From the skies over Eastchurch to the sands of Arabia, from the stormy northern seas to the scorching Indian Ocean, Charles Rumney Samson had a storied career that spanned the early days of aviation, the First World War, and the formative years of the Royal Air Force, playing a crucial part in each. He was a pioneer who brought naval aviation to new heights, and a trusted commander who led by example. Samson’s life is the stuff of Hollywood films — a source of inspiration, but, first and foremost, a key figure in understanding the rise of naval aviation. This is his life.

Early Years

Born to a solicitor on 9 July 1883 in Crumpsall, a suburb of the industrial city of Manchester, naval service wasn’t an obvious outcome for the young Charles. Nevertheless, at the age of 13, he ended up in the Royal Navy, enlisting as a cadet aboard the famed training ship HMS Britannia. He went on to become a midshipman two years later at the typical age of 15. He didn’t wait long to experience the full glory of the industrialized Victorian Navy, appearing in the records as midshipman of the Majestic-class pre-dreadnought battleship HMS Victorious in 1901. He finally became a commissioned officer the following year after successfully passing the lieutenant’s examination, being posted as sub-lieutenant aboard the protected cruiser HMS Pomone. He immediately got to enjoy the adventure that the navy offered, as the Pomone steamed into the warm, distant waters of the Persian Gulf.

He was enrolled in the navy’s books as a lieutenant on 30 September 1904. Many exciting commissions awaited Samson, as he first served aboard HMS Torpedo Boat 81 (originally named Swift), which, despite her age, could reach up to 23.75 knots with her three-cylinder compound steam engine. He was then allocated to the Edward VII-class HMS Commonwealth, before receiving the honour of becoming first lieutenant aboard the Pearl-class cruiser HMS Philomel, returning to the Persian Gulf with her. He continued his run as first lieutenant aboard HMS Foresight.

“His stout heart yearned to go where no man had gone before. He was in luck, as the Wright brothers had opened up new horizons for mankind just a few years prior by bringing controlled human flight within the realm of possibility.”

Samson, however, was looking for a new challenge. His stout heart yearned to go where no man had gone before. He was in luck, as the Wright brothers had opened up new horizons for mankind just a few years prior by bringing controlled human flight within the realm of possibility. When Samson, now in his steady early twenties, read about a vacancy to become an aviator for the navy, he applied along with 200 other young men, all poised to leave their mark in the annals of history. Unmarried, energetic, and talented, his potential was obvious, and he was granted access, along with three others, to the airstrip at Eastchurch to be instructed in the art of flight.

Samson passed his training, receiving his certificate from the Royal Aero Club on 25 April 1911. The navy’s impatience, combined with the dangerous simplicity of early aviation, meant that Samson received his degree after only 71 minutes of flight. Thus, in that short space of time, Samson had made a tremendous step forward in the history of British military aviation, putting his life on the line to learn the ropes of an emerging art. Samson and his peers had paved the way for future generations; it now became their patriotic duty to guide other Britons into the skies. He was made Officer Commanding of the Naval Flying School at Eastchurch in April 1912.

His finest moments as an aviator were reserved for the year 1912. On 10 January, he clambered into the cockpit of his Improved Short S.27, ready to take to the skies. There was one major difference from all his previous take-offs, however: the trusted grassy grounds of Eastchurch beneath his fuselage were replaced by a makeshift ramp attached above the guns of the battleship HMS Africa, anchored on the River Medway. Thus, Samson became the first Briton to fly an aeroplane off a ship, following the lead of the legendary American pioneer Eugene Ely.

Samson wasn’t satisfied, however, with simply treading in someone else’s footsteps. Instilled with the typical fervour of those early aerial pioneers, he wanted to take naval aviation to the next level. On 9 May 1912, he became the first man to get airborne from a moving ship when he took off from HMS Hibernia before King George V during that year’s Naval Review. He later repeated the feat two months later aboard HMS London. Samson wasn’t just a daredevil; he was also a man of admirable technical ability, leading the development of crucial techniques such as aerial wireless communication, bomb and torpedo dropping, navigational methods, and night flying.

“Samson wasn’t just a daredevil; he was also a man of admirable technical ability, leading the development of crucial techniques”

When the Royal Flying Corps was formed in May 1912, it was glaringly obvious that he was the right man to lead the newly formed Naval Wing. After the navy regained its independence with the creation of the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), he was put in charge of No. 3 Squadron in September 1914, leading the unit into the war that engulfed Europe in darkness. No. 3 Squadron initially operated from a place he knew well: Eastchurch.

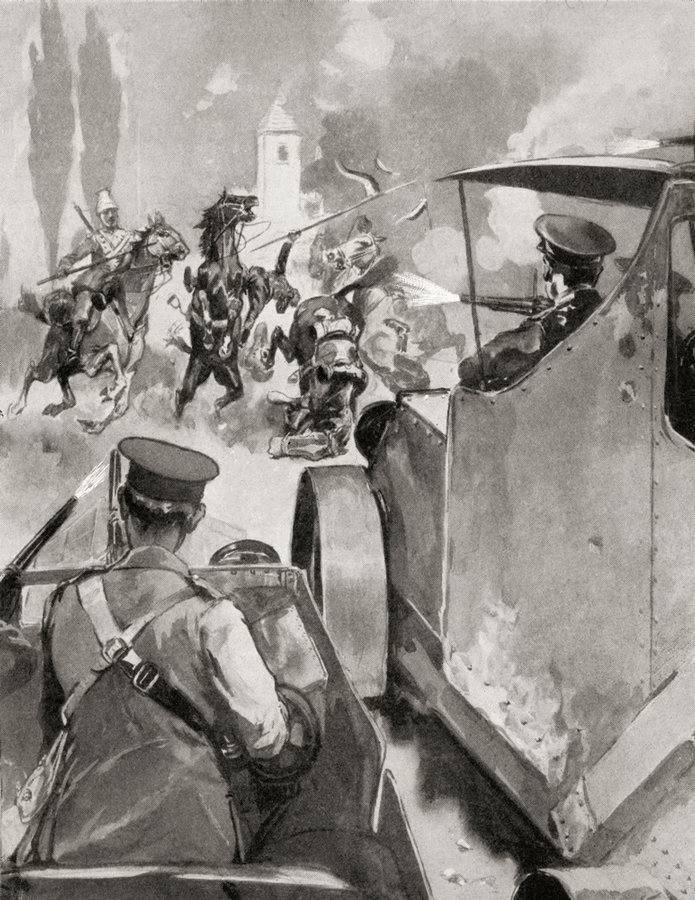

Samson and his men immediately travelled across the Channel with the British Expeditionary Force to support Allied troops in Belgium and France. Being responsible for reconnaissance along the front line, Samson possessed too few planes to carry out his mission. Instead, he used some of the private cars of his men to scout the German positions. Inspired by the success of Belgian armoured vehicles, he had some of his cars covered with hardened steel plates. Britain later officially adopted the idea, and heavily armoured cars built in Royal Navy workshops were shipped to the front line. Special armoured trucks were also ferried across the Channel, fitted with small openings through which Royal Marines could fire. Thus, the RNAS Armoured Car Section came into being.

Samson’s armoured cars proved their worth time and again. In cooperation with the Belgian post office and its telephone network, the cars sometimes drove deep into enemy territory to probe German dispositions. Their fearful presence often dissuaded the Germans from sending out cavalry reconnaissance of their own. These mobile units also assisted in battle, exploiting open flanks, covering retreats, and racing German forces to strategic positions.

As soon as No. 3 Squadron had reached full strength, Samson carried out numerous reconnaissance and bombing missions in occupied Belgium, sometimes even venturing as far as Germany itself to bomb the Zeppelin sheds at Cologne and Düsseldorf. By the end of 1914, his squadron had amassed four Distinguished Service Orders, and Samson was promoted to the rank of commander

Samson and Gallipoli

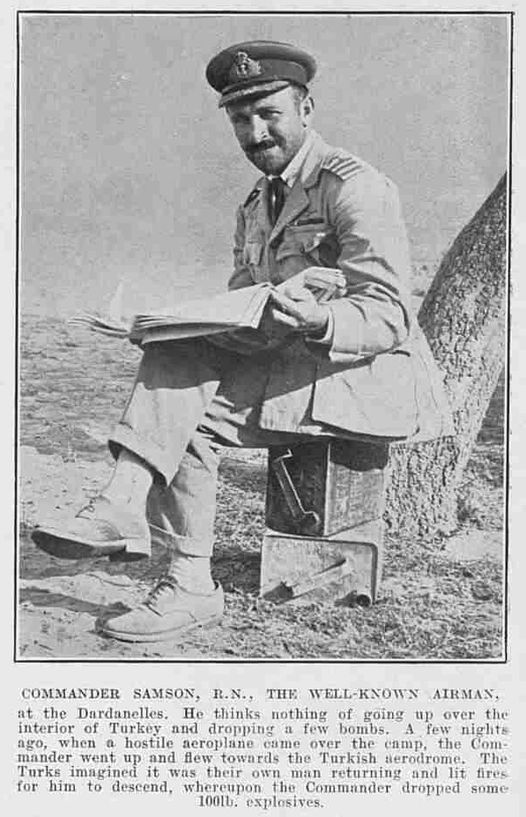

When the government agreed to Churchill’s plan of opening a second front in Turkey, Samson’s No. 3 Squadron was assigned to provide aerial support alongside the seaplanes of HMS Ark Royal. Samson, however, faced a grave shortage of serviceable aircraft, as it was found that only five of the thirty crated aeroplanes sent out were airworthy (consisting of B.E.2s and a Nieuport 10). During the disastrous Gallipoli campaign, Samson pioneered the use of radio from aeroplanes to direct naval gunfire, as well as the use of photographic reconnaissance. He carried out many of the missions himself, witnessing first-hand the carnage below. During the landings at Cape Helles on 25 April, he reported that “the sea was absolutely red with blood to fifty yards out” at V Beach. On 27 May, Samson spotted and attacked U-21, which had just sunk HMS Majestic. The commander dropped his bombs on the submarine but failed to score a hit, and then stubbornly emptied his rifle at the vessel to no effect. U-21 endured and survived Samson’s determined assault that day.

“He became a popular and uplifting figure among the British and ANZAC troops, cheerfully waving to his comrades before departing on his sorties into the clouds.”

After Cape Helles was secured at great cost, a temporary airstrip was constructed on the beachhead from which Samson’s squadron operated. He became a popular and uplifting figure among the British and ANZAC troops, cheerfully waving to his comrades before departing on his sorties into the clouds. In one of those strange historical ‘what ifs,’ Samson once attacked a Turkish staff car, managing only to damage the windscreen and injure no one inside. One can only wonder what might have followed had he scored a direct hit, for one of the occupants was none other than Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the future founder of the Turkish Republic.

In August, Samson’s operational freedom became constrained under the authority of Colonel Frederick Sykes, when No. 3 Squadron was placed under his command at Imbros. Sykes had previously criticised Samson’s handling of aerial support at Gallipoli, souring relations between the two men. Samson, however, ever the professional, set aside personal grievance and served loyally under his new commander until he was recalled to London in November.

Samson and the Arab Revolt

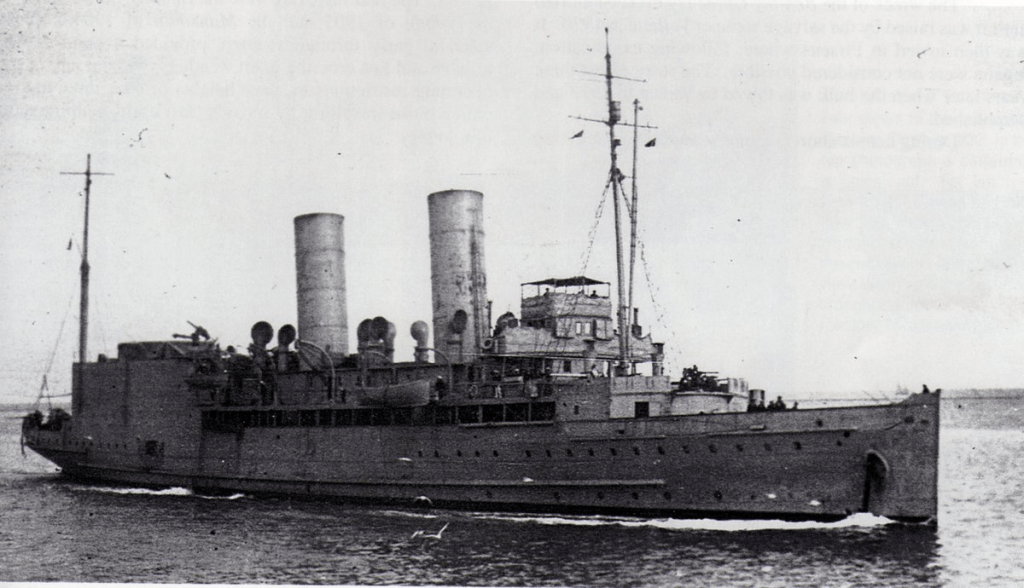

Samson’s story in the Mediterranean received its sequel on 14 May 1916, when he was made commander of the seaplane tender HMS Ben-my-Chree, a converted passenger steamer stationed at Port Said. The Isle of Man packet steamer was ordered up the Palestinian and Syrian coastline, assisting in the Arab Revolt and the British campaign against the Ottoman southern flank—particularly important since the offensive at Gallipoli had collapsed. Samson often flew himself in one of the ship’s seaplanes, scouting and strafing Ottoman positions across the Levant. He continued his aerial skirmishes against Ottoman positions in the Red Sea, where he arrived after transiting the Suez Canal.

His first target along the coast of modern-day Saudi Arabia was the Turkish battery opposite Perim, a small volcanic island off the Yemeni coast and part of the Aden Colony. Used as a coaling station, Perim was of particular strategic importance due to its position on the shipping routes linking the Red Sea and the Suez Canal. It had therefore long featured on the Ottoman “wish list” in their desire to disrupt British lines of communication. Their ambitions, however, were first checked by the bravery of the 23rd Sikh Pioneers, who repelled an Ottoman landing party, and later by the exertions of the Navy and Samson, who successfully silenced the Turkish guns aimed at the British station.

“At one point, the Admiralty requested an explanation for the extensive expenditure of ammunition by his unit, to which he famously replied that ‘there was unfortunately a war on.'”

The Ben-my-Chree then headed for Jidda, the next target of the Arab rebels. It was vital that this port city should fall into the hands of Hussein bin Ali, to serve as a supply base for the revolt. During the attack, Samson came under heavy Turkish fire, losing the heel of his boot and parts of his seaplane, but returned safely to his tender. The city fell to the Allies the following day.

Once the Arabian Peninsula was secured, the campaign continued into the Levant, and Samson returned off Palestine to resume operations there in what proved to be a remarkably busy period for the Ben-my-Chree. Here, he achieved a notable success by destroying a train carrying 1,600 Ottoman soldiers with his 16 lb bombs. At one point, the Admiralty requested an explanation for the extensive expenditure of ammunition by his unit, to which he famously replied that “there was unfortunately a war on.”

His time in the Eastern Mediterranean was brought to an abrupt end on 11 January 1917, when the Turkish pilot Mustafa Ertuğrul Aker sank the Ben-my-Chree while she lay in Castellorizo harbour. Ertuğrul Aker thus became the first aviator ever to send an aircraft carrier to the bottom of the sea. A subsequent court martial acquitted Samson of any responsibility in the affair. He was fortunate, however, that his two escorting vessels were already adapted for seaplane operations, allowing him to continue his eastern campaign, later patrolling the Indian Ocean from Aden and Colombo.

Back Home

In November of that year, Samson was finally recalled home, where he took command of an aircraft group at Great Yarmouth, tasked with hunting down Zeppelins and submarines. During his tenure in the North Sea, his group brought down five Zeppelins. Samson, however, desired to bring the fight closer to German shores and intercept their airships more rapidly. Working with John Cyril Porte, he designed a lighter that could be towed behind other ships and from which aircraft could take off closer to mainland Europe. His plan came to fruition on 11 August 1918, when Lieutenant S. D. Culley was awarded the Military Cross for shooting down Zeppelin L 53 after taking off from the lighter. Culley’s Sopwith Camel survives and is now on display in the Imperial War Museum.

As the war neared its end, Samson’s group became 73 Wing of the new No. 4 Group, a formation of the nascent Royal Air Force. Thus, Samson exchanged his naval commission for a permanent commission in the Royal Air Force, becoming the Group’s captain in August 1919.

After the War

In 1920, Samson served as Chief Staff Officer for the Coastal Area, and the following year he was appointed Air Officer Commanding of the RAF units in the Mediterranean, with his headquarters in Malta. He was promoted to air commodore in 1922 and took command of No. 6 Fighter Group at RAF Kenley in South London. Known for his exploits in the Middle East, it was a natural decision by the high command to appoint him Chief Staff Officer of the RAF’s Middle East Command in June 1926. That September, he led a flight from Cairo to Aden, departing on 15 September in two Vickers Victoria biplanes and returning to Cairo on 29 September. He later commanded an RAF formation of four Fairey III biplanes on a long-distance flight from Cairo to the Cape of Good Hope. He remained in the Middle East until August 1927.

Samson was placed on the retired list in 1929 due to ill health, and he died of heart failure at his home near Salisbury, Wiltshire, on 5 February 1931. He was buried at Putney Vale Cemetery on 10 February. He was married twice, and was survived by three children.

Olivier Goossens

Leave a comment