construction, famously instructed designer Edward Attwood: “In order to keep the displacement to 35,000 tons, everything is to be cut down to a minimum.” This strict focus on weight saving led to compromises that adversely affected HMS Rodney’s performance during the Second World War. While HMS Nelson fared better—thanks to a series of refits before and during the war—Rodney suffered from numerous structural issues. Naval architect and historian David K. Brown observed: “It seems likely that in the quest for weight saving, the structure was not quite strong enough.”Unlike her sister Nelson, which exceeded her machinery weight specifications, Rodney’s lighter machinery caused persistent problems. Her endurance declined significantly during the Interwar Period. During the crucial 1941 pursuit of the Bismarck, Rodney even nearly had to withdraw due to fuel shortages. British naval designers later cited her poor range as a cautionary example when setting endurance requirements for the battleship Vanguard.

“In order to keep the displacement to 35,000 tons, everything is to be cut down to a minimum.”

“It seems likely that in the quest for weight saving, the structure was not quite strong enough.”

During the war, Rodney frequently struggled with leaks. Her 1941 refit in Boston came to no avail, as leaking and defective riveting continued to plague the vessel. By 1943, it was determined that a complete overhaul was necessary to keep her operational—a refit that never materialized as the war drew to a close.

Olivier Goossens

Leave a comment