After the victory at Barcelona, all remained quiet on the naval front in the Mediterranean. Despite the pressing need for a naval base, no further action was taken until 1707. By the summer of that year, momentum resumed for the Royal Navy as the Allies plotted their next major strike against France: Toulon.

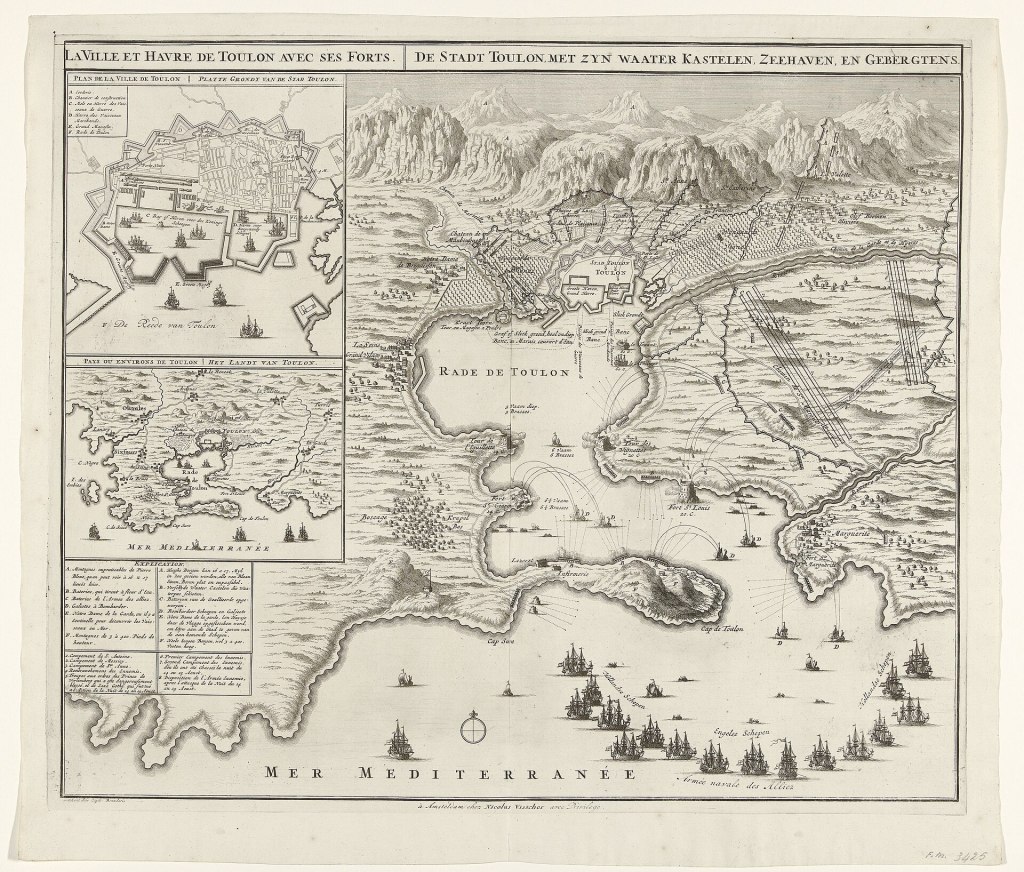

Situated along the southeastern coast of France, Toulon boasted an excellent, naturally protected harbor and had long served as the base for the French Mediterranean Fleet—a role it continues to fulfill today. Capturing this strategic port would not only resolve the Allies’ need for a naval base but could also bring the naval war in the Mediterranean to a decisive end. If executed correctly, an operation against Toulon could, in fact, result in the destruction of the French Mediterranean Fleet stationed there. Moreover, its capture would cripple Louis XIV’s ability to rearm his fleet, as Toulon housed crucial shipbuilding infrastructure and vital naval stores.

Beyond these naval considerations, there were other reasons for the Allies to mount an attack against Toulon. With this expedition, the Alliance hoped to divert Bourbon troops from Spain, where their pretender, King Charles III, was defending his claim to the throne against the Sun King’s grandson. Toulon’s capture would also better secure the Duchy of Savoy, one of the Allied powers, against future attacks from Paris. Finally, with a military presence in the port, the Allies hoped to encourage the Protestants of southern France to take up arms against Louis XIV, who, during his reign, had stripped them of the religious freedom granted by King Henry IV a century earlier.

The English were especially keen on marching on Toulon for the aforementioned naval reasons. As the Allies owed a great deal of money to England, they were in no position to turn down Queen Anne’s wishes. As we shall see shortly, Admiral Shovell, who represented Britain in the operation, always had the final say, which seriously complicated decision-making, as the expedition was primarily a land affair.

During the winter weeks of 1707, the Allies assembled a ground force of 35,000 men, which was ready for action by spring. The campaign was delayed, however, when Emperor Joseph I (r. 1705–1711) decided to divert some troops to Naples in June. This move was met with suspicion by the Duke of Savoy, Victor Amadeus II (r. 1675–1730), who had his own designs on southern Italy. Nevertheless, the Savoyard duke finally gave the green light to move out at the end of June, marching alongside the illustrious field marshal Prince Eugene at the head of 30,000 soldiers.

The Anglo-Dutch fleet supporting Duke Victor Amadeus and Prince Eugene was commanded by the seasoned Admiral of the Fleet, Sir Cloudesley Shovell. He was eager to contribute to the operation, as he believed Toulon’s capture not only offered strategic advantages but would also enhance England’s position in Levant trade. However, Shovell frustrated some of the Allied commanders, as he was expected to be off the North Italian coast much sooner. He had been held up in Spain after the Anglo-Portuguese forces suffered military setbacks against the Duke of Berwick. Shovell finally arrived off the Italian Riviera on 13 June aboard his flagship, HMS Association, leading a squadron of 47 men-of-war, 16 smaller ships, and 60 transports. Shovell’s second-in-command was Rear-Admiral Sir Thomas Dilkes.

On 7 July, the Allied commanders and their soldiers arrived in the shadows of the Maritime Alps, the southernmost point of this mountain range at the border between France and the Italian regions of Piedmont and Liguria. On 11 July, as the troops made camp near Nice, visual contact was established with Shovell’s squadron—a welcome sight for the troops, as it confirmed naval support, a crucial assurance of open lines of communication and provisioning.

On the other side, the French sensed that something was unfolding. When stores were bought up in Genoa, the French ambassador at the Italian port informed his compatriots that a military expedition was likely taking shape. Marshal Tessé, who had been transferred from Spain, was now commanding the French forces in the region. He shadowed the movements of Duke Victor Amadeus and Prince Eugene to determine their destination. After realizing Toulon was their objective, the French marshal marched at full speed toward the harbor.

Incredible efforts were made by the French to quickly prepare the town for a siege. Over the next few days, multiple detachments of infantry from different corners of Provence flocked into the busy city. Marshal Tessé set foot in Toulon on 24 July, just in time to take command of the defenses. A staggering 41 battalions—totaling 20,000 men—stood ready for battle by the time the 30,000 Savoyard-Austrian troops came into sight. Such a three-to-two ratio was but a meager advantage for the attackers and certainly not enough to ensure a swift conclusion to the siege.

Meanwhile, Tessé’s sappers worked tirelessly to strengthen the town’s fortifications, while extreme measures were taken to safeguard the French fleet. The holds of the French warships were flooded to make them more resistant to cannon fire and to prevent capture by the English. Their cannons had also been disembarked to assist in the harbor’s defense. This drastic measure effectively put France out of the naval war, as Louis XIV never again accrued enough funds to refloat his ships. It was an inglorious end to an inglorious campaign by the French navy.

Prince Eugene and Victor Amadeus arrived at Toulon on 26 July. An advance force of 300 grenadiers was sent to attack the French defenders atop Mt. Saint-Antony, whom they quickly drove off. The commanders of the Allied army then climbed Croix-Pharaon, a series of heights in the vicinity. To their astonishment, they observed how well defended Toulon was. Pessimism pervaded the minds of the officers. It became clear that Mt. Sainte-Cathérine and Sainte-Anne Camp were key to gaining access to the port city.

Prince Eugene was not entirely enthusiastic about the prospects of a siege. He feared the enemy’s numbers as well as the presence of militias in his rear. Admiral Shovell, however, entirely bent on taking Toulon, did his best to persuade his colleague to launch an attack, promising unconditional support from his squadron, which could quickly evacuate his men if things turned bad.

Prince Eugene finally gave in, and on 30 July, the fort on Mt. Sainte-Cathérine was stormed and captured. However, the number of troops under Marshal Tessé’s command in Sainte-Anne Camp to the north continued to swell. Further military action seemed like suicide. Prince Eugene pressed Admiral Shovell to give up, but the stubborn English commander would not budge. He had strict orders to take Toulon and was determined to see the wish of his Queen fulfilled.

As if the prospect of French reinforcements were not enough, the Allies lost a major trump card on the night of 14–15 August, when the French successfully retook Mt. Sainte-Cathérine. The Austrian-Savoyard forces lost one of their commanders during this battle, the Prince of Saxe-Gotha. A bit of momentum was regained, however, on 15 August, when the fort of Sainte-Marguerite opened its gates to the Austrian and Savoyard troops. This left only the fortress of Saint-Louis intact at the entrance of the harbor. Saint-Louis soon fell on 19 August.

The defeat of the harbor forts finally allowed Shovell to bring his warships within range of the city. The bombardment by the Royal Navy proved highly effective, causing much destruction. Yet, this proved too little, too late. It was only a matter of time before an overwhelming force of French reinforcements would arrive at Toulon. The Duke of Berwick had been recalled from Spain with several battalions to aid Marshal Tessé. Too little progress had been made inland to avoid a protracted siege. Furthermore, low morale, desertions, and scarce supplies further undermined Allied capabilities. Admiral Shovell finally gave in and agreed to a swift retreat.

One week after the French capture of Mt. Sainte-Cathérine, the Allied forces began turning back to Italy on the night of 21 August, after loading their sick and wounded aboard Shovell’s ships. Rear-Admiral Sir Thomas Dilkes provided cover for the withdrawal with a heavy bombardment of the city. Dilkes’s round shot and explosive shells wreaked havoc on the quays and storehouses, causing widespread destruction to the port’s naval infrastructure. Two French warships were completely destroyed, and many more were damaged. The shelling of the town lasted the entire day, while the Austrian and Savoyard troops waved goodbye to their unfortunate destination. Prince Eugene and Duke Victor Amadeus arrived safely at Nice on 31 August, while Shovell headed back to Spain. The Siege of Toulon was over.

The battle was universally viewed as a failure. Toulon remained securely in the Sun King’s hands, meaning Shovell and his colleagues still lacked a reliable naval base in the Mediterranean. There was one positive note to the expedition, however: the destruction of the French fleet. The Anglo-Dutch fleet reigned supreme and would continue to do so until the end of the war. The Siege of Toulon marked the definitive end of the French Mediterranean Fleet during the War of the Spanish Succession.

Olivier Goossens

Sources:

- Blackley, W., The Diplomatic Correspondence of the Right Hon. Richard Hill, 1845.

- Falkner, J., The War of the Spanish Succession: 1701-1714, 2015.

- Holmes, R., Marlborough; England’s Fragile Genius, 2008.

- Paoletti, C., “Prince Eugene of Savoy, the Toulon Expedition of 1707, and the English Historians: A Dissenting View”, The Journal of Military History, Vol. 70, 2006, pp. 939-962.

- Symcox, G., Victor Amadeus II: Absolutism in the Savoyard State, 1675-1730, 1983.

Leave a comment