Britain had been entertaining the idea of converting its submarine fleet into a nuclear-powered force since 1946. The first British designs for nuclear propulsion featured bulky, impractical gas-cooled reactors, similar to those used in the contemporary civilian nuclear sector. Work was suspended indefinitely in October 1952 so the Admiralty could invest its limited resources into other projects deemed more urgent. Meanwhile, their American allies across the Atlantic were already in the advanced stages of designing a practical nuclear reactor featuring a water-cooling system. This led to the construction of USS Nautilus, the world’s first nuclear-powered submarine, commissioned in September 1954.

During exercises with the experienced ASW units of the Royal Navy, Nautilus quickly convinced the First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Mountbatten, and Flag Officer Submarines Sir Wilfred Woods of the superiority of a nuclear-powered submarine. Such submarines were far more difficult to detect than noisy conventional diesel-powered units. Furthermore, a nuclear powerplant meant that, in theory, the submarine could remain submerged indefinitely, only surfacing to take in food and drink for the crew. Lord Mountbatten therefore decided to resume the development of a nuclear-powered submarine. The British realized, however, that assistance from the experienced Americans would be crucial to delivering an operable unit within a reasonable timeframe. Mountbatten, who was on good terms with the American Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Arleigh Burke, lobbied the United States for help. Some within the US Navy, such as Rear Admiral Hyman Rickover—head of the American naval nuclear power program—were reluctant to share such high-end technology. Rickover even refused to allow Mountbatten a visit aboard USS Nautilus. However, following a visit to Britain in 1956, Rickover finally relented and dropped his opposition.

“The British realized, however, that assistance from the experienced Americans would be crucial to delivering an operable unit within a reasonable timeframe.”

With the successful launch of Sputnik 1 by the Soviets, the Americans became deeply concerned about Russia’s staggering technological advancements. The fear of a superior adversary prompted Washington to abandon its technological protectionism toward the British. They figured that sharing technology with their most trusted ally would significantly bolster their odds in a potential war against the communist bloc. Finally, in 1958, the US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement was signed, giving the green light to transfer naval nuclear knowledge and an entire powerplant to the island nation. In return, the British would share their insights on submarine design and noise-reduction techniques. The Americans initially offered to supply a third-generation S3W reactor, but Mountbatten successfully negotiated an upgrade to the more sophisticated fifth-generation S5W pressurized water reactor, fitted aboard the Skipjack-class submarines. The US Navy also shared vital performance data from their early nuclear submarines—information that would prove invaluable when British designers began drawing the lines of Dreadnought.

Procuring the powerplant was a lengthy process, beginning with prototype testing at a special US facility. Many personnel from Vickers, Rolls Royce, and the Admiralty traveled across the Atlantic to learn more about nuclear technology. Once trained, they returned to the UK with the necessary reactor to get Dreadnought going.

The British, of course, had to handle the actual construction of the boat. The firm Vickers Armstrongs at Barrow-in-Furness was employed as the main contractor. During Dreadnought’s construction, Rolls Royce constructed a completely new British nuclear propulsion system in collaboration with the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority at the Admiralty Research Station, HMS Vulcan, at Dounreay, for the UK’s second nuclear-powered submarine, HMS Valiant.

The name Dreadnought was a symbolic choice. It had a proud legacy in the Royal Navy, having previously graced several groundbreaking vessels—most famously the revolutionary steam-turbine-powered battleship Dreadnought, launched in 1906. Once again, Dreadnought would represent a major leap forward in British naval history. The UK’s first nuclear submarine was laid down on 12 June 1959 and launched on Trafalgar Day, 21 October 1960, by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II (r. 1952–2022). She was commissioned into the navy on 17 April 1963.

“The name Dreadnought was a symbolic choice. It had a proud legacy in the Royal Navy, having previously graced several groundbreaking vessels.”

The 3,500-ton vessel was relatively small at 265.7 ft (81.0 m)—an acceptable compromise to meet deadlines. In fact, Dreadnought was completed on time and within budget. She had a beam of 31.2 ft (9.5 m) and a draught of 25.9 ft (7.9 m), and required a crew of approximately 113 men. Her armament included six bow tubes designed for the reliable 21-inch Mark 8 Mod 4 torpedoes, of which she carried 24. These torpedoes had a range of 5,000 yards at 45 knots. Her S5W nuclear reactor, placed amidships for stability, was connected to two English Electric steam geared turbines installed at the rear of the vessel, driving a single shaft. The entire powerplant was rated at 15,000 hp, allowing a top submerged speed of 28 knots. Forward of the turbines and reactor was the command centre and crew quarters. As a nuclear submarine built for long deployments, special attention was paid to improving crew living conditions. The enlarged accommodations made Dreadnought a popular posting among submariners, offering a welcome change from the typically harsh conditions on submarines.

“The enlarged accommodations made Dreadnought a popular posting among submariners, offering a welcome change from the typically harsh conditions on submarines.”

Once commissioned, Dreadnought spearheaded the UK’s Submarine Service for years to come. Most of her operations remain classified, making it difficult to gain a full picture of her service. However, she immediately began rigorous training to familiarize the crew with the revolutionary technology. Dreadnought visited Norfolk (US), Bermuda, Rotterdam, and Kiel for Kiel Week—where, as Europe’s first nuclear-powered submarine, she attracted many visitors. In October, she conducted exercises with Canadian and American forces north of Scotland. During these exercises, she experienced her first taste of Cold War tension, being shadowed by three Soviet ships and three submarines.

Several years later, on 19 September 1967, she made history with a high-speed voyage from Rosyth to Singapore, spending a staggering 26,545 miles submerged—proving exactly why she was built.

Earlier that same year, in June, Dreadnought used her torpedoes against a real target during a peacetime operation. The German tanker Essberger Chemist had wrecked south of the Azores. Though the crew had abandoned the ship, it continued to drift near busy shipping routes, posing a hazard. With her crew called back from leave in Gibraltar, Dreadnought rushed to the scene and fired torpedoes to sink the derelict vessel. Three torpedoes hit the mark, though final credit for the sinking went to the gunners of HMS Salisbury.

Some incredible footage of the event has come down to us…

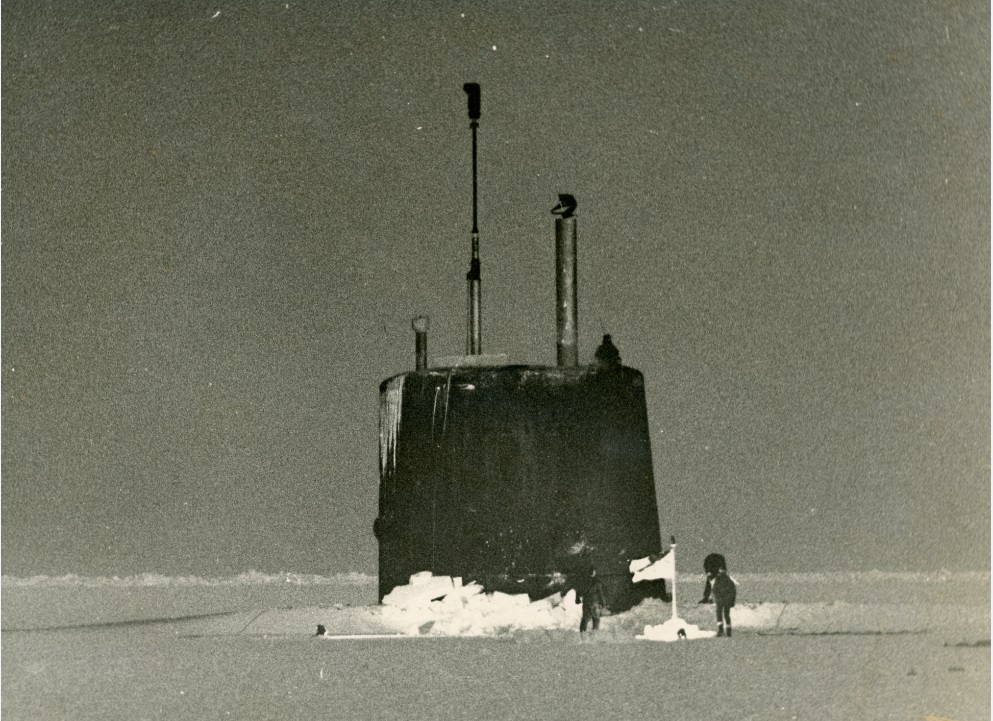

After seven years in service, Dreadnought underwent her first and only major overhaul at Rosyth. Minor hull cracking was addressed, her nuclear core was refuelled, and the ballast tank valves were replaced with quieter models. The refit was completed on 10 September 1970, after which the famed silent hunter returned to active duty. She scored another milestone on 3 March 1971 by becoming Britain’s first submarine to surface at the North Pole. Damage to her fin, bow, and propellers—caused by the ice—was discovered after the mission.

“She scored another milestone on 3 March 1971 by becoming Britain’s first submarine to surface at the North Pole.”

She continued her routine fleet exercises, and in November 1977 was scheduled to visit Australia. The trip was cancelled due to rising tensions with Argentina over the Falklands. Instead, she was deployed to the South Atlantic as part of Operation Journeyman, aimed at deterring Argentine aggression. Dreadnought covertly surveyed the Argentine coast—her last major deployment before being decommissioned in 1980 due to aging and the lack of proper nuclear fleet submarine facilities.

As part of the UK’s Submarine Dismantling Project (SDP), Dreadnought has remained afloat at Rosyth. Though her nuclear fuel has been removed, her interior is still intact. With her future uncertain, hopes remain high that she will one day be preserved as a museum ship.

Olivier Goossens

Leave a comment