Historical Background

The Seven Years’ War is regarded by some historians as the first true world war. Although the intensity and bloodshed of the 20th-century conflicts could not be matched by any war of the 18th century, geographically speaking, this claim is not far from the truth. While many countries fielded vast armies against each other all over Europe, British and French colonial forces incessantly fought in the Americas and the Indian subcontinent. In North America, France upheld an ambitious claim to all land around the Great Lakes, the St. Lawrence River, the Mississippi, and its tributaries. Hunters and traders from the Thirteen Colonies nevertheless ventured into the western frontier despite French claims. This spelled conflict, and the two began fighting in 1754 in the so-called, unofficial “French and Indian War,” characterized by incessant skirmishes.

“Before Britain could march on Quebec (and Montreal), however, they first had to subdue the formidable stronghold of Louisbourg.”

To protect their claims, the French had built a powerful line of forts stretching from Montreal to Fort Duquesne in modern-day Pittsburgh. These fortresses were heavily dependent on Quebec and Montreal for their survival, which in turn relied on supplies and reinforcements from France. The French entrenched themselves even further in 1756 after Montcalm captured Fort Ontario and Oswego at the eastern end of Lake Ontario, and the following year subdued Fort William Henry at the southern end of Lake George, burning the English settlements along the Mohawk in the process. The British, meanwhile, fared less well in the North American theatre, with nearly all their expeditions against the French strongholds along the Great Lakes ending in disaster.

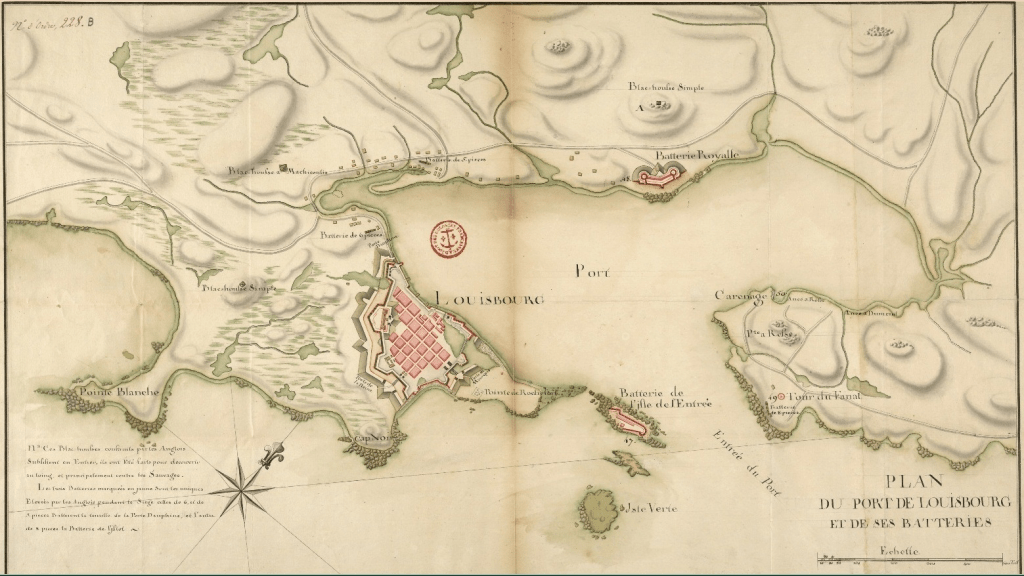

London changed its strategy. They decided to strike at the heart of French North America: Quebec. There were three possible routes—two overland and one via the St. Lawrence River. An amphibious operation via the latter proved most advantageous, as it enabled Britain to deliver a well-rested and supplied expeditionary force directly to the gates of Quebec. Before Britain could march on Quebec (and Montreal), however, they first had to subdue the formidable stronghold of Louisbourg.

Situated at the eastern end of Cape Breton Island—also known as Île Royale—this settlement controlled access to the St. Lawrence River. It was so well fortified that it was called the “Dunkirk of America.” Simultaneously, its deep natural harbour provided perfect shelter for a squadron capable of wreaking havoc on British shipping in the region.

“It was so well fortified that it was called the ‘Dunkirk of America.'”

Preparations

An initial attempt to capture Louisbourg was made in 1757 by a force of some 12,000 men under Lord Loudon, supported by a naval squadron of 15 ships of the line under Admiral Holburne. They were met, however, by foul weather and a formidable French force at the stronghold—9,000 men and 18 ships of the line. Loudon and Holburne therefore abandoned the mission and returned to their base at Halifax.

Another attempt was to be made the following year with the full backing of First Lord of the Admiralty George Anson and Britain’s political leader, William Pitt the Elder. They identified Louisbourg as an absolute priority in the war. Lord Loudon was replaced by the astute Major General Jeffery Amherst, a personal choice of Pitt, and Holburne was superseded by Admiral Edward Boscawen. Amherst’s brigadiers were Charles Lawrence, James Wolfe, and Edward Whitmore.

The expeditionary force was to be assembled at Halifax, the capital of Nova Scotia. Halifax possessed a large natural anchorage perfect for harbouring the numerous vessels required to support the campaign. Troops and ships were subsequently summoned from England, Ireland, Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. Before the fleet reached full strength, a sizeable forward force of seven ships of the line under Sir Charles Hardy had already gathered at Halifax before the winter of 1757–58 made further operations impossible. Hardy’s mission was to set out as soon as the harsh winter weather relented and to establish an early blockade of Louisbourg until the main force arrived.

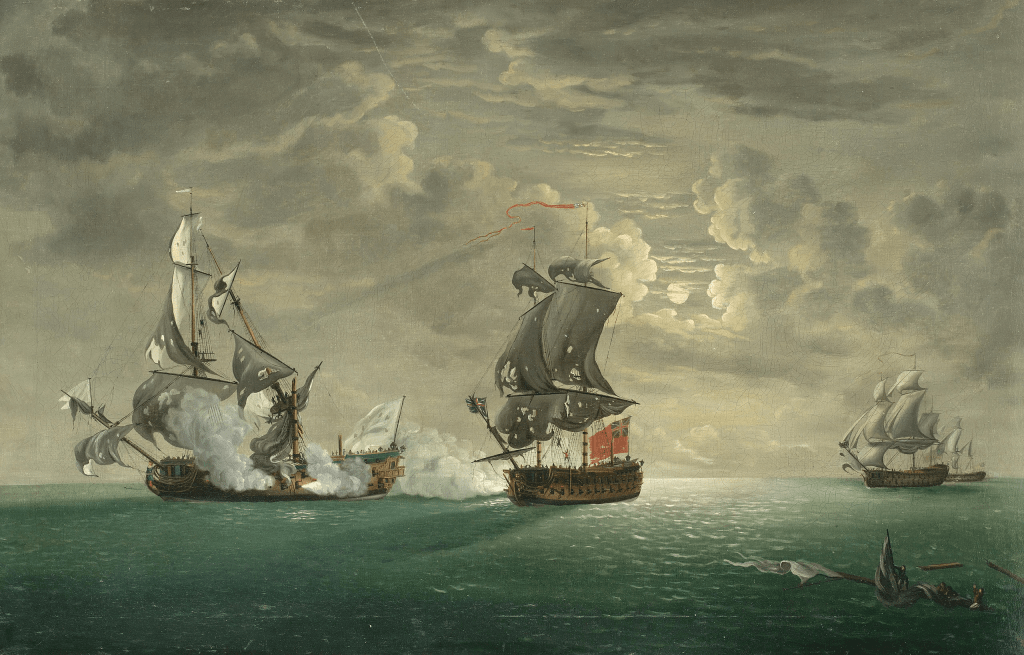

Meanwhile, back in Europe, the British had secured an important strategic victory that bolstered their position in North America. The French were preparing to reinforce the St. Lawrence stronghold with 15 ships under Admiral Jean-François de La Clue-Sabran at Toulon. Admiral Henry Osborne, however, threw a spanner in the works. After a storm forced La Clue to take shelter in Cartagena, Osborne positioned his squadron off the harbour to keep the enemy bottled up. He received word that three more ships of the line under Admiral Michel de Menneville had left Toulon to reinforce La Clue. On 28 February, Osborne engaged the approaching ships, which were completely taken by surprise. Two vessels—among them the famous Foudroyant—were captured, and the third was purposely run aground. Osborne then resumed his blockade of La Clue at Cartagena, who remained unable to assist Louisbourg. The stronghold at the mouth of the St. Lawrence was left to fend for itself.

Preparation of the expeditionary force faced no significant opposition, as the French were too preoccupied with reinforcing Louisbourg and Quebec with what little they had. By spring, some 11,500 men had gathered at Halifax for the attack. Most were regulars, with the exception of four companies of American Rangers. The three brigadiers were each given one division: Red under James Wolfe, Blue under Charles Lawrence, and White under Edward Whitmore. As the soldiers awaited the ships to take them to their destination, much time was spent training and preparing for the complex mission ahead. Amphibious operations were, in fact, rare undertakings in those days. By May, everything was ready. The land force was supported by a squadron under Boscawen consisting of 21 ships of the line, two 50-gun ships, and numerous frigates and smaller vessels. Including transports, the fleet totalled 157 ships. Amherst’s force sailed out in late May.

The Battle

The fleet arrived in Gabarus Bay, three miles (4.8 km) from Louisbourg, on 2 June. The British were faced by a defending force of 2,500 regulars, 500 militia, and 2,500 sailors from a squadron of five warships, totalling 544 guns, anchored in the harbour. French firepower was supplemented by 219 cannons and 17 mortars installed on the battlements of Louisbourg. Overall command fell to Chevalier Drucour, a nobleman in his fifties who had served as governor of Île Royale for several years. Drucour had a long and distinguished naval career, having joined the French navy at age 16 in 1719. He must have known the English well, having spent a year as a prisoner of war after his ship, Mars, was taken by HMS Nottingham in October 1746. He prepared the defences as best he could, building entrenchments and gun emplacements along the shores of Gabarus Bay, manned by 2,000 men. His five ships of the line were meanwhile positioned to protect the harbour.

“During the retreat, though, several ships with light infantry drifted eastward and identified a safe landing spot protected by rocks”

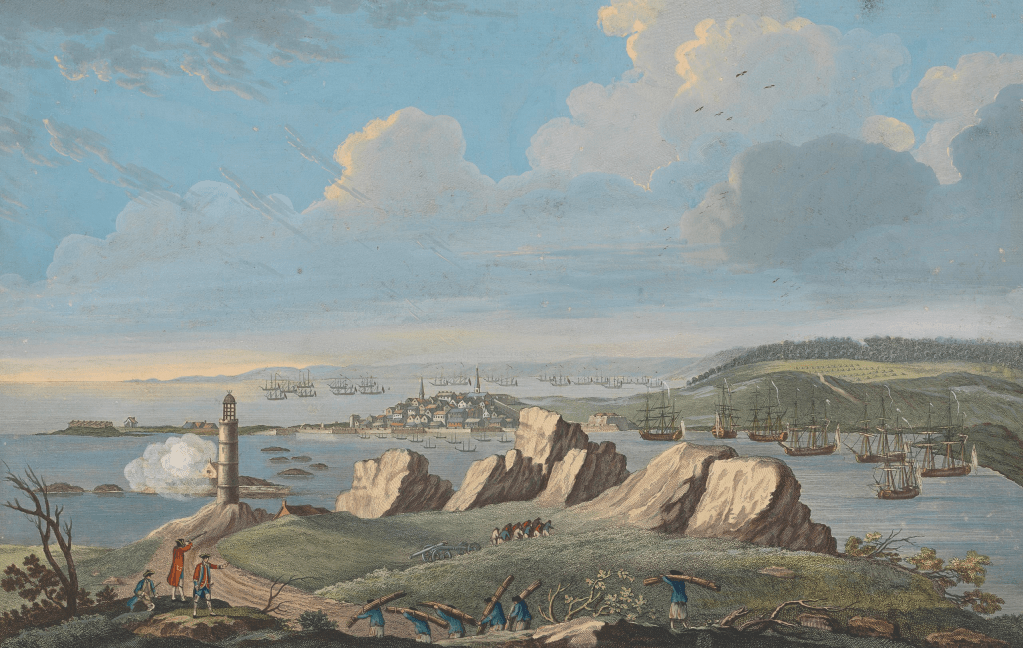

Adverse weather initially prevented the British from landing, but finally, on 8 June, troops under Brigadier General James Wolfe launched an assault under the protection of Boscawen’s cannons. Wolfe was aided by Lawrence and Whitmore, who staged feint attacks at White Point and Flat Point to the west. Drucour’s defensive measures paid off, however, and Wolfe’s attack was repelled. During the retreat, though, several ships with light infantry drifted eastward and identified a safe landing spot protected by rocks at Kennington Cove. Taking the initiative, they landed and secured the sandy beach, allowing the remainder of Wolfe’s men to follow. British soldiers swiftly capitalized on their position and attacked the French entrenchments from the flank and rear. Drucour was forced to retreat to Louisbourg. With the surrounding terrain secured, Amherst’s full force landed and established a perimeter around the stronghold.

The French position became more precarious when Wolfe captured Lighthouse Point. After marching some 7.5 miles (12 km) around the harbour, Wolfe reached the strategic location on 12 June with around 1,220 men. The capture enabled him to install a battery with a clear view of the harbour and town. The British bombardment began on 19 June. In the days that followed, the French guns fell silent one by one as the walls crumbled.

The End of the French Squadron and the Fall of Louisbourg

On 21 July, disaster struck when a British mortar shell ignited the French Célèbre, which caught fire. Strong winds spread the flames to Le Capricieux and L’Entreprenant. Drucour was left with only two ships.

The situation worsened further when the King’s Bastion—one of the largest buildings in North America—was struck and burned. Soon after, the Queen’s Bastion was also incinerated. French morale plummeted amidst the devastation.

On 25 July, the last two French ships were neutralized. A cutting-out party captured the Bienfaisant, piloting her out of the harbour, while the Prudent was set ablaze and sank.

“French morale plummeted amidst the devastation.”

Recognizing that further resistance was futile, Drucour struck his colours the next day. The French lost 102 men and had 303 wounded. Amherst’s forces suffered 172 killed and 355 wounded. King Louis XV also had to accept the loss of five warships, one of which was captured. The British demolished Louisbourg’s defences to prevent its reuse if it reverted to the French after a peace treaty.

The strategic value of the victory was monumental. The road to Quebec and Montreal now lay open.

Olivier Goossens

Leave a comment