“Now, God be praised, I will die in peace.”

These were the final words of James Wolfe, commander of the British forces who had just defeated the French army before the gates of Quebec in Canada. Despite being in excruciating pain, the general must also have felt a sense of relief. This battle marked the successful conclusion of a frustratingly long siege. Wolfe must have been well aware that this significant victory had secured him an honorable place in the annals of British military history. Once the news reached the shores of his homeland, the late general became known as “The Hero of Quebec,” “The Conqueror of Quebec,” or even more boldly: “The Conqueror of Canada.” The latter title was certainly no exaggeration: Quebec was the main stronghold of French North America, and its capture was tantamount to the conquest of all of Canada.

Historical Background

By 1759, the Seven Years’ War had already been raging for three years on the European continent. There, the British and the French once again found themselves pitted against each other as part of two opposing grand alliances. However, the fight between the French and the British can to some extent be regarded as a separate conflict. Their stakes were entirely different from those of the other European kingdoms. The French and the British were, in fact, primarily fighting over possession of the overseas colonies in North America and India. From the Thirteen Colonies (present-day USA), the armies of the British crown marched against French forces in what is now Canada.

In 1758, one column conducted a successful campaign against enemy forts along the present-day American-Canadian border. At the same time, British soldiers under Major General Jeffrey Amherst, in cooperation with the Royal Navy, managed to capture Louisbourg, situated at the eastern end of Cape Breton Island. This fortress lay at the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River and thus controlled access to Quebec and Montreal, the most important cities of New France.

The fall of this stronghold marked a major turning point in the struggle for Canada: the road to Quebec now lay open. Before advancing, however, the British had to wait out the harsh Canadian winter, during which the Saint Lawrence River typically freezes almost entirely

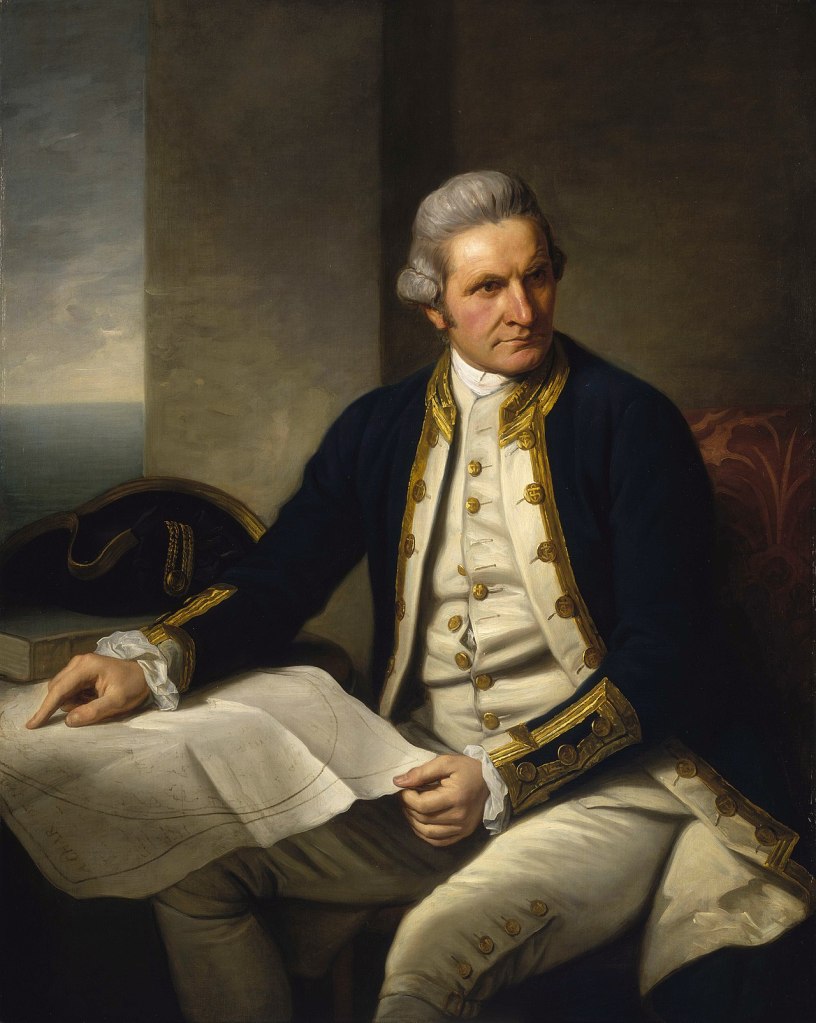

The British, however, did not remain idle during the winter months. A large expeditionary force was being prepared at Louisbourg for the decisive battle for Quebec. There was no need to bring in new troops from Europe since there were enough men available in North America. In total, about 7,700 soldiers would participate in the expedition. Major General James Wolfe, who had distinguished himself during the capture of Louisbourg by playing a pivotal role in its fall, was given command of the land forces. His experience with such amphibious operations would prove valuable: the plan was to strike Quebec from the Saint Lawrence River. A vast fleet was thus required to transport and protect such a large force. For this critical mission, the British could not afford to be frugal with their warships. For the operation, the Royal Navy placed 22 ships of the line under the command of Admiral Charles Saunders.

While the British army and navy prepared in Louisbourg during the winter of 1758–1759, Admiral Philip Durell was ordered to explore the Saint Lawrence River as far as Isle aux Coudres. The river was not only vast but also treacherous, riddled with dangerous shoals all the way to Quebec. Finding a safe passage before departure was therefore a matter of urgency. The peril of navigating the Saint Lawrence had been tragically demonstrated in 1711, when an expedition to Quebec ended in disaster: eight ships and 850 men were lost to shipwrecks.

“The river was not only vast but also treacherous, riddled with dangerous shoals all the way to Quebec.”

When Saunders arrived in Louisbourg at the end of April, he was dismayed to find that Durell had still not departed. The frustrated British naval commander promptly ordered him to set course for the river. To make up for lost time, Durell exceeded his original orders and managed to sail as far as Île d’Orléans. In other words, the British had safely reached Quebec’s doorstep.

The success of Durell’s mission owed much to the collaboration with local pilots and the expertise of none other than the future world-famous navigator and explorer, James Cook. Durell left buoys in his wake to mark the navigable route. Meanwhile, the invasion fleet and expeditionary army at Louisbourg were at full strength. All the pieces were in place—the chess game could begin.

Prelude to the Battle

On June 1st, Saunders and Wolfe set sail aboard HMS Neptune, leading the British expeditionary force bound for Quebec. Durell’s scouting squadron had done its job well: on June 27, the fleet arrived safely at Île d’Orléans. When the French commander at Quebec received the news, he must have been struck with disbelief. His name was General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, and he had been convinced that a fleet of such size would never dare approach the city. The French scrambled to man the defenses and ready the cannons in preparation for a siege.

The British first established their camp across from Quebec on Île d’Orléans. Shortly after their arrival, the besieged French attempted to strike the first blow. On the night of June 28, the waters of the Saint Lawrence were set ablaze: the French had launched several fire ships toward Saunders’ fleet. The attack, however, ended in failure when a nervous captain ignited his vessel prematurely. As a result, the British were alerted in time and able to take effective countermeasures. If nothing else, this event inspired one of the finest works in the oeuvre of the renowned maritime painter Samuel Scott (1702–1772).

“the British landing on July 31 ended in disaster”

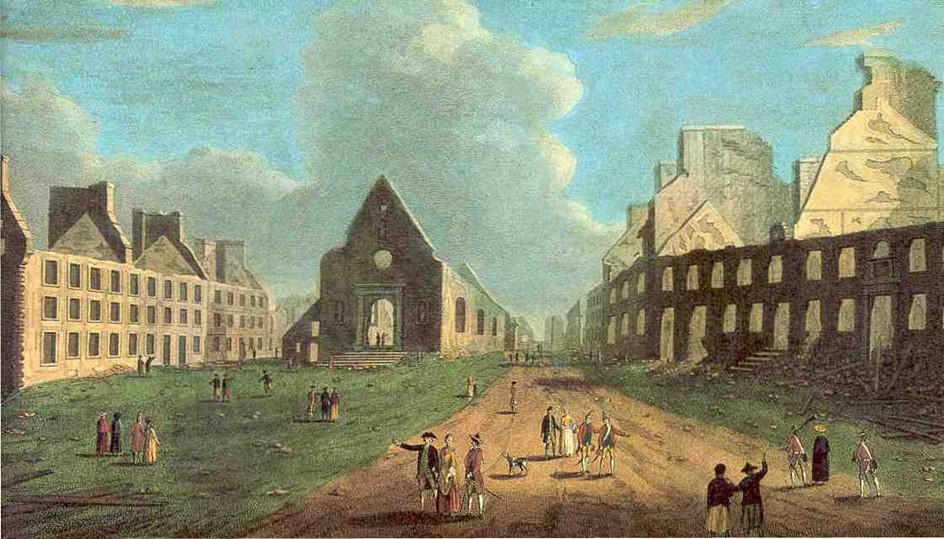

The failed fire ship attack—along with strong gusts of wind during the first nights—revealed the vulnerability of the British anchorage. Seeking a more sheltered position, Saunders moved the fleet to Point Lévis on the right bank. There, British troops established a battery directly opposite Quebec’s Lower Town, which they relentlessly bombarded until it was reduced to rubble. Meanwhile, Wolfe scouted for a suitable landing site from which to assault the French. He settled on Montmorency Falls, northeast of Quebec near the suburb of Beauport. Montcalm, however, had heavily fortified the area, and the British landing on July 31 ended in disaster.

Wolfe deployed his elite Louisbourg Grenadiers, but the assault on the French lines ended in failure. The grenadiers suffered heavy casualties and were forced to retreat. In the wake of this fiasco, some French officers grew confident that the British expedition was faltering, but Wolfe and his men were not so easily deterred. The British soon resumed their search for a suitable landing site on the left bank of the river.

The British command had already begun to consider the possibility of an operation upstream from Quebec at an early date. On July 18, Captain Rous successfully slipped past the French batteries with a few ships and secured a position on the Saint Lawrence southwest of the city.

Initially, Wolfe was hesitant to launch an attack west of Quebec. He feared that his forces could be quickly isolated and surrounded. But after the failed assault on July 31, disease began to spread through the British camp, morale plummeted, and doubts about Wolfe’s leadership intensified. He was under pressure to act—and quickly. By the end of August, Wolfe made up his mind: he would attempt a breakthrough upstream. One major advantage remained—the element of surprise.

“disease began to spread through the British camp, morale plummeted, and doubts about Wolfe’s leadership intensified. He was under pressure to act—and quickly”

Montcalm did not anticipate an attack via the route between Montreal and Quebec. The idea likely seemed even more improbable after he had stationed a sizable detachment under Louis de Bougainville near Cap Rouge. Confident in his ability to encircle any British landing west of the city, Montcalm remained convinced that Wolfe would make another attempt at Montmorency Falls.

Admiral Saunders played into French expectations by staging a diversion near Beauport, while Wolfe and his troops quietly moved upstream. The true landing site chosen by the British was Anse au-Foulon—a 53-meter-high cliff defended by only about a hundred men. Beyond the cliff stretched the Plains of Abraham, named after a 17th-century pilot and fisherman who had once been granted the land. This open expanse was ideal for deploying an army. Wolfe set the date for the assault: September 13.

The Battle

In the early hours of September 13, under cover of darkness, about 24 British soldiers silently rowed toward Anse au-Foulon. Colonel William Howe had been chosen to lead the detachment. His mission was critical: overcome the local defenses and clear the way for Wolfe’s army. The plan nearly unraveled when a French scout spotted the men during their climb—but one of Howe’s soldiers, fluent in French, managed to convince the sentry that they were a friendly supply unit.

Moments later, Howe and his men successfully drove off the small French guard force at Anse au-Foulon. His precise and daring execution did not go unnoticed. Howe would later rise to prominence, eventually serving as commander of British land forces during the early years of the American Revolutionary War, some two decades later.

Meanwhile, further east, Admiral Saunders had effectively diverted French attention with his feint. To lend credibility to the ruse, he placed sick and wounded soldiers in rowboats, creating the illusion of an imminent landing near Beauport.

Meanwhile, the Plains of Abraham began to fill with British troops, bracing for the inevitable French response. By 8:00 a.m., around 4,500 soldiers had landed. When a stunned Montcalm learned of the British presence behind his lines, he immediately rode out to confront them. Rather than wait for reinforcements, he chose to act swiftly, advancing with roughly 3,500 men.

When the French appeared on the plain, Wolfe’s forces had already formed a U-shaped line, two ranks deep. What followed happened quickly. The French fired first, but their volley was disorganized and largely ineffective. Many of Montcalm’s men were militia, better suited to forest skirmishes than pitched battle on open ground. Then came the British reply. Wolfe’s redcoats held their fire until the French were just 27 meters away—then unleashed a devastating, coordinated volley. Advancing slightly, they fired again, followed by a fierce bayonet charge.

“The well-timed volleys shattered the French line. Unable to withstand the pressure, Montcalm’s forces broke and fled.”

The well-timed volleys shattered the French line. Unable to withstand the pressure, Montcalm’s forces broke and fled. The British had won the day—but at a high price. General Wolfe had been struck by three musket balls during the battle, the last piercing his chest. It proved fatal. In his final moments, he was told that the French were retreating. Wolfe gave a few last orders, then lay back and said, “Now, God be praised, I will die in peace.” Moments later, he closed his eyes for the last time. Meanwhile, Bougainville’s reinforcements finally arrived on the field—but too late. Learning that Montcalm had been defeated and was in full retreat, Bougainville called off the attack.

Consequences of the Battle

The French, too, mourned the loss of their commander. Montcalm had been fatally wounded during the battle and died the following morning. Meanwhile, British Brigadier General George Townshend had taken over command and positioned his troops before the walls of Quebec.

The new French commander, Governor Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnial, judged the situation hopeless. He chose to evacuate Quebec with the bulk of his forces to join Bougainville. The city surrendered shortly afterward, and on September 18, the French commander Jean-Baptiste Nicolas Roch de Ramezay ordered the drums of surrender to be beaten.

The following year, the French launched a counteroffensive from Montreal in an attempt to retake Quebec. On April 28, 1760, they nearly succeeded, defeating the British at Sainte-Foy and driving them back toward the city. However, the ensuing siege faltered due to a shortage of artillery and ammunition. Quebec would never again fall into French hands.

“Quebec would never again fall into French hands.”

Meanwhile, the Royal Navy dealt a fatal blow to France’s ability to wage war overseas by destroying Louis XV’s fleet in European waters—first at Lagos, then at the Bay of Quiberon. With its sea lanes cut off, Paris could no longer supply its forces in North America. The French military presence withered, and in September 1760, the final stronghold—Montreal—fell to the British.

Three years later, in 1763, the French king signed the Treaty of Versailles, formally recognizing British sovereignty over Canada.

Olivier Goossens

Leave a comment