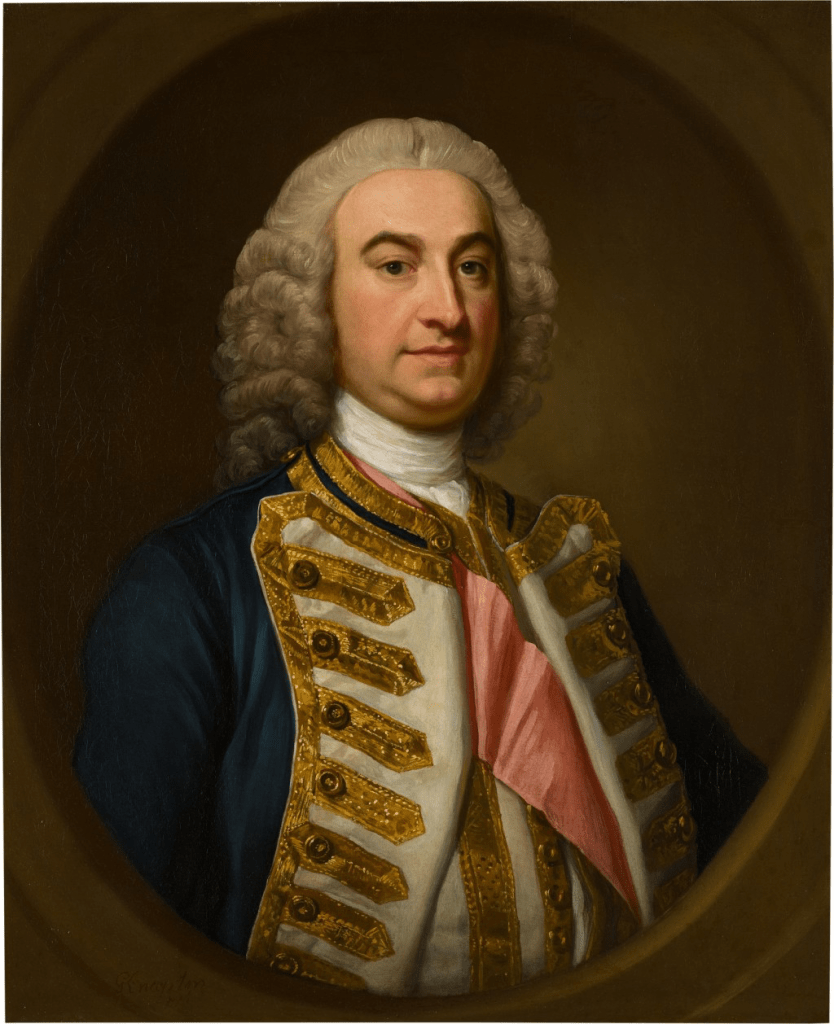

Edward Hawke was born on 21 February 1705 in the capital. He was the only son of a barrister-at-law of Lincoln’s Inn and his namesake, Edward Hawke, and Elizabeth Bladen, widow of Colonel Ruthven and sister of Colonel Martin Bladen, Yorkshire landowner, Member of Parliament, and Commissioner of Trade and Plantations. He became the ward of his influential maternal uncle after the passing of his father in 1718. Colonel Bladen would play a crucial role in opening up opportunities for the young lad. Edward entered the navy as a volunteer in February 1720 aboard HMS Seahorse, an eight-year-old Portsmouth-built frigate commanded by Captain Thomas Durell at the time. Hawke was destined to spend his first years at sea in the cold northern waters around Nova Scotia. Durell was in fact ordered by Richard Philipps, governor of Nova Scotia, to scour the area around his province. These surveys would form the basis for later maps of the island and the greater area. Seahorse later journeyed to the West Indies before crossing the Atlantic again in 1725. Back home, Hawke passed his examination for lieutenant in June of that year. Although his connections must certainly have helped him secure this promotion, one cannot help but suspect that he had already convinced his superiors of the extraordinary talents he possessed. He was afterward posted on HMS Kingsale, a fifth-rate ship commissioned for service off the West African coast and the West Indies. Later, in April 1729, he was transferred to the larger HMS Portland in the Channel Squadron, finally allowing Hawke to remain closer to home for once.

Mediterranean service followed for Edward in May 1731, when he set foot aboard the fourth-rate HMS Edinburgh as fourth lieutenant. He was later, in January 1732, off again to North America and the West Indies aboard the sixth-rate HMS Scarborough, commanded by Sir Peter Warren, who would later gain fame for the capture of Louisbourg in 1745. Sir Peter Warren was impressed by the young lieutenant and ever since looked after Hawke. While in the hot Meso-American waters, he was appointed first lieutenant of the 60-gun HMS Kingston, a ship with a fine career built in Kingston upon Hull and at that moment the flagship of Commodore Sir Chaloner Ogle, Commander-in-Chief of the Jamaica Station. Convincing his superior of his fine leadership qualities, Ogle decided to further advance Hawke’s career. Edward was given his first command in April 1733 of the sloop HMS Wolf. About a year later he was given responsibility for a larger vessel, HMS Flamborough, a post ship (a sixth-rate vessel smaller than a frigate) carrying 24 guns. He continued to command the vessel until she was paid off in England in September 1735, after which a period on half-pay ensued for Hawke.

Back on land, the seaman found time to start a family, entering marriage with seventeen-year-old Catherine Brook, the heiress to several estates in Yorkshire. The Brooks were no strangers to the Hawke family, as both households were already connected before through marriage. Seven children graced the wedlock, of whom three unfortunately died in infancy.

When war with Spain loomed over Britain, Hawke was ordered to sea again on 30 July 1739. He quickly set sail to the epicentre of the conflict, the West Indies, aboard a familiar ship, HMS Portland. The Portland was a fourth-rater carrying 50 guns which rolled down the slipway into the Thames at Woolwich on 28 March 1693. She had quite a career in her wake by the time she ended up in Hawke’s care. She had gained notoriety when she intercepted the Spanish Treasure Fleet off Cartagena on 8 June 1708 as part of Charles Wager’s squadron operating in the Caribbean. Later in the War of the Spanish Succession, the Portland recaptured the 50-gun Coventry in 1709. Hawke was to call her timbers home for the coming two years.

“Hawke, however, was far away from all the intrigue in the aftermath of the encounter, as he was one of the few captains to have acted with distinction.”

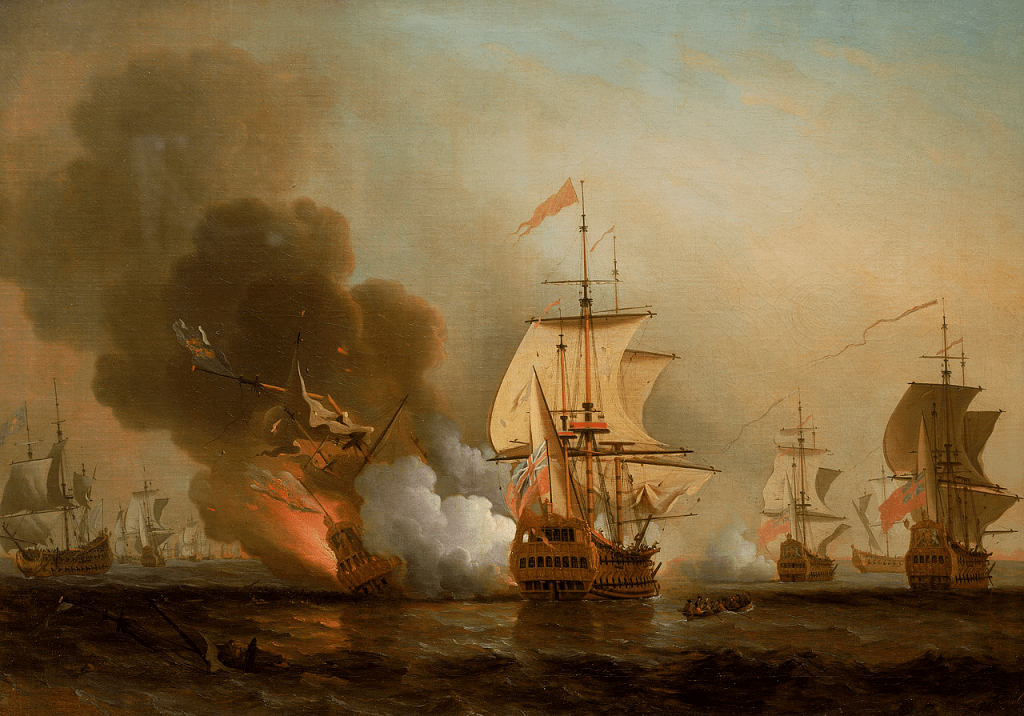

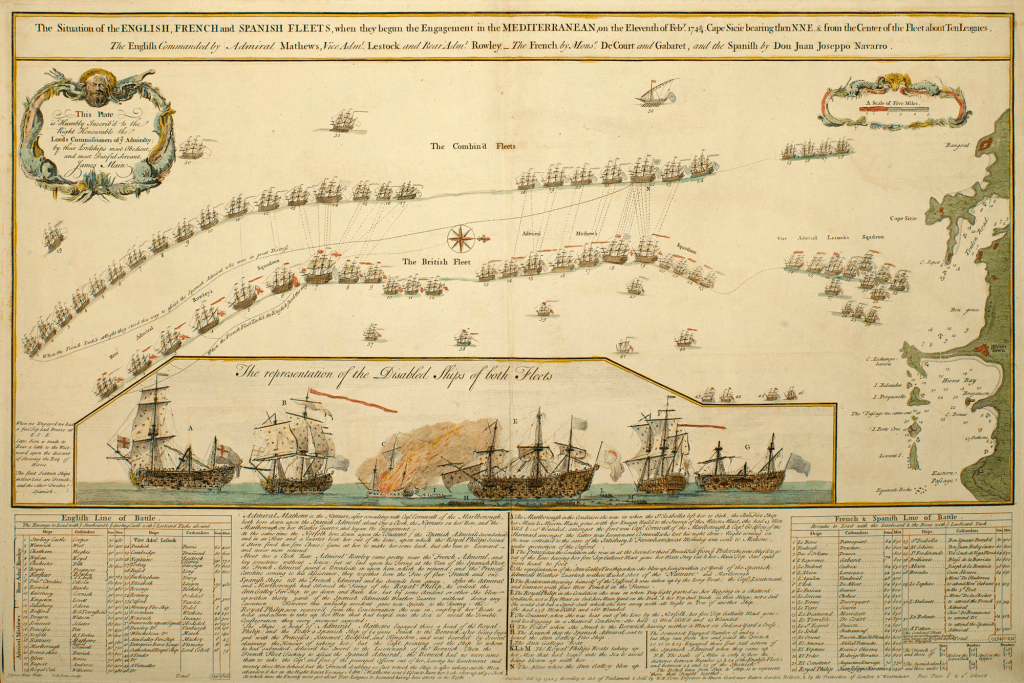

When cruising off Boston in November 1741, Hawke was caught in the clutches of a strong gale which blew away his ship’s masts. Luckily, the Portland managed to limp back to base in Barbados. Upon arrival, the weary captain was received by a welcome sight, as his wife had travelled all the way from England to join her husband in the Caribbean. The two travelled back home together in January 1742. The aged Portland was paid off and broken up. As the War of Jenkins’ Ear in the West Indies slowed down, England was sucked into an even bigger conflict which held all of Europe in its grip until 1748: the War of the Austrian Succession. Hawke immediately received a new command, the brand-new third-rate battleship HMS Berwick of 70 guns. He exchanged England for the sunny south, joining the Mediterranean Fleet under Admiral Thomas Mathews. Mathews was at the time blockading a trapped Spanish squadron at Toulon, led by Juan José Navarro. Although not officially at war, the French Levant Fleet sped to the succour of their Iberian allies. An infamous encounter erupted off the southern French port, which ended in a tactical draw and strategic defeat for the British. The commanders at the battle were at each other’s throats in search of a scapegoat. Hawke, however, was far away from all the intrigue in the aftermath of the encounter, as he was one of the few captains to have acted with distinction. He, in fact, engaged and captured the French 60-gun Poder, which was unfortunately shortly thereafter scuttled by Captain Richard Norris, the elder son of Sir John Norris. Hawke was rewarded for his gallantry and moved up the rating list, assuming command of the second-rate HMS Neptune in August 1745, in which he returned home.

When Hawke’s old patron, Sir Peter Warren, assumed command of the Western Squadron, he promptly appointed Edward as his second-in-command on 15 July 1747. Hawke raised his flag in the new fourth-rate HMS Gloucester as rear-admiral of the White. A little while later, Warren fell ill from scurvy, relinquishing his command to Hawke, who now was in charge of the central pillar of Britain’s naval defence—the heart of its “Wooden Wall.” Flying his flag aboard the third-rate HMS Devonshire, on 12 October 1747 the rear-admiral engaged a large convoy of East Indiamen off La Rochelle escorted by nine French warships in what came to be known as the Second Battle of Cape Finisterre. Although the majority of the merchantmen managed to evade capture, Hawke took six French ships of the line. The British later captured many of the escaped Indiamen in the West Indies after being informed of their presence by Hawke. This spectacular feat earned Hawke a Knight Companionship of the Bath (KB) and popular acclaim. He also entered politics in December that year as MP for Portsmouth, representing the borough until his elevation to the peerage in 1776, which barred him from further service in the House of Commons. When Warren was fully recovered and back on his feet, he was reinstituted as commander of the Western Squadron, with Hawke reverting to second-in-command. During the remainder of the Austrian War of Succession, Warren and Hawke cruised incessantly in the stormy Bay of Biscay. A few months later, Hawke was made vice-admiral of the Blue in May 1748 and officially took over command of the Western Squadron from Warren on 26 July 1748, serving in that capacity until November 1752.

Peace with France didn’t last long, as tensions in North America were never resolved. There, colonists from the Thirteen Colonies encroached upon French-claimed territory on the western frontier. This led to the unofficial French and Indian War in 1754. Hawke was deployed to prevent French supplies from reaching the Americas, raising his flag on the proud but ancient first-rate HMS St. George in February 1755, a Christopher Pett design launched some 37 years before Hawke was even born—almost double his age! After a fruitless cruise in the Bay of Biscay, Hawke was sent to the Mediterranean to save the British garrison in Minorca after John Byng’s squadron had been repelled in the infamous action of 20 May 1756. Upon arrival in Gibraltar, he hoisted his flag aboard the second-rate HMS Ramillies on 4 July 1756, only to learn of the British capitulation on the island, which had occurred on 28 June. Hawke was recalled to England later that year after a disappointing start to the war for him, only exacerbated by the death of his dear wife in October 1756. Nevertheless, Hawke continued to climb the hierarchical ladder, becoming admiral of the Blue on 24 February 1757—the third-highest rank in the Royal Navy.

“When William Pitt the Elder became Britain’s political leader in June 1757, the Seven Years’ War entered a new phase marked by a more aggressive naval policy, in which Hawke was to play a pivotal role.”

When William Pitt the Elder became Britain’s political leader in June 1757, the Seven Years’ War entered a new phase marked by a more aggressive naval policy, in which Hawke was to play a pivotal role. He was appointed to command the naval escort of the amphibious force set to make landfall at Rochefort in September. Sir John Mordaunt’s troops managed to take hold of Île d’Aix, just a few miles offshore Rochefort. The commander, however, decided against a subsequent attack on Rochefort, and the expeditionary force sailed home. This was the first—and certainly not the last—instance of Pitt’s new strategy of “descents” on the French coastline. Hawke led another raid against Rochefort on 5 March 1758, disabling coastal fortifications and preventing French reinforcements from setting sail toward Canada, which at that moment was the focus of Pitt’s offensive policy. Hawke thus contributed in no small measure to the capture of Louisbourg some five months later.

In the heat of the Seven Years’ War, a brief controversy threatened to upend Hawke’s excellent reputation. When the admiral got wind of Captain Richard Howe’s appointment to cover the next raid, Hawke struck his flag without permission in protest. He was infuriated by the Admiralty’s decision to pass over his usual command in favour of a mere captain. Summoned to the Admiralty’s headquarters to explain himself, Hawke embarrassingly learned that Howe had not been appointed to escort the next raiding party against Rochefort at all, but rather against St. Malo. Hawke’s respected track record as a naval commander saved him from serious repercussions for this act of indiscipline, but he was demoted to second-in-command of the Western Squadron, forcing Lord Anson, the First Lord of the Admiralty, to take over the mantle.

“He now entered a spell with the fleet that would not only define his career but also change the course of history. “

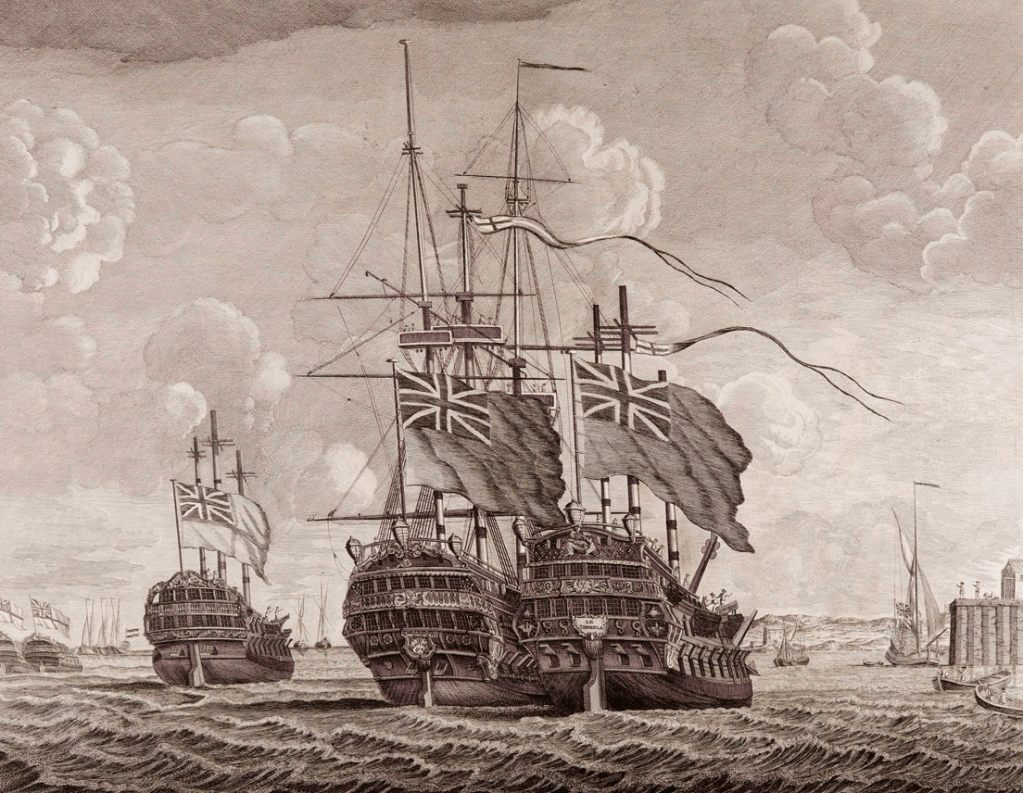

Hawke was reinstated on 9 May 1759, raising his flag aboard the legendary first-rate HMS Royal George. He now entered a spell with the fleet that would not only define his career but also change the course of history. The frustrated French government, effectively kept from their North American colonies by the British fleet, changed tack. Louis XV wanted to strike the island nation directly and focused all efforts on getting his army across the Channel onto English soil. An invasion force was being assembled at Quiberon Bay, which the new commander of the Brest fleet, Comte de Conflans, was to escort to the British Isles. When Hawke was forced to leave his station off Brest due to a strong autumnal gale, the Comte seized the opportunity and headed south to pick up the transports. As soon as Hawke was informed of the French escape, he promptly weighed anchor and shepherded his squadron out of Torbay into the tempestuous Bay of Biscay, determined to crush the enemy. Inspired by a fervour which would later be echoed by Nelson, Hawke relentlessly chased Conflans through storm-force winds amid the shallows and razor-sharp rocks that dotted Quiberon Bay. The admiral is said to have replied to his ship’s master, who warned him of the perils: “Master pilot, you have done your duty—now lay me alongside of the enemy.” He caught up with the French and engaged them in a battle so dramatic and intense, it would hardly be believed if depicted in a Hollywood picture. Hawke captured seven French ships of the line for the loss of two of his own and routed the rest into local estuaries. This triumph, together with Boscawen’s victory off Lagos, completely eliminated French naval capabilities. It sealed the fate of New France, which—cut off from reinforcements and supplies—slowly bled to death. After the conquest of Montreal the following year, the British conquest of Canada was complete. The Battle of Quiberon Bay has therefore been hailed as one of the most important naval victories in British history.

After his tremendous feat amid the rocks of Brittany, Hawke remained with the Western Squadron until January 1760. After a brief spell in England, the admiral returned to his usual station in August aboard his trusted flagship, the Royal George. Even after such spectacular victories, Britannia did not rest on her laurels. An invasion of Belle-Île was being prepared, an island situated just 8.7 miles (14 km) from the scene of Hawke’s finest hour, the Quiberon Peninsula. Hawke remained in charge of the blockade during the winter of 1760–61 until he was relieved in March, just a month before the expedition against Belle-Île was launched. The operation was a success, and the French forces surrendered to General Studholme Hodgson eight weeks later. A year on, in April 1762, Hawke was made commander-in-chief of all naval forces in the Irish Sea, Soundings, Bay of Biscay, and the Channel. In June of that year, he was ordered to Ferrol, Spain, to make sure the local Spanish squadron didn’t get any funny ideas after war had erupted in January. Later that year, on the auspicious day of 21 October, Hawke was promoted to Admiral of the White, the second-highest rank in the navy.

“The Seven Years’ War finally came to an end in February 1763 with the Treaty of Paris. Britain had emerged as a true world empire, with sovereignty over the seas. Hawke’s leadership throughout the war had been instrumental”

The Seven Years’ War finally came to an end in February 1763 with the Treaty of Paris. Britain had emerged as a true world empire, with sovereignty over the seas. Hawke’s leadership throughout the war had been instrumental, and the nation reserved a central role for the admiral in the peacetime years to come. In December 1766, Hawke succeeded the short-lived Charles Saunders as First Lord of the Admiralty in the Duke of Grafton’s cabinet. He retained this post after the fall of the government in January 1770, a collapse largely due to an ill-managed foreign policy in the Mediterranean. Meanwhile, in January 1768, Hawke had attained the highest rank in the Royal Navy—that of Admiral of the Fleet.

It was under Hawke’s tenure as First Lord that the first of James Cook’s first voyage was undertaken. During a meeting of the Royal Geographical Society, it had been suggested that a civilian should lead the expedition—an idea that Hawke abhorred. He subsequently mobilised all his influence to secure Cook’s appointment. As a sign of gratitude, Cook named several places after the First Lord of the Admiralty, most notably Hawke’s Bay on New Zealand’s North Island.

Typical peacetime cuts to the navy’s budget made Hawke the scapegoat of many dissatisfied seamen during his tenure, as reflected in the popular jingle:

“Ere Hawke did bang Mounseer Conflang

You sent us beef and beer.

Now Monseer’s beat, we’ve nought to eat

Since you have nought to fear.”

Britain’s new Prime Minister, Lord North, eventually put a stop to the economising policy after the Falklands Crisis of 1770, during which Hawke swiftly mobilised the navy to secure a diplomatic victory over the Spanish. Nevertheless, Hawke remained in Lord North’s cabinet only for a short while, and was succeeded by Lord Sandwich in January 1771.

On 20 May 1776, Hawke was elevated to the peerage, receiving the title Baron Hawke of Towton, a Yorkshire parish where his residence, Scarthingwell Hall, was situated. He also had a country house built in Sunbury-on-Thames, a town on the north bank of the Thames southwest of London. He spent his time alternately there and at a rented house in North Stoneham, Hampshire.

His final years in retirement were marred by continuous health issues such as gout and urinary calculi—an illness resulting from vitamin A deficiency and a shortage of fresh water. Later, he also had to bear the burden of many family tragedies, including the declining mental health of his daughter Kitty. In October 1773, he grieved the loss of his second son, Lieutenant Colonel Edward Hawke, who died while hunting. Just four years later, in September 1777, he lost his third son, Cornet Chaloner Hawke, in a road accident.

Hawke died in his beloved country house at Sunbury-on-Thames on 17 October 1781. He was buried near his wife and infant son William in the parish church of St Nicholas, North Stoneham. His heir was his eldest son, Martin Bladen Hawke.

Olivier Goossens

Leave a comment