by Richard Hiscocks

There was not one officer in the Navy who was the equal in practical seamanship of Captain Sir Edward Pellew of the Indefatigable (44), and there were few that could match his personal courage, self-belief, or sheer presence. As a youngster he had undertaken gymnastic displays at the masthead for his captain’s guests, and as a frigate captain he had captured France’s finest vessel of that class, the Cléopâtre (40), and one of her biggest, the Pomone (44). He was the pride of the frigate commanders at sea, and of his beloved Devon and Cornwall at home, and it was thus most providential that Sir Edward and his wife were on their way to dine with a local vicar at Plymouth on the afternoon of 26 January when a ship with some five hundred people aboard drove ashore below the Citadel during a furious storm.

“Sir Edward and his wife were on their way to dine with a local vicar at Plymouth on the afternoon of 26 January when a ship with some five hundred people aboard drove ashore below the Citadel during a furious storm.”

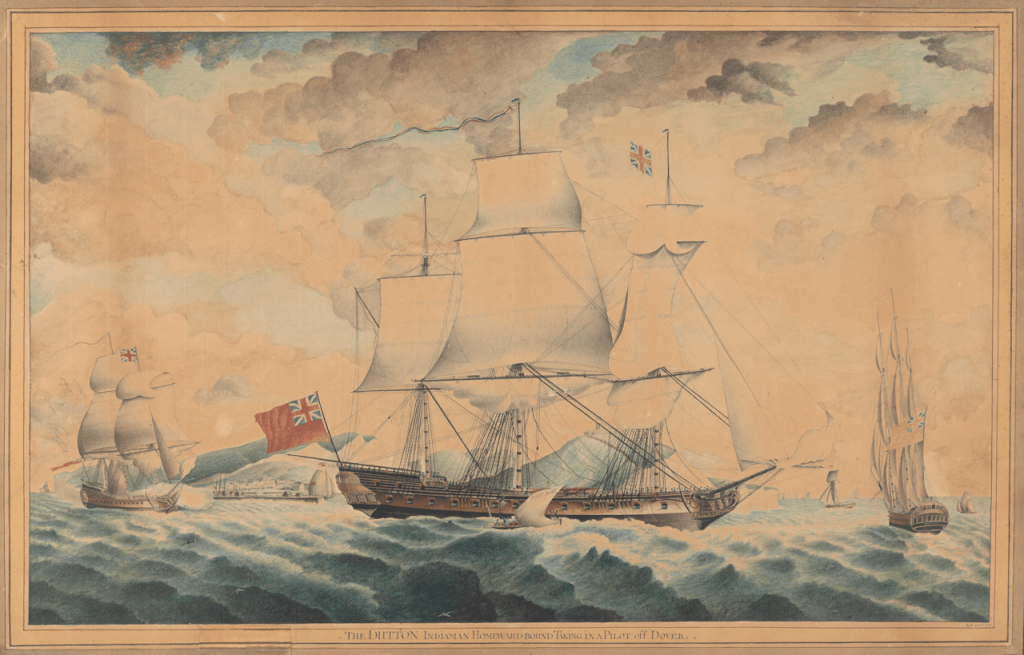

The vessel was a troop-carrying East Indiaman, the Dutton, Captain Peter Sampson, which was carrying several hundred troops bound for the West Indies from the 2nd, 3rd, 10th, and 37th Regiments, together with some of their families. Many of those aboard were ill with a fever, and the Dutton had reportedly lost thirty-five men to this sickness after sailing from St. Helens with a huge convoy on 9 December. Having separated from her storm-battered consorts to the west of the Bay of Biscay on 21 January, she had been forced into Plymouth Sound on the afternoon of the 25th, where she had managed to ride out a south south-westerly storm during the night whilst awaiting a tide to enter the Cattewater. Significantly, Captain Sampson had gone ashore that afternoon.

“At nine o’clock on the tempestuous morning of Tuesday 26 January, the Dutton began to drift towards the rocks at the western end of Mount Batten Island.”

At nine o’clock on the tempestuous morning of Tuesday 26 January, the Dutton began to drift towards the rocks at the western end of Mount Batten Island. Such was the violence of the storm that, unknown to the local pilots, the buoy on Cobbler’s Reef had been washed away, and in ignorance of her peril she grounded on a shoal at 11:15. Realising that if she drove ashore on the island all would be lost, her remaining officers slipped her cables and set a foretopsail in the hope of running for the Cattewater. In doing so they turned the ship’s head towards the Citadel, thereby enabling her to clear Mount Batten Point, but having lost the use of her rudder she became unmanageable, and she was instead blown helplessly across the harbour to strike onto sunken rocks just below the Citadel flagstaff at about 12:30. Here she bilged and began to fill with water.

In the hope of both forming an escape bridge to the shore and reducing the roll of the ship, the crew began to hack away at the masts. Unfortunately, before this task could be completed, the Dutton was thrust so violently against the rocks that the masts came crashing down of their own accord, fracturing uselessly as they did so. Now the ship heeled to one side, and the people thronging her deck found themselves swamped by the sea breaking over them. Some of the crew and soldiers did attempt to use the wreckage to scramble ashore, but this was a treacherous enterprise, and although most managed to clamber back aboard the ship, a handful who were hanging by ropes under the main chains were struck by the remains of the mainmast falling down upon them and killed. Another man perished when the bowsprit crashed down upon him.

Alerted by the Citadel guns firing out distress signals, and despite suffering from a partially healed wound, Captain Pellew jumped out of his carriage and made his way through a gathering crowd on the Hoe to the scene of the wreck. Observing the Dutton on her beam ends in the surf, he found that some people had actually managed to get ashore, having been hauled in on a single rope by local people who had come down to help, despite the danger of being swept off the rocks. However, it was clear that this was not only a particularly slow but also a dangerous process, for with the ship rolling and pitching in the surf, a man could find himself propelled some twenty feet into the air or be plunged below the heaving sea as the line alternately extended and retracted. Consequently, the hundreds of soldiers, sailors, women, and children still aboard the Dutton would dare not to take to the rope.

“ignoring the risk that the flood tide might completely wreck the ship, Pellew decided that there was nothing else to do but to be hauled across himself.”

As the raging storm increased with the accompaniment of a thunderstorm, Pellew’s attempts to communicate with the Dutton via a speaking trumpet were negated by the weather’s violence. He tried pleading for a volunteer from the Plymouth boatmen and pilots amongst the crowd to be swung aboard so that they could pass on his advice to the Dutton’s remaining officers, but none dare leave the safety of the shore, despite his offer of money to do so. Refusing to give in to the elements, and ignoring the risk that the flood tide might completely wreck the ship, Pellew decided that there was nothing else to do but to be hauled across himself.

Being dragged through the mountainous sea amidst the disintegrating and potentially lethal wreckage with the rope lashed around his waist proved immensely difficult for Pellew, not least because of his incapacitating injury. Much of his passage was spent under water, as the line could not be hauled taut to the shore in case it snapped under the strain of the stricken vessel. Eventually, he struggled aboard the Dutton and made his way up to the quarterdeck to announce himself. His very name and demeanour installed a calming influence on the panic-stricken throng assembled there, with a witness later claiming that his arrival was greeted by three cheers, both on the wreck and ashore. Yet not all aboard the Dutton were to be compliant, for a number of soldiers had broken into the spirit room and would only be returned to order once Pellew drew his sword and let it be known that he would cut down anyone who failed to adhere to his instructions. Even then, at least one soldier who still proved recalcitrant suffered the flat of the naval captain’s sword across his body before he fell into line.

“His very name and demeanour installed a calming influence on the panic-stricken throng assembled there.”

Now Pellew assembled a party which began to fix travellers and hauling lines to another hawser in order to speed the process of transferring people ashore. Shortly afterwards, a small boat with two brave men belonging to an Irish merchant brig came alongside to offer help, one of whom was her twenty-year-old mate, Jeremiah Coghlan. The youngster tied a rope around his body and jumped straight into the freezing waters, from where he dragged two men to the shore, repeating this feat to rescue several more. With fatigue overpowering him, Coghlan nevertheless had the wit to realise that by 2 p.m. the gale was abating, whereupon he raced around to the Barbican and commandeered another boat in which he was able to get near the wreck and take off more survivors. Come the end of the day, it would be estimated that Coghlan’s exertions alone had ensured the lives of fifty people.

“Pellew stood by the hawser, and with his sword still drawn he supervised the transfer ashore of the able bodied”

Back on the wreck, Pellew stood by the hawser, and with his sword still drawn he supervised the transfer ashore of the able bodied. By about 3 p.m. the storm had moderated enough for boats from the Indefatigable and the shore to come alongside the Dutton and take off the last three hundred and eighty or so women, children, sick, soldiers and crew, conveying them to a larger vessel which had come out from Plymouth Pool to help. Pellew stood sentry with his drawn sword to ensure that the boats were not swamped by people eager to make good their escape, and he personally carried a new-born baby down into one boat to hand it over to its grateful mother. Typically, he was one of the last men to leave the ship, along with two of the Dutton’s officers, and of course he took the hawser to the shore rather than wait to be evacuated by a boat.

By 5 p.m. the Dutton was full of water, and she toppled over after the last of the crew, but reportedly not a dozen or so desperately ill men in their hammocks, had been rescued. On the next day she broke up on the rocks with her lighter stores and casks being washed out of her. The number of people lost was never ascertained, but although it may have been up to twenty, it was thankfully hundreds less than might have been the case but for Captain Pellew.

Pellew’s bravery had taken its toll, and it resulted in him being confined to bed for a week. Nevertheless, his conduct saw him voted the freedom of the borough of Plymouth when the Corporation met at the Guildhall on the following Saturday, and weeks later he was created a baronet by the King. Somewhat appropriately, he chose an image of the stricken Dutton to decorate his coat of arms. As for the brave Jeremiah Coghlan, Pellew offered him a position aboard the Indefatigable, and it was an opportunity the Irishman seized to such effect that despite his humble origins, he rose through the ranks to become a post-captain.

Richard Hiscocks is the founder and co-author with naval historian Paul Martinovich of the ‘more than Nelson’ website, a biographical history and chronicle of the Royal Navy from 1776-1815. https://morethannelson.com/

Leave a comment