by Callum Easton

The name of this website comes from the chorus of the Royal Navy’s official march. Written in 1759, Britain’s ‘year of victories’, it boasts, ‘Heart of oak are our ships, Jolly Tars are our men, We always are ready: Steady, boys, Steady!’ It is a fitting song for a force whose many victories and swashbuckling exploits continue to fire the imagination over two centuries later. Yet, tucked between some of Britain’s most celebrated naval battles,1 spring 1797 found the Royal Navy far from ‘ready’, and its sailors anything but ‘jolly’.2

The Spithead and Nore mutinies were the largest in the history of the Royal Navy. They remind us that there was nothing inevitable or infallible about British naval success. The many victories were achieved by sailors with hopes, fears, and expectations. They had clear ideas about what constituted fair treatment, which they called ‘good usage’,3 and were fully capable of mobilising effective protest when required. In 1797, the state’s complacency — taking the seamen’s loyalty for granted — brought Britain close to disaster. Although catastrophe was ultimately averted, the crisis can teach us much about the British navy that would be missed from narratives centred exclusively on victorious battles.

‘Although catastrophe was ultimately averted, the crisis can teach us much about the British navy that would be missed from narratives centred exclusively on victorious battles.’

The nature and causes of the Spithead and Nore mutinies have been hotly disputed. This article presents a new interpretation that recognises ‘good usage’ as the key to understanding these remarkable events. The sense of grievance that drove sailors to mutiny in 1797 was not caused by hatred of the hardships of life in the navy. Instead, it was a growing feeling of neglect and unjust treatment that united the sailors in dissatisfaction. In short, it was ‘insult’ rather than ‘injury’ that drove these men to desperate measures.

In March 1797, Admiral Richard Howe received eleven petitions of complaint from the crews of the Channel Fleet.4 Howe forwarded these to the Admiralty for consideration but no action was taken. The sailors’ impatience grew. When the fleet was ordered to sea on 16 April, the seamen mutinied, took control of their ships, remained at anchor at Spithead (the stretch of water between Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight), and reiterated their demands. The Channel Fleet, Britain’s chief defence against invasion would remain paralysed for an entire month. The Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty entered into negotiations with the sailors and quickly conceded the justice of their key demands. These were the need for higher wages and larger rations of food. In return, the mutineers dropped some of their other demands and promised to make no more.5 Throughout, the sailors generally behaved respectfully to their officers (although some were compelled and others chose to go ashore). The mutineers did not allow ships to join the mutiny if they were needed to escort merchant convoys, and they promised to loyally engage any enemy fleet that dared put to sea.6 Gradually, all too slowly, the sailors’ core demands made their way through the political process. The delays bred suspicion and contributed to a short clash on 7 May, during which three men were killed on board the London. This focused the minds of politicians, who then rushed the necessary Bills through Parliament.7 The good news was delivered to the fleet in person by the popular Admiral Howe, who, on his own authority, agreed to replace 113 unpopular officers. The fleet at Spithead returned to duty amid a celebratory atmosphere, having won improvements to pay and food for all sailors across the navy. The squadron of the Channel Fleet at Plymouth remained in a state of mutiny for two further weeks before accepting the same terms along with the removal of 66 unpopular officers of their own.8

About a week before the Spithead mutiny came to its amicable conclusion, a supporting mutiny broke out among the rag-tag collection of ships at the Nore (an anchorage in the Thames estuary). This mutiny continued after the end of its precursor at Spithead, possibly, like at Plymouth, intending to remove some of their officers. The Admiralty initially hoped this new mutiny would soon peter out, but the arrival of most of the North Sea Fleet from Yarmouth bolstered the mutineers into a formidable force. Having, they felt, made generous concessions to the Spithead mutineers that benefitted all naval seamen, and fearful of setting a precedent that would lead to endless mutinies, the Admiralty resolutely refused to negotiate with the Nore sailors. Consequently, whereas the Spithead seamen had reduced their list of demands to reach compromise agreement, the Nore demands grew ever more numerous and outrageous as the mutineer leaders desperately tried to maintain support for the cause.9 In a chain of events reminiscent of Aesop’s fable of the sun and north wind, each attempt by the Nore mutineers to force the state to the negotiating table simply alienated and infuriated them (especially the brief mutineer blockade of the Thames!). Whereas the Spithead mutiny had taken a path of conciliation, the Nore led to confrontation and escalation. Finally, isolated and running out of supplies, the Nore mutiny collapsed in mid-June and 28 leading mutineers were executed.10

Theories about the causes of these mutinies have always fallen into two main strands. The first is that they were attempts at some kind of revolution instigated by foreign or domestic enemies of the British state. This theory can be discounted entirely, as we shall see below. The second is that the main causes of the mutinies are to be found in unpleasant conditions of naval life: mainly pay, food, and discipline. This theory is closer to the truth but also needs significant adjustment in order to explain the Spithead and Nore mutinies. In particular, we must shift the focus from the naval conditions themselves to sailors’ perceptions of fair treatment.

“Despite several determined attempts to portray them as such, the Spithead and Nore mutinies were not attempted revolutions.”

Despite several determined attempts to portray them as such,11 the Spithead and Nore mutinies were not attempted revolutions. None of the potential suspects had prior knowledge of the mutinies, and all proved utterly incapable of capitalising on them. Spring of 1797 was a terrible time for Britain and tensions were running high. Poor harvests in 1795 and 1796 had created high food prices and a wave of social unrest that made the authorities nervous. Abortive French landings in Ireland and Wales had recently highlighted Britain’s vulnerability and caused a financial crisis. Britain’s only remaining continental ally, Austria, was in the process of making peace with France. Only the navy seemed dependable. Only the navy seemed to offer safety and success.12 In this context, it is not surprising that the fleet mutinies caused such a profound emotional response and even felt like a betrayal of the nation itself. Some were quick to blame seditious or foreign influences, but these accusations do not stand up to scrutiny.

Firstly, the Foxite Whig Parliamentary opposition expressed their horror at the mutinies and were unable to take political advantage of them for fear of looking unpatriotic, or even complicit.13 Similarly, pro-reform groups like the London Corresponding Society had no influence over the mutineers, and none of the sailors’ demands related to Britain’s political structure.14 The French fleet at Brest was not seaworthy during the mutinies,15 and the French governing Council of Five Hundred continued to discuss the Royal Navy throughout as though it was an insurmountable obstacle.16 Nor are the United Irishmen or other groups opposed to British rule of Ireland credible instigators. Irish uprisings took place in 1796 and 1798, both timed to coincide with expected French landings, but nothing of this kind was planned for 1797. The Irish exile in French service, General Wolfe Tone heard about the mutinies while gathering forces in the Netherlands (the French Revolutionary satellite Batavian Republic). Despite his best efforts, no attempt to take advantage of the situation was made. His frustration is palpable in his diary, where he wrote, ‘damn it, damn it, damn it […] nothing was ready; that precious opportunity, which we can never expect to return, was lost’.17 This cuts to the heart of the matter. Paralysis of the Royal Navy fleets defending the home islands was too momentous an opportunity for any of Britain’s enemies to squander, which is compelling evidence they had no prior knowledge or involvement in them.

This leaves the naval conditions theory of causation. At first glance, this looks like an open and shut case. By 1797 the sailors of the Royal Navy had not had a pay rise in 144 years! — and they drew clear attention to this in their petitions.18 Most historians have considered this, combined with wartime price rise and poor harvests, as sufficient explanation for the Spithead and Nore mutinies. If we dig a bit deeper, however, the situation looks less clear cut.

For one thing, the sailors’ claim that they required higher wages to care for their wives and families, who would otherwise become ‘burdensome to the Parish’19 (reliant on local charity), is not entirely convincing. The vast majority of sailors were young and unmarried; 70% were 29 or younger, with 44% under 25.20 What’s more, an Admiralty official history of the allotment system (the process by which sailors could send part of their wages to family members) found that only 4.6% of sailors were even using the system in 1797.21 Seemingly family welfare was a pressing concern for only a small minority of seamen.

As for their own situation, the sailors were remarkably well insulated from price rises. Their food and accommodation were provided, they could purchase necessary items from the ship’s purser on credit, they received their physical pay only rarely, and their opportunities to actually spend money on shore were extremely few and far between. Furthermore, if we compare the timing of the mutinies with trends in prices of grains (wheat, barley, rye), we find that by the time the Spithead sailors were drafting their petitions, grain prices had returned to and remained at ‘normal’ levels for five months. By the time their mutiny actually began it was approximately seven months. Notably, the overall average price of wheat in January 1797 was only 52 percent that of the year before (January 1796).22 In short, the worst was far behind, current price conditions were favourable, and there seemed no immediate reason to fear an imminent return to higher prices. When all of this is taken together, the simple connection previously drawn between stagnant sailors’ wages, high prices, and mutiny starts to look decidedly shaky.

The solution to this conundrum is found in the sailors’ petitions themselves, which invite us to view wages not only as an economic issue, but also a social issue tied to pride and self-respect. Before making any complaints about prices or wages, the sailors stated it was now over two years since they ‘observed with pleasure’ the increases made to the pay of the army and militia. They had waited ‘Naturally expecting that they Should in their turn experience the Same Munificence’. Instead, they continued, ‘alas no notice hase been taken of them’.23 It is worth taking a moment to stress the injustice of this situation. Sailors had marketable skills that could earn them respectable wages on merchant ships, whereas most soldiers had less to offer. The army’s record in the war to date had been far from glorious, whereas what successes Britain had achieved were chiefly down to the navy (notably including the recent victory at St Vincent). In these circumstances, one can see why the perceived insult and injustice became intolerable for the sailors.

To make matters worse, naval lieutenants had been granted a pay rise in 1796, with captains due to follow in 1797. A far-sighted captain had written to the Admiralty in December 1796 to warn of the growing dissatisfaction among sailors and urging the state to increase their wages. His proposals were rejected on grounds of cost.24 Thus, it was not the rate of pay itself that drove the sailors to mutiny in spring 1797, but a shared fury that their services were being overlooked and undervalued.

“Thus, it was not the rate of pay itself that drove the sailors to mutiny in spring 1797, but a shared fury that their services were being overlooked and undervalued.”

Similarly, when we look at the other demands made by the mutineers at Spithead, and particularly those that they insisted upon in their negotiations with the state, the common denominator is fairness: ‘good usage’. The sailors’ petitions did not complain of being underfed and, indeed, the current consensus is that they received sufficient calories, even for their intensely active lives.25 Instead, they specifically complained about dishonest measurements. Naval rations were counted in pound-weight (lb), but sailors were issued ‘pounds’ of fourteen rather than the correct sixteen ounces. This was merely an officially sanctioned buffer to allow for inevitable wastage during long voyages. In calorific terms, the difference was not great but the perception of being cheated, of being told that fourteen was sixteen, and being expected to accept it, was a source of anger.26 In negotiations, the Spithead mutineers remained adamant that ‘we should have 16 ounces to the pound’ and the crew of Glory gave three cheers ‘for an Act of Parliament and an honest three pounds of pork’ [my italics].27 Likewise, the Spithead sailors expressed no complaints about the system of naval discipline per se and, for example, made use of flogging as a punishment themselves. Their grievance was with individual officers whose exercise of discipline was deemed excessive, inconsistent, or unpredictable, and these were the officers whose removal was demanded. Thomas Scott of the Sandwich, for example, wrote of the ‘Tyranny of Lieut. Archibald’ and James Wood of Cygnet complained that they had ‘a very bad Lieut.’ who was turned out of the ship.28 Rather than complaining about the overall severity of law and order in the fleet, the mutineers concentrated on individuals guilty of ‘ill-usage’.

This article has proposed a new way to understand the causation of the 1797 Spithead and Nore mutinies: the largest and potentially most dangerous in the history of the Royal Navy. Often in high-stakes disputes of this kind it is symbolic or emotional issues that most inflame opinion and prove the most intractable sticking points. Sometimes perceived insult hurts more than injury. Only if we place pride, self-respect, fairness, and ‘good usage’ at the heart of our explanation can we hope to understand the origins, scale, and significance of these momentous events.

Callum Easton

Abbreviations

BL British Library

NMM National Maritime Museum

TNA The National Archives, Kew

Readers might be interested to know that a more extensive explanation of the arguments advanced in this article can be found in my recent book: The 1797 Naval Mutinies and Popular Protest in Britain: Negotiation through Collective Action (Palgrave Macmillan, 2025).

- The Battle of St Vincent on 14 February 1797 and the Battle of Camperdown on 11 October 1797. ↩︎

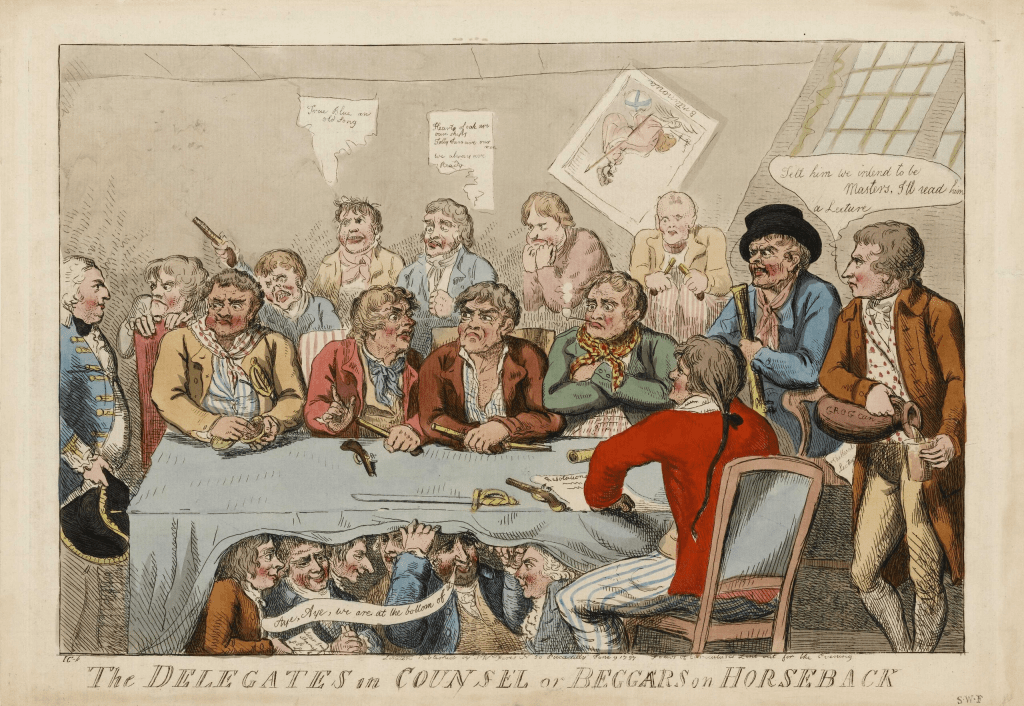

- The most recognisable image associated with the 1797 mutinies is the caricature ‘Delegates in Council’ by Isaac Cruikshank. It shows a meeting of mutinous sailors held in a captain’s cabin. Behind them on the wall are a set of posters including a picture of Britannia turned upside down and the words to ‘Hearts of Oak’ with ‘Ready’ crossed out. NMM PAG8535. ↩︎

- Letters from Captains, Surnames Y, TNA ADM1/2734, fol. 305; Steven Pfaff and Michael Hechter, The Genesis of Rebellion: Governance, Grievance and Mutiny in the Age of Sail (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), pp. 23–27, 105–11. ↩︎

- Petitions of Spithead sailors to Earl Howe c.28 February to 8 March 1797, Admiralty Petitions, 1793 to 1798, TNA ADM1/5125. ↩︎

- Petition from the Spithead Delegates to the Admiralty, 18 April 1797, Admiralty Petitions c.1793–1798, TNA ADM1/5125. ↩︎

- Letters from Commanders-in-Chief, Portsmouth: 1797, TNA ADM1/1021–23, fol. 356; Whitehall Evening Post, London, 20 April 1797; Sir Edward William Campbell Richard Owen, ‘Reflections on the Mutiny at Spithead’ (1825), NMM COO/2/a, p. 4. ↩︎

- Ann Veronica Coats and Philip MacDougall (eds.), The Naval Mutinies of 1797: Unity and Perseverance (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2011),pp. 27, 71. ↩︎

- N.A.M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean, A Naval History of Britain 1649–1815 (London: Penguin, 2005), p. 447; James Davey, Tempest: The Royal Navy and the Age of Revolutions (London: Yale University Press, 2023), p. 208. ↩︎

- Nore Letters, 1797, NMM HSR/Z/33/3. ↩︎

- Admiralty Rough Minutes, TNA ADM3/137, fols. 306–53. ↩︎

- E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (London: Penguin, 2013), pp. 183–85; Roger Wells, Insurrection: The British Experience 1795–1803 (Gloucester: Alan Sutton, 1983), ch. 5; Niklas Frykman, The Bloody Flag, Mutiny in the Age of Atlantic Revolution(Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2020), ch. 4. ↩︎

- As emphasised by victory at St Vincent on 14 February 1797. ↩︎

- See the speech by Richard Sheridan, The Parliamentary History of England (William Cobbett’s Parliamentary History), vol. 33, 3 March 1797–30 November 1798 (London: Hansard, 1818), p. 802. ↩︎

- An investigation by magistrates found no connection to any seditious groups. Report of Magistrates Mr Graham and Mr Williams, 24 June 1797, TNA HO42/41/68 fols. 213–14. ↩︎

- Reports of Captain Richard Keats and Mr Brummell, 21 and 24 April, 1797, BL Add. Ms. 35197, fols. 116, 123. ↩︎

- Gazette Nationale ou Le Moniteur Universel, 23 April, 5 May, and 25 June 1797. ↩︎

- Conrad Gill, The Naval Mutinies of 1797 (Manchester: University of Manchester Press, 1913), pp. 336–37. ↩︎

- Petition of the crew of the Queen Charlotte to Admiral Howe, 28 February 1797, Admiralty Petitions, 1793–1800, TNA ADM1/5125. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- J. Ross Dancy, The Myth of the Press Gang: Volunteers, Impressment and the Naval Manpower Problem in the Late Eighteenth Century (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2018), pp. 48–50, 64. ↩︎

- Report on the Allotment System in the Navy Compiled by Mr J. Pitcairn in the winter of 1857–58, TNA ADM7/719, Appendix 2. ↩︎

- The London Gazette, 3 January 1795 to 24 June 1797. ↩︎

- Petition from the crew of the Theseus to Admiral Richard Howe, 8 March 1797, Admiralty Petitions c.1793–1798, TNA ADM1/5125. ↩︎

- Julian S. Corbett (ed.), Private Papers of George, Second Earl Spencer, First Lord of the Admiralty, 1794–1801 vol. II (London: Naval Records Society, 1914), pp. 105–109. ↩︎

- Janet Macdonald, Feeding Nelson’s Navy, The True Story of Food at Sea in the Georgian Era (London: Chatham Publishing, 2006). ↩︎

- Gill, The Naval Mutinies of 1797, pp. 267, 369. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Helen Watt with Anne Hawkins (eds.), Letters of Seamen in the Wars with France, 1793–1815 (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2016), pp. 412, 429. ↩︎

Leave a comment