“As for those Cowardly captains who deserted you, hang them up, for by – they deserve it”

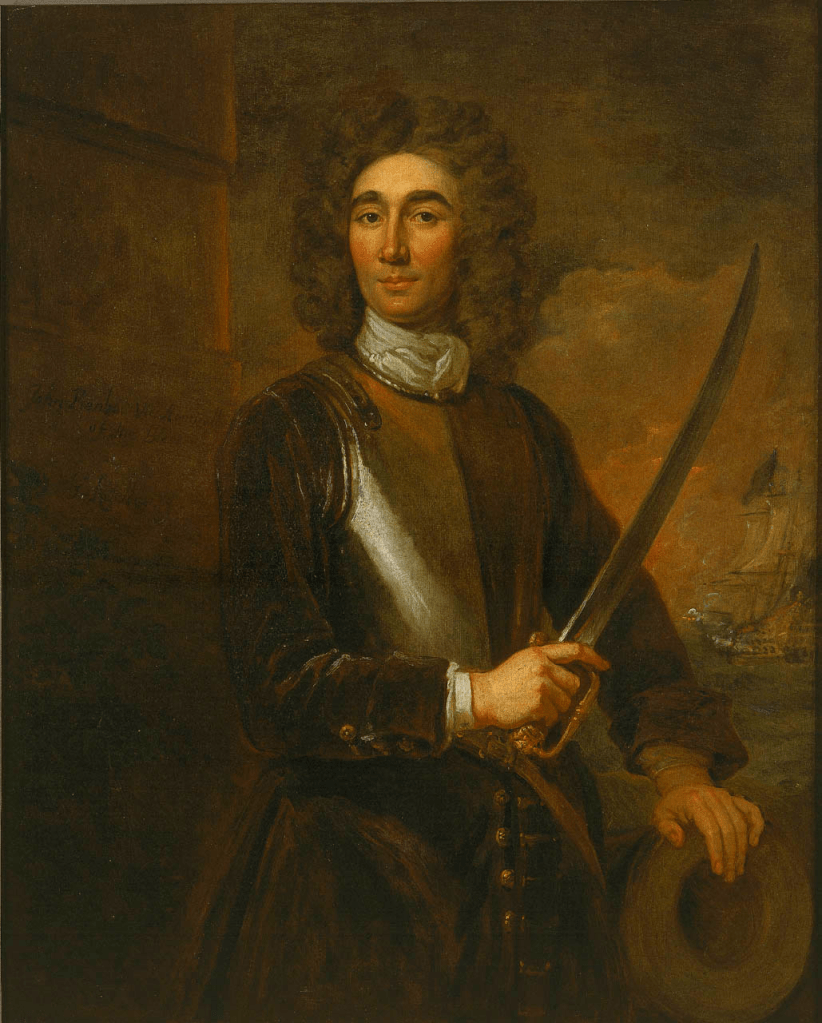

When England went to war with the Franco-Spanish alliance, led by the Bourbon royal house, the first concern of the island nation was the situation in the West Indies. Taking advantage of his kinship with the new Spanish monarch, French king Louis XIV managed to secure many trading privileges which allowed France to profit immensely from the mythical wealth of the Spanish main to the detriment of Dutch and English merchants. The Admiralty decided to commission one its most potent commanders to take care of the pressing situation across the Pond: Vice-Admiral John Benbow. For all his heroics, his campaign in the Caribbean would end in betrayal and disappointment.

Benbow’s Early Career

Born on 10 March 1653 to William and Martha Benbow, John’s early life is shrouded in uncertainty. Author John George Edgar claimed in 1861 that he lost his father while still a young lad, while his biographer D. Parkes wrote in 1819 that William had served in Charles I’s navy, meaning that John had the chance to enjoy his father’s company up until his formative teen years. The latter version could, in any case, explain John’s connection to the navy, which he joined in 1678. His early career saw some intense fighting against the scourge of the seas: the Barbary Pirates. Operating from the Maghreb, these Muslim corsairs cruised even beyond the Strait of Gibraltar, enslaving countless Christians and seizing the cargoes of many merchantmen.

In England’s war against the Algerine pirates in the Mediterranean, Benbow was posted aboard the 64-gun, Harwich-built, Anthony Deane–designed HMS Rupert, commanded by Captain Arthur Herbert. Benbow repeatedly impressed Herbert during the various actions against the North African warships, which only accelerated his climb up the navy’s hierarchy, becoming master of the 36-gun fifth-rate HMS Nonsuch by June 1679. He also made a lasting impression on other rising stars of the navy stationed off the Maghrebi coast, such as Cloudesley Shovell and George Rooke, whose connections further cemented his standing among the navy’s top officers. However, in August 1681, he clashed with Captain William Booth in a dispute over prize money after the capture of the Algerine Golden Horse. The subsequent court-martial ruled that Benbow owed Booth an official apology, and the Admiralty withheld three months’ pay.

After Nonsuch was paid off in England on 9 November 1681, Benbow exchanged the Royal Navy for the merchant service, entering the lucrative Levantine trade. His troubles with the Barbary Pirates were not over, however, as he was attacked by the so-called Salé Rovers, a group of corsairs operating from the Maghreb maritime republic of Salé. He successfully repelled the attack, earning further acclaim throughout the Christian world.

Benbow’s Return to Service

After the Glorious Revolution, Benbow returned to service, obtaining a post as third lieutenant aboard the 70-gun HMS Elizabeth. His first command came a year later, when he was given the captaincy of the 52-gun HMS York. Benbow’s career would once more intertwine with that of his old captain and patron, Arthur Herbert—now Lord Torrington—after being posted as his master aboard the first-rate HMS Royal Sovereign. He stood at Torrington’s side as master of the fleet during the infamous English defeat off Beachy Head on 10 July 1690. During the ensuing wave of inquests, Benbow produced evidence that strongly favoured his patron. He was subsequently present at Britannia’s revenge at the Battles of Barfleur and La Hogue, again in the capacity of master of the fleet. His exemplary conduct secured him the command of several flotillas of bomb vessels tasked with attacking the ports of St. Malo, Calais, and Granville. During these shore bombardments, he was recommended for promotion to rear-admiral by Lord Berkeley, whom he had thoroughly impressed during the attack on St. Malo. The relationship quickly soured, however, as Lord Berkeley became the scapegoat for the mixed results of the coastal operations, while Benbow was widely applauded for his boldness during the affair. As a reward, he was granted the pay of a rear-admiral and given an honourable seat on the board overseeing the construction of Greenwich Hospital.

When the Franco-Flemish privateer Jean Bart set out to harass English and Dutch shipping in the Channel, the navy promoted Benbow to Rear-Admiral of the Blue and placed him in command of a squadron tasked with destroying Bart’s marauding forces. Bart escaped the fury of Benbow’s broadsides, however, and made it to Dunkirk unscathed. Benbow was nevertheless retained to escort Britain’s incoming maritime trade from across the Atlantic with a squadron at the Soundings, while also being expected to occasionally reconnoitre the French coast until the war ended in September 1697.

Benbow in the West Indies

As soon as the war with Louis XIV was concluded through the Treaty of Ryswick, Benbow received a vital peacetime assignment: combating piracy in the West Indies. Although piracy had yet to reach the unprecedented levels of intensity it would during the late 1710s and 1720s, buccaneering in the Caribbean had already become a major concern for the government. Benbow set sail from England in November 1698 aboard his flagship, the brand-new, Bristol-built, 60-gun HMS Gloucester. During his passage to the Caribbean, his career briefly intertwined with that of one of the most remarkable figures of the age, the renowned astronomer and physicist Edmond Halley. Halley was likewise undertaking the long passage to the Americas to conduct scientific experiments in the North Atlantic aboard the navy’s first purpose-built research vessel, the 6-gun pink HMS Paramour, of which Halley, although a civilian, served as commander in the unique capacity of “temporary captain.” At the time, the Paramour was sheltering under the protection of Benbow’s guns from the ever-present menace of the Salé Rovers. Benbow’s squadron finally arrived in Barbados in February 1699 and moved on to Cartagena, where two English merchantmen were being held by the local governor. Under the threat of gunfire, the Spanish authorities relented and released the vessels to the determined admiral.

Benbow then continued to carry out his initial orders by hunting down pirates across the vast swathes of ocean off the American coastline. The pirates sped northwards, but Benbow soon followed their wake as far as Newfoundland, where he was unfortunately forced to call off the chase after the buccaneers had taken refuge in nearby harbours and inlets. He returned to England empty-handed in the summer of 1700. After a one-year spell under Admiral George Rooke at the Downs, he returned to the West Indies in September 1701, driven by a passion that usually derives from the sense of “unfinished business.”

By then Vice-Admiral of the Blue, Benbow was placed in command of a squadron of ten third- and fourth-rates. He directed his fleet from the quarterdeck of the third-rate HMS Breda (Captain Christopher Fogg), built at Woolwich Dockyard in the early 1690s. In anticipation of the looming War of the Spanish Succession, which became inevitable after the death of the Spanish king Charles II in 1700, he was ordered to search for and apprehend the Spanish treasure ships, a blow that would deal heavily against Madrid’s finances. The French, anticipating such a move by the English, countered Benbow’s deployment by dispatching a squadron of their own under the Marquis de Châteaurenault to protect the vital Silver Fleet. Châteaurenault’s sizeable force consisted of fourteen ships of the line, supported by sixteen frigates, thus outnumbering the English. Benbow was not deterred, however, and after receiving intelligence of the French presence, he energetically set about contesting their position in the West Indies.

The Battle of Santa Marta

Although Châteaurenault managed to slip from his grasp, Benbow finally had an opportunity to strike a blow against the French on 19 August 1702, when his fleet of seven ships of the line fell in with a French squadron under Rear-Admiral Jean du Casse. The French force, consisting of four ships of the line, one frigate, four sloops, and one transport, was spotted close inshore off the city of Santa Marta in the New Kingdom of Granada, today’s Colombia. Benbow was initially unable to give chase, as part of his force was still trailing behind. By the afternoon, around 4:00 p.m., his rear caught up, and he was ready to engage du Casse. His force consisted of the following ships:

- Breda (70 guns), Vice-Admiral John Benbow, Captain Christopher Fogg

- Defiance (64 guns), Captain Richard Kirkby

- Greenwich (54 guns), Captain Cooper Wade

- Ruby (48 guns), Captain George Walton

- Pendennis (48 guns), Captain Thomas Hudson

- Windsor (48 guns), Captain John Constable

- Falmouth (48 guns), Captain Samuel Vincent

Benbow’s action was, from the outset, marred by a shambolic display of disobedience and cowardice by his captains that day. The admiral’s plan was to overtake the French vanguard and knock their leading ships out of the contest before dealing with the rest. The Falmouth broke formation early on, however, to engage a Dutch ship sailing under du Casse’s command. The Defiance and Windsor followed suit, hastily engaging the nearest enemy vessels before withdrawing and remaining out of gunshot range. The vice-admiral became entangled in a fierce duel with the two sternmost French ships, lamenting the lack of support from his other vessels. The powdered dispute lasted well into the night, with the Breda finally withdrawing after taking considerable damage.

“Benbow’s action was, from the outset, marred by a shambolic display of disobedience and cowardice by his captains that day.”

“Then a chain shot from the enemy completely shattered the admiral’s right leg … Benbow, however, refused to sit out the engagement in the ship’s cockpit and returned to the quarterdeck, where he continued to direct his men from his cradle.”

When daybreak on the 20th heralded the resumption of hostilities, Benbow was dismayed to find only the Ruby nearby, with the other vessels straggling behind at a considerable distance of four to five miles. By afternoon, Benbow, now joined by the Falmouth, decided not to tarry any longer and continued his pursuit of du Casse. Much to his anger, he observed that the rest of his squadron still made no visible effort to link up with his vanguard. Nevertheless, he pressed on with the Ruby and Falmouth, harassing the French sternmost ships from a great distance without inflicting any significant damage.

Benbow’s relentless pursuit lasted for two days until a change in the wind finally allowed him to engage the French again. During the night of the 24th, the Breda came within gunshot range of the sternmost French ship, and a fierce action ensued. Benbow personally directed three boarding attempts, during which he was severely wounded in the face and arm. Then a chain shot from the enemy completely shattered the admiral’s right leg, and he was promptly carried below decks. The valiant and stubborn Benbow, however, refused to sit out the engagement in the ship’s cockpit and returned to the quarterdeck, where he continued to direct his men from his cradle.

The Breda’s unrelenting gunfire reduced her opponent to a complete wreck, but relief was at hand, as the remaining French vessels bore down on the Breda to assist their stricken comrades. The Breda disengaged after Benbow observed that his recalcitrant captains still remained far to leeward, making no visible effort to come to his aid. The English admiral exhorted them to turn toward the enemy and renew the engagement, but to no avail. Kirkby and the other captains were unwilling to continue the fight, erroneously believing that the French force outmatched them. Overwhelmed by this lack of resolve and their reluctance to follow orders, Benbow was forced to return to base in Jamaica. There, the valorous admiral succumbed to his wounds on 4 November.

“Overwhelmed by this lack of resolve and their reluctance to follow orders, Benbow was forced to return to base in Jamaica.”

He did live to see the day his insubordinate captains were brought to justice. Court-martials were conducted in October, and Captain Kirkby was convicted of cowardice, neglect of duty, and disobedience—all considered the gravest crimes for any serviceman in the navy. Captain Cooper Wade of the Greenwich faced the same charges, as well as the severe accusation of being drunk at the time of action. There was only one punishment deemed appropriate for such dastardly behaviour: execution by firing squad. Kirkby and Wade met their fate on the forecastle of HMS Bristol in Plymouth Sound on 16 April 1703, around 6 p.m. Captain Constable of the Windsor was relieved of the charge of cowardice and was cashiered instead. Hudson died just days before his trial, and the remaining two—George Walton of the Ruby and Samuel Vincent of the Falmouth—were exonerated for their support of the Breda during the action.

As for Benbow, he was celebrated as a national hero, regarded as one of the bravest officers of his day. In fact, the cabinet was preparing his promotion to Vice-Admiral of the White before news of his passing reached England. He was buried in St. Thomas Church, Kingston, with his tombstone reading:

“HERE LYETH INTERRED THE

BODY OF JOHN BENBOW,

ESQ, ADMIRAL OF THE WHITE

A TRUE PATTERN OF ENGLISH COURAGE,

WHO LOST HIS LIFE

IN DEFENCE OF HIS QUEENE

& COUNTRY NOVEMBER Ye 4

1702, IN THE 52nd YEAR OF

HIS AGE, BY A WOUND IN HIS LEGG

RECEIVED IN AN ENGAGEMENT

WITH MONSr DU CASSE BEING

MUCH LAMENTED.”

Olivier Goossens

Leave a comment