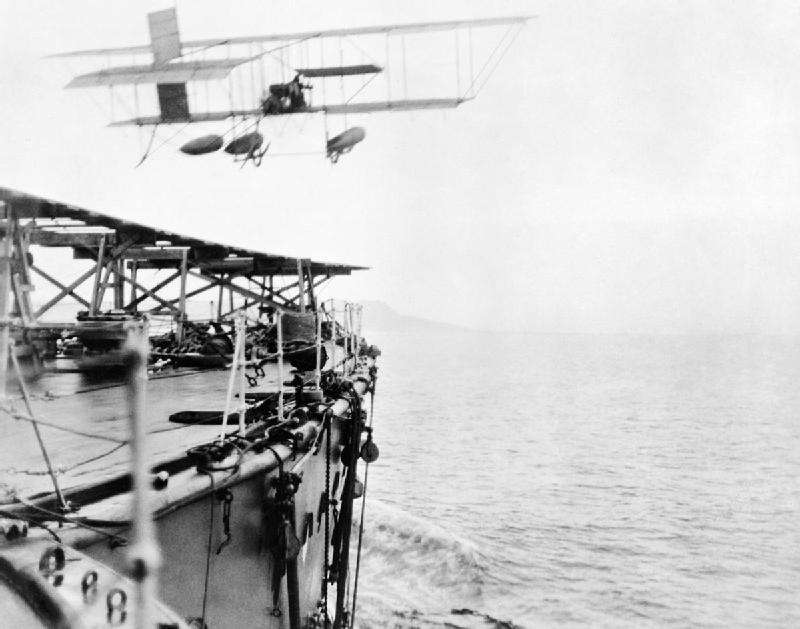

As soon as the Wright brothers took to the skies in 1903, one huge leap forward for mankind was made. Aviation soon became an international obsession, as American and European pioneers risked their lives to further refine the art of flight and secure new records. As with every developing technology at the time, the military also started looking into aviation as a potential asset. In 1910, the U.S. Navy took home the honour of launching, for the first time, a plane from a warship, as Eugene Ely took off from the USS Birmingham. The Royal Navy couldn’t afford to trail behind and initiated its own enquiries into aviation. By the outbreak of World War I, the navy could boast its own Royal Naval Air Service, possessing a respectable fleet of aircraft and airships capable of carrying out a myriad of tasks. It was, however, a long and winding road to get there. This is the story of the humble beginnings of the Royal Naval Air Service during those defining years of the dawning 20th century.

The history of the RNAS is traditionally traced back to 21 July 1908, when Captain Reginald Bacon, “the cleverest officer in the Navy,” submitted a suggestion to Lord Fisher to counter the German Zeppelins by integrating airships into the Royal Navy. Lord Fisher, himself continuously seeking new ways to innovate the fleet, quite fancied the idea. Bacon left the navy in 1909, however, and the task of establishing a naval air component therefore fell to Bacon’s protégé, Captain Murray Sueter, a Hampshire-born officer who had already amassed significant experience in incorporating innovation into the navy, having played a key role in the development of submarine warfare as a torpedo specialist.

“This was certainly a bad start for the navy’s aeronautic aspirations, but the event provided crucial data and valuable lessons for future designs.”

On 7 May 1909, the firm Vickers was contacted to design and construct the Royal Navy’s first rigid airship. The result was HMA (His Majesty’s Airship) No. 1, also known as the Mayfly, built in Barrow-in-Furness, Lancashire. The 156-metre-long Mayfly was allocated to the cruiser HMS Hermione, which was to act as its tender. However, due to strong winds, the airship broke in two before it could perform its maiden flight on 24 September 1911. This was certainly a bad start for the navy’s aeronautic aspirations, but the event provided crucial data and valuable lessons for future designs. However, Lord Fisher, now First Lord of the Admiralty, lost his trust in airships and preferred the development of aeroplanes. The Mayfly was therefore never repaired and succumbed to the elements in its shed. Only later, when the Germans’ cutting edge in airship design became glaringly obvious, did the navy renew its efforts to build up an airship fleet.

“The Admiralty then advertised a vacancy for four unmarried volunteers, reflecting the danger of the mission ahead.”

Meanwhile, by June 1910, the navy had welcomed its first qualified pilot, George Cyril Colmore, who held an aviator’s licence from the Royal Aero Club (RAC), the country’s chief aviation organisation. Many more were to follow. In March 1911, pioneer Francis McClean promised to lend the navy two biplanes so it could train its first generation of aviators. However, one of the two promised machines was lost over the Channel and was replaced with a new one, while a third, older plane was eventually also given to the navy. In short, McClean lent Short No. 26 Farman Type, No. 28 Farman Type, and No. 34 Farman Type. A further four planes were later added in 1911. The Admiralty then advertised a vacancy for four unmarried volunteers, reflecting the danger of the mission ahead. It should be remembered that aviation was still in its infancy and often ended in disaster or even death. Two hundred men eagerly applied, but only C. R. Samson, A. M. Longmore, R. Gregory, and E. L. Gerrard were accepted and enrolled in the training programme.

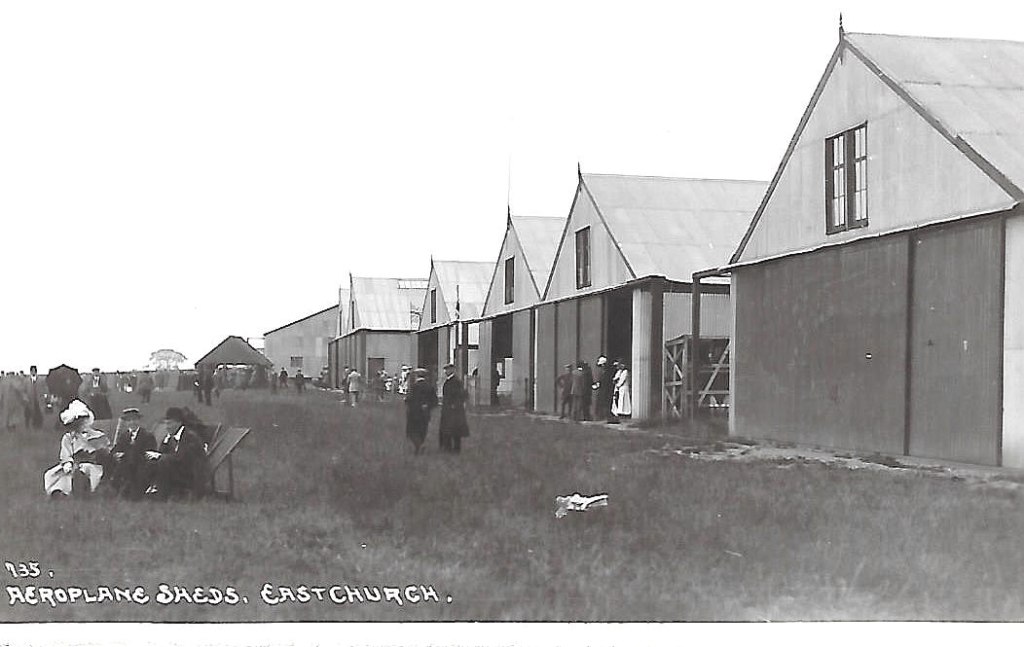

The first cadets arrived at the newly established Naval Flying School at Eastchurch, an airfield near Leysdown on the Isle of Sheppey, likewise kindly offered to the Admiralty by the RAC. Nearby was also the factory of the Short brothers—the nation’s first aircraft factory and the world’s first factory for the series production of aircraft. Eastchurch had by then already become a place of special significance in the history of British aviation, as John Moore-Brabazon had made his 500-yard flight there on 2 May 1909 in his Voisin biplane, regarded as the first-ever heavier-than-air flight on English soil. It was therefore most fitting that Britain’s first generation of aviators was to be educated there. They were introduced to the art of flight through instructors of the Royal Aero Club.

On 13 April 1912, the Royal Flying Corps was established by Royal Warrant of King George V. The sub-committee responsible for outlining its capacities decreed that the organisation should incorporate a Military Wing for the army and a Naval Wing, thus making the RFC a dual enterprise serving both the army’s and the navy’s needs and administered by both the Air Department and Directorate of Military Aeronautics. The pilots of the RFC were to be instructed at a central flying school, and the corps’ material needs were to be catered for by a single aircraft factory. The Naval Wing was placed under the command of the aforementioned Eastchurch graduate, C. R. Samson. The Central Flying School was established at Upavon, Wiltshire, and was commanded by naval officer Captain Godfrey Paine, although Eastchurch continued to be used for training naval pilots.

In the summer of 1912, a familiar face, Captain Murray Sueter, was entrusted with the further development of the navy’s aerial capabilities, becoming the head of the recently formed Air Department. From September of that year onward, the name “Naval Air Service” began to appear in official documents. Under Sueter, the navy stepped up its game. During the Army Manoeuvres of 1912, Sueter had four naval seaplanes participate. Later, in 1913, another significant step was taken when the navy’s warships conducted their first exercise with actual aircraft. During the exercise, the converted cruiser HMS Hermes acted as a seaplane tender. That same year, permission was granted for the construction of a seaplane base on the Isle of Grain and an airship base at Kingston. Plans were made to add a further eight airfields to that slowly growing list. By June 1913, 44 officers and 105 other ranks had been trained at Eastchurch and the Central Flying School, while a further 35 had been instructed in flying airships. Indeed, the navy also slowly reconsidered the use of airships in light of developments across the Channel and North Sea. Three non-rigid airships built for the army were transferred to the navy: the Willows, Astra-Torres, and the Parseval.

Two years later, on 1 July 1914—just weeks before the outbreak of World War I—the expanded RNAS officially emerged from the Aeronautical Department. Nevertheless, the Central Flying School was kept in place, with both naval and army aviators undergoing the same initial training and education. Broadly speaking, the RNAS was responsible for fleet reconnaissance, coastal patrolling, and coastal raiding with its aircraft and airships. It possessed 93 aircraft, 6 airships, and 2 balloons, operated and maintained by over 700 personnel. The Armoured Car Section was initially also under the RNAS’s care, with its Rolls-Royce armoured vehicles tasked with rescuing downed aircrews. The men of the RNAS acted with gallantry, earning the service two Victoria Crosses, while providing Britain with invaluable insights and innovations in naval aviation—thus establishing the backbone of what would become the Fleet Air Arm. How they fared during the war, however, is reserved for another day.

Olivier Goossens

Leave a comment