Historical Background

Although most of the heavy fighting of the War of Spanish Succession, which erupted in March 1701, took place in Europe, much was at stake in the West Indies. Trade with Spain’s colonies across the Atlantic was considered a potentially major source of income, one that had been poorly exploited by the motherland. When France and Spain became unified under one royal house, the Sun King Louis XIV obtained many trading privileges for the French from his new ally – something that upset many European powers, particularly England. England, in fact, had been vying for years with its nemesis across the Channel for the lucrative asiento, the monopoly on transporting African slaves to New Spain, which had now passed into French hands.

“When war broke out, one of England’s principal war aims became the disruption of French commercial power in the Americas”

Due to Spain’s poor naval capacity, France was also given the responsibility of escorting the much-coveted Spanish Treasure Fleet to Europe. Louis’ ministers took advantage of this, forcing the Spanish galleons to drop anchor in French harbours rather than Spanish ones. When war broke out, one of England’s principal war aims became the disruption of French commercial power in the Americas and the acquisition of the asiento. France, however, was not going to relinquish so easily its newly acquired mercantile supremacy in the West Indies and had been building up a sizable naval force in Martinique of about forty sail by 1702. Besides protecting the Treasure Fleet and French commerce, these ships were also tasked with attacking English possessions in the region.

London immediately sent Admiral Benbow in response to defend the country’s interests in the Caribbean. Although his presence deterred the French from attacking wealthy Jamaica, no decisive action occurred, and Benbow later succumbed to wounds received in a naval encounter off Santa Marta in August 1702. Thereafter, the Caribbean relapsed into a scene of uncoordinated mutual commerce raiding, in which the English suffered the most. The Bahamas were ravaged in 1703, St Kitts and Nevis endured heavy enemy raids in 1706, and later, in 1712, Montserrat in the Leeward Islands was pillaged. English counter-expeditions failed time and again, with Rear-Admiral Whetstone and Commodore Kerr’s squadrons quickly incapacitated by disease and hunger before achieving anything. It was Kerr’s replacement, Commodore Charles Wager, who would finally exact Britannia’s long-awaited revenge on 8 June 1708.

Charles Wager

Charles Wager, born in Rochester, Kent, in the ominous year of 1666, was connected on both sides to the navy. His father, who died shortly before his birth, had served in the Commonwealth navy under Oliver Cromwell and later switched allegiance to Charles II, who ascended the English throne in 1660. He had made a favourable impression on one of the central figures of England’s Restoration Navy, Samuel Pepys. After dining at the elder Wager’s home, the famed diarist and minister remarked that he was a “brave, stout fellow” whom he believed to be an honest man. Meanwhile, Charles’s mother was the daughter of William Goodsonn, a dutiful and steady admiral who never had the opportunity to embellish his reputation with a grand victory.

Charles Wager started out at sea as an apprentice to a New England captain in the merchant navy. It’s unclear when he commenced his career in the Royal Navy, but by 1689 we encounter him for the first time in navy records, listed as a lieutenant aboard the frigate Foresight. He got his first taste of the grand battles which characterized the age of sail at Barfleur in 1692. A year later 1693, Wager was placed in command of larger rates, captaining the Samuel and Henry of 44 guns. When the War of the Spanish Succession broke out, Wager was entrusted with the command of the third-rate HMS Hampton Court, which he called home for the next five years. Despite missing out on the enormous clash off Malaga in August 1704, Wager was present at several seminal events of the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean campaign such as the Capture of Gibraltar, the Capture of Barcelona and the later Relief of the besieged Catalan capital.

The competent and experienced Commodore Charles Wager seemed the perfect choice to take command of the troublesome Jamaica Station. He sailed from England in April 1707 with seven ships of the line, flying his flag aboard HMS Expedition (Captain Edward Windsor), a Portsmouth-built third-rate of 70 guns from the Restoration era whose timbers had witnessed some of the most intense naval battles of the 1690s. A few months later, in June, Wager arrived safely off the shores of Jamaica. His first concern was to ascertain the whereabouts and intentions of a French squadron under Admiral du Casse, which had followed the Kentish commander in his wake to the West Indies. Admiral du Casse had been tasked with escorting the precious Spanish American silver across the Atlantic. There were two key pick-up points: Porto Bello for the South American silver and Havana for the Mexican silver.

Tracking the Treasure Fleet

Wager’s squadron initially did not fare well, with two captains abandoning the commodore shortly after his arrival in the West Indies. Now commanding only five ships of the line, Wager, undeterred, remained determined to carry out his orders and headed for Porto Bello, the collection point of the South American silver. After learning that du Casse was away at Havana to leeward, he realized this was the perfect opportunity to organize a raid against the unprotected silver fleet to the west. These vessels habitually made landfall at Cartagena de Indias on the northern coast of Colombia after taking in the silver at Porto Bello, Panama. Wager therefore decided to intercept them off the Colombian coast during their approach to Cartagena. He promptly weighed anchor at Port Royal and set sail for his coveted target with four ships: his Expedition(70 guns), Kingston (60 guns), and Portland (50 guns), plus a fireship, the Vulture. Wager arrived at the Rosario Islands, some 30 miles west of the Colombian harbour, to take in supplies. He was, however, spotted by Spanish locals, who swiftly informed the governor of Cartagena, who in turn sent word to the silver fleet still at anchor in Porto Bello.

“After learning that du Casse was away at Havana to leeward, he realized this was the perfect opportunity to organize a raid against the unprotected silver fleet to the west.”

Warned of the English presence, José Fernández de Santillán, commander of the Spanish Treasure Fleet, nevertheless decided to take his chances and headed out into the open, setting course for Cartagena in the hope of evading the English along the way. This was no act of unwarranted hubris on the Spanish part, however, as the hurricane season was imminent. If the fleet lingered any longer, the weather would make any passage to the Iberian Peninsula impossible for 1708, and the timely arrival of the American silver was crucial for the Spanish war effort. The Spanish fleet consisted of fourteen lightly armed merchantmen, escorted by three galleons: the San José (64 guns), de Santillán’s flagship; the San Joaquín (64 guns); and the Santa Cruz (44 guns). Most of the gold and silver was loaded aboard the heavier galleons, while the merchantmen carried various other American goods in their holds. More specifically, the San José carried approximately 7 to 11 million pesos, the San Joaquín 5 million, and the Santa Cruz a far lesser amount.

The Action off Cartagena

On the evening of 7 June, the inhabitants of Isla de Barú, part of the Rosario Islands, caught sight of the seventeen ships silhouetted against the setting sun. The abating winds made any serious progress impossible for the next day, and by then it was already too late. Around 3 p.m., Wager’s squadron ominously appeared on the horizon, striking trepidation into Spanish hearts. Although defensive positions were assumed, the English knew where to look for the silver, bearing down on the three larger galleons.

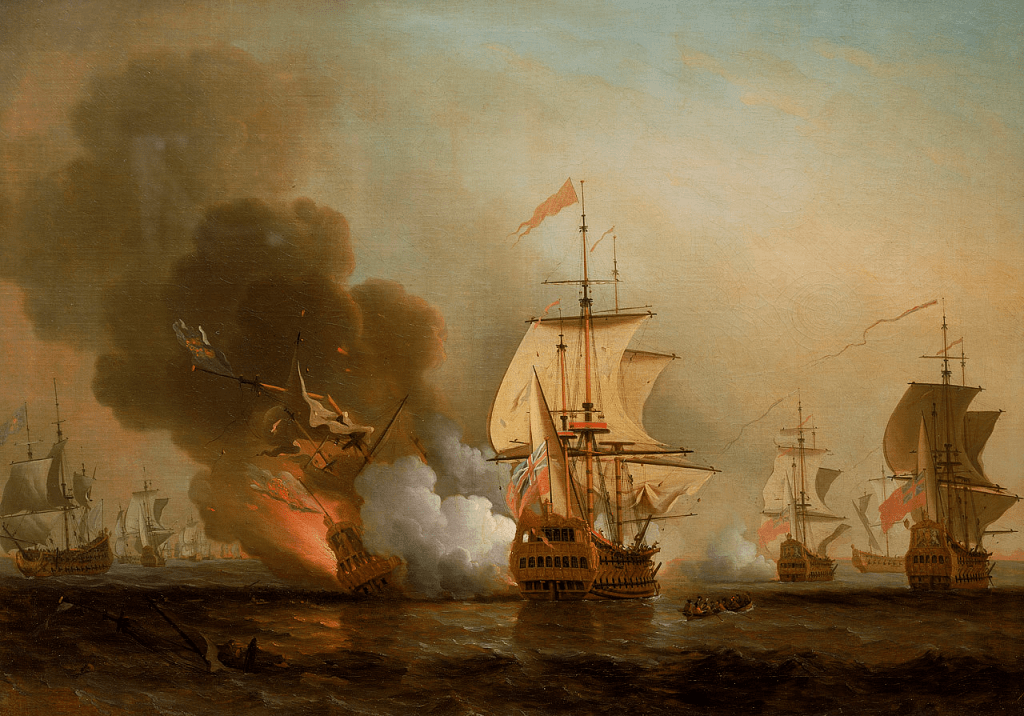

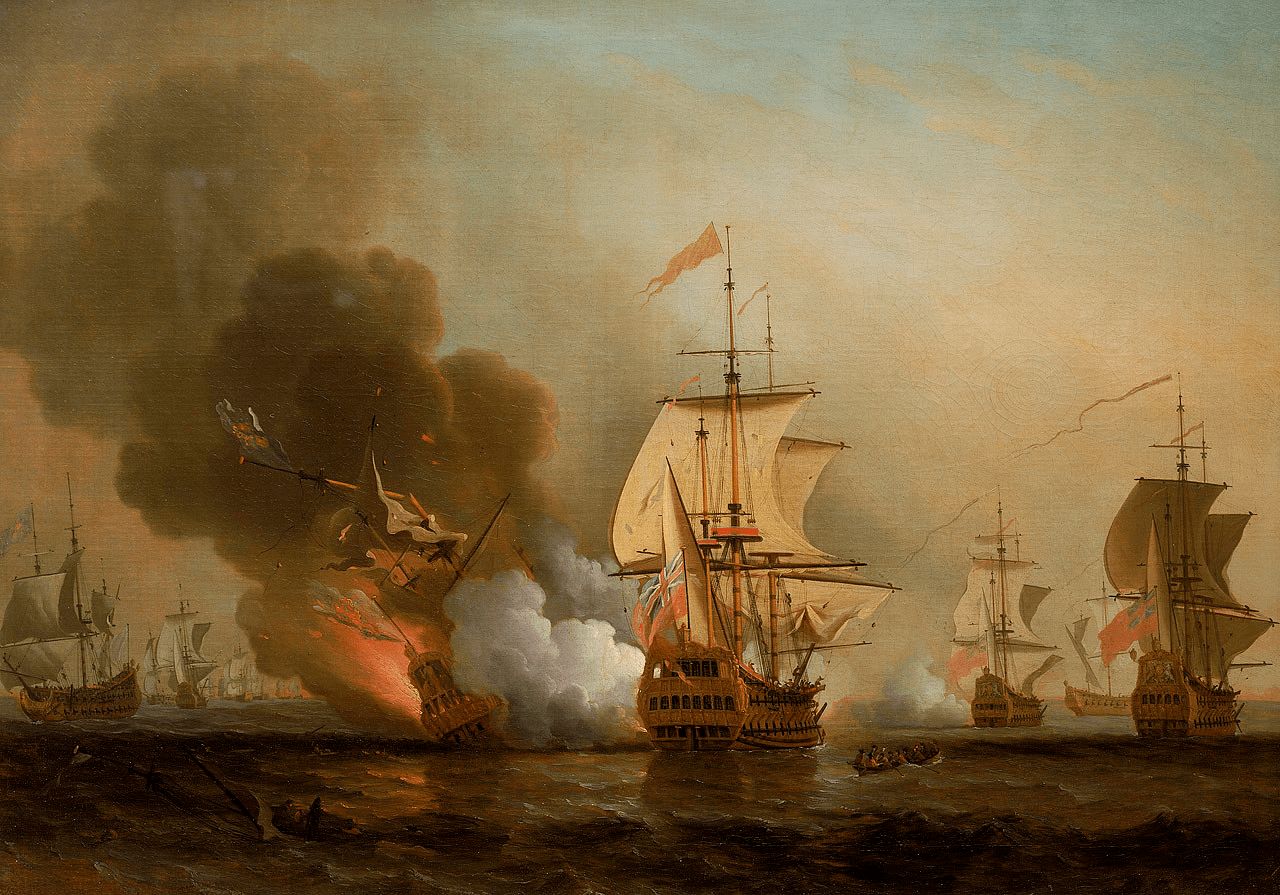

“Disaster struck the Spanish when a well-aimed broadside from the Expedition tore apart the San José“

Fire was exchanged around 5 p.m. between the Kingston and the San Joaquín, while Wager’s flagship targeted de Santillán’s ship, the San José. After two hours of heavy fighting, the San Joaquín managed to escape the clutches of the English, but disaster struck the Spanish when a well-aimed broadside from the Expedition tore apart the San José. Only eleven men of her complement of six hundred survived the cataclysmic explosion, which lit up the waters off Cartagena. Swiftly but silently, the San José slipped beneath the calm Meso-American sea, taking her valiant captain with her.

Once the pride of the Spanish Treasure Fleet, the only evidence of the stricken galleon’s existence was scattered timbers, illuminated by the last rays of the setting sun, gently brushing against one another and marking the graves of some six hundred men, now embraced by the eternity of the deep blue. The sudden demise of their opponent was no occasion for jubilation among the English, for soon the realization dawned that the San José’s much-coveted silver had accompanied the hundreds of poor souls to the bottom of the ocean.

Wager was not prepared to return home empty-handed, and there remained a chance for the English to capture the Santa Cruz. At 2 a.m., the commodore spotted the fleeing enemy, illuminated by the full moon. The rumble of cannon broke the silence of the soft night, and in the ensuing duel, fourteen Englishmen and ninety Spaniards perished before the Santa Cruz struck her colours. Much to the frustration of Wager and his men, the hold of the Spanish galleon contained a meagre booty of only thirteen chests of pieces of eight—a disappointing haul for men determined to claim the mythical riches of the Americas.

When the sun lit up the American skies again, the English spotted an opportunity to reverse their barren fortunes, as the San Joaquín was seen making haste for the safety of Cartagena. Wager ordered his smaller and faster Kingston and Portland to block the Spaniards’ entrance into the harbour, but the galleon outsailed the Englishmen, who swung around to stay clear of Cartagena’s guns. The rest of the Spanish squadron also escaped capture, except for the hulk Concepción, which, cornered by the British, ran aground on Barú Island and was set alight by her crew.

Conclusion

Wager had successfully crippled the Franco-Spanish war effort by preventing the Treasure Fleet from crossing to Europe. Although the booty from the Santa Cruz provided Wager with a life of comfortable financial security, he lamented the loss and escape of the other two galleons, which could have ensured his family’s fortune for generations to come. The English, recognizing the missed opportunity, scapegoated Captains Bridges and Windsor of the Kingston and Portland, who were court-martialled. Charles Wager, on the other hand, received a hero’s welcome upon his return, being knighted on 8 December 1709 and elected MP for Portsmouth in 1710.

“An estimated four billion US dollars of treasure still lies at the bottom of the sea”

The story does not end here, however, as an estimated four billion US dollars of treasure still lies at the bottom of the sea, earning the San José the well-deserved nickname the “Holy Grail of Shipwrecks.” The galleon was located in 2015 by the Colombian Navy, although the “Sea Search Armada” (SSA), a group of investors from the United States, claims to have found the ship as early as 1981, sparking an intense debate over the shares of the treasure. The Colombian government has recently rejected all SSA claims and has laid claim to the entire treasury, with the backing of US courts. The Colombian Navy is currently preparing to begin salvage operations on the mythical remains of the San José.

Olivier Goossens

Leave a comment