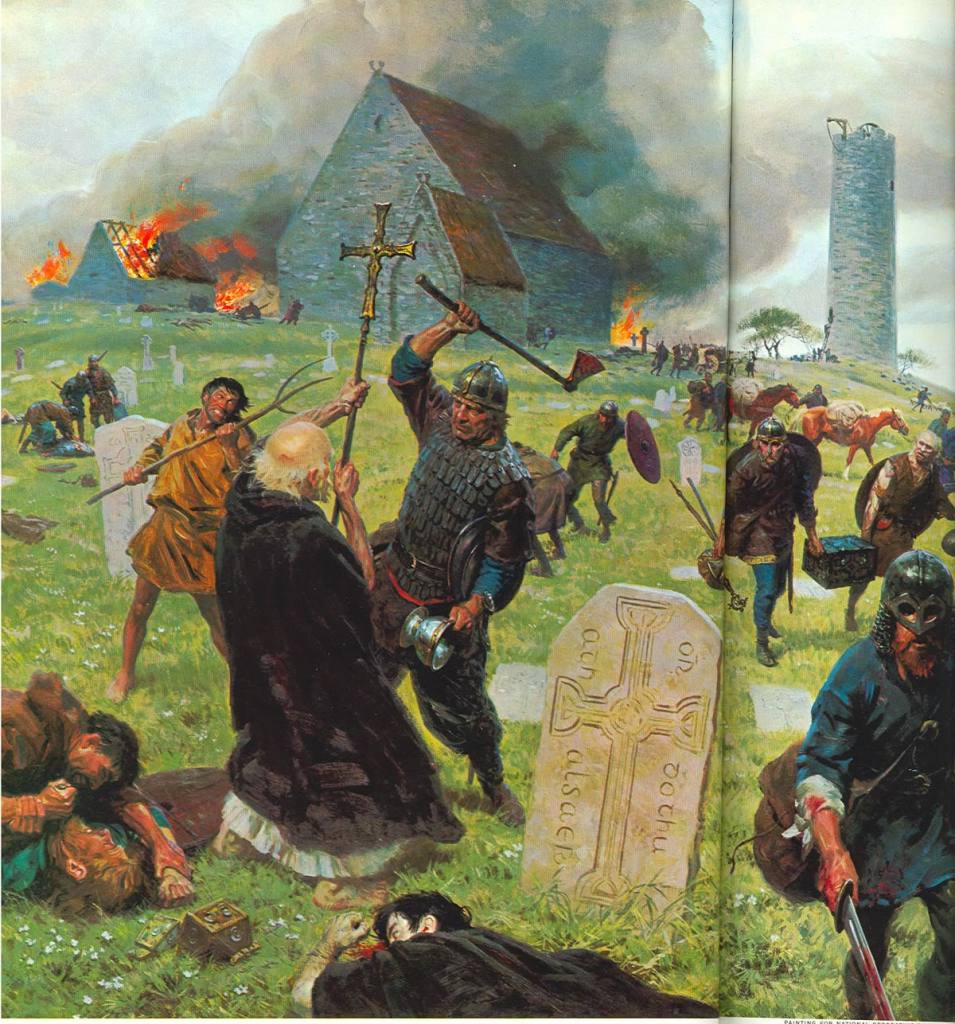

Surrounded by over 11,060 miles (17,800 km) of mainland coastline, England was both blessed and cursed by its surrounding waters. Its inhabitants learned early to maximize the blessings of the waves that wrapped around the island, from simple fishing vessels to early commercial cog trading ships. But so did its earliest aggressors. Notwithstanding the ancient invasion and occupation by the Romans of Britain in 43 CE, nor the hundreds of years afterwards, as there is little in the form of any discernible evidence of Roman efforts to repel the sea-borne attacks of the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, it would be the persistent attacks of the Danes in the ninth century that would force a rethinking of the protection of the island.

“It would be the persistent attacks of the Danes in the ninth century that would force a rethinking of the protection of the island.”

By the mid 800s, Britain had been consistently and pervasively ravaged by Viking attacks. Seemingly able to strike at will from nearly any direction, the early island kingdoms had been wholly ineffective in preventing these incursions, though sporadic efforts had been made to engage them at sea. The result was a despoiled and impoverished land with a dejected population that needed a new approach to confronting the haunting attacks of the Scandinavian raiders. They would find this in a new king in 871.

Alfred the Great (c. 848-899) had literally been raised fighting the Viking invaders of the British Isles. The fifth son of Aethelwulf, king of the West Saxons, Alfred had experienced the raider attacks for years, which had only been increasing in intensity since the 790s. The Vikings, with their shallow draft longships, would persistently raid the coastlines, while deploying mobile strike forces into the countryside. Their footprint in the country began taking hold with the capture of York in 866 as well as subsequent victories over the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of East Anglia and Mercia.

“Alfred the Great (c. 848-899) had literally been raised fighting the Viking invaders of the British Isles.”

The invaders were finally checked by Alfred at the Battle of Ashdown in 871, preserving the kingdom of Wessex and effectively buying time for both Alfred and a burgeoning sense of statehood to develop—ultimately leading to the creation of England. The effectiveness of the Viking longships was not lost on Alfred who was a keen observer of the world around him. The king recognized that he and his realm stood a much better chance of deterring their enemies by engaging them at sea, before they could make landfall where he was typically at a disadvantage, and to do that, he would need ships.

“Alfred, by 897, having discovered that ‘the first and only real line of defence for an island consists in an efficient navy,’ set about creating his own ships for the protection of the realm.”

It is this decision and awareness by Alfred that Britain’s future security—be it economically, politically, and/or militarily—would come to hinge on the strength of the island’s naval forces. There have been claims by some historians that this is why Alfred the Great should be credited with creating Britain’s first official navy, while others point to a Tudor king several hundred years later. Wherever one falls on the debate, what can be said is that Alfred’s strategic wherewithal in understanding the threat, and then taking steps to counter that threat, showed a keen understanding of the necessity for a force of ships to challenge and beat their enemies at sea. This legacy is what would serve as the underlying kindling for the creation of the future and powerful Royal Navy.

Alfred, by 897, having discovered that ‘the first and only real line of defence for an island consists in an efficient navy,’ set about creating his own ships for the protection of the realm.1 He did not want to simply copy those of his enemies, but to fashion ships that were distinctly suited to his needs, thus becoming the progenitors of the royal fleet. These ships, built to combat rampant piracy by the Vikings from their base of operations in Northumbria, were purposefully made larger than those of the Vikings. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that:

“King Alfred had long ships built to oppose the [Danish] warships [lang scipu ongen oa aescas]. They were almost twice as long as the others. Some had sixty oars, some more; and they were both swifter and steadier, and also higher than the others. They were not shaped either after the Frisian or the Danish model, but so as he [King Alfred] himself thought that they might be most serviceable.”2

The king was a skilled man in both carpentry and seafaring, so it is completely plausible—and likely—that he played a direct role in the construction of his new fleet. What is far less certain is the matter of Frisian and Danish patterns. At the time, and based on the circumstances, it can be assumed that the mention of Danish ships refers to their construction as ships of war, while the reference to Frisian ships is vaguer. A strong assumption can be made regarding Frisian vessels: due to their nature as merchant ships, they likely featured a deep draft and high freeboard (the distance between the waterline and the deck). The construction of these large vessels—using only the finest materials, as the king insisted—came at an enormous cost in both financial resources and manpower. Alfred further demanded that the crews of these ships be rigorously trained and well-outfitted to combat their aggressors. As for these aggressors, the king commanded that no quarter be given, with prisoners ‘ordered to be hanged.’3

This early naval policy of defensive offense would be Alfred’s greatest contribution to the evolution and eventual creation of a supreme Royal Navy. As an island nation, Britain—with its limited manpower yet high susceptibility to naval incursions and invasions—had to turn the surrounding waters to its advantage. A well-trained and outfitted naval force was therefore recognized by Alfred as essential, enabling him and future monarchs to engage and defeat enemies before they could make landfall, while also protecting the kingdom’s vital commercial ports. This policy, when paired with Alfred’s small yet effective fleet, allowed his forces to engage and defeat several much larger Viking fleets, capturing many ships and putting their enemies to the sword.

“As an island nation, Britain—with its limited manpower yet high susceptibility to naval incursions and invasions—had to turn the surrounding waters to its advantage.”

Alfred’s actions and foresight began to show both his subjects and other peoples of the island the value of a strong maritime force. Command of the sea would become necessary for any ruler of the island to maintain power, for who would follow a king who could not protect his people or their livelihood? More than just a royal dictate to control the waterways, a powerful naval force—and the value placed upon it—began to embed itself in the psyche of the English people. In the centuries to come, the English nation and its society would grow increasingly synonymous with naval supremacy.

Following Alfred’s death in 899, his son Edward the Elder (874–924) ascended the throne and continued prosecuting campaigns against their enemies, aided by his martially skilled sister, Æthelflæd, “Lady of the Mercians” (c. 870–918). Edward had long taken part in battles against the Vikings, notably at the Battle of Farnham in 893, where he led an Anglo-Saxon force to victory over a marauding Viking host, capturing gold and loot while killing or driving off many. These victories, however, were not conclusive in eliminating the Viking threat, as they continued to dominate the north in Northumbria, the Danelaw (East Anglia and the East Midlands), along with the Britons of Strathclyde and assorted Welsh princes.”4

The Danes broke the tentative truce with Edward in 910 when their army plundered the land of the Mercians. In response, “the king had gathered together about a hundred ships, and was then in Kent while the ships were sailing along sea by the south-east to meet him. The army therefore supposed that the greatest part of his force was in the ships, and that they might go, without being attacked, where that ever they would.” The result was the destruction of the Viking army, as Edward “slew many thousands” of them.5

What we can infer from this is the importance Edward placed—at enormous expense—on naval operations: acquiring, equipping, and manning such a large fleet was no small feat. In many respects, Edward was one of England’s first admirals, assembling a considerable fleet and carefully coordinating its movements with land forces to decisively engage and destroy the enemy.

Edward’s successors would leverage sea power to varying degrees of success. His son and successor, Æthelstan (c. 894–939), participated in two notable events that reflected the growing importance of sea power and its consequences. The first occurred in 934, when the king led both a “land-force and a naval armament” into Scotland and along its eastern coast, where he “laid waste a great part of it.”6 This projection of power demonstrated a coordinated effort between land and sea forces, echoing the model set by his father. The naval component made deep incursions into Scotland possible—especially significant given the craggy, undeveloped nature of roads and trails, which made overland supply and communication difficult. The ships reportedly continued up past Aberdeenshire to Caithness, a feat that would have required sturdy vessels and skilled crews. Once again, we see evidence of a growing culture of seamanship—military seamanship at that.

The second event came just three years later, in 937, at the Battle of Brunanburh (the exact location of which remains debated). It was here that Æthelstan and his half-brother Edmund (c. 920–946) confronted a large host of Vikings and Scots who had arrived by sea—some sources claiming they came in 615 ships—and defeated them decisively on land. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle does not clearly specify the origins of these “hardy Scots” and “northmen [that] sail’d in their nailed ships,” though references to Dublin and Ireland offer some clues.7 What is clear, however, are the consequences of the battle.

First and foremost was Æthelstan’s consolidation of his power, particularly as overlord of the Welsh. He also pursued dynastic diplomacy, marrying off his daughters to various European kings and nobles. English ships played a vital role in this effort, supporting diplomatic missions and helping restore displaced monarchs to their thrones—such as Louis IV of the Franks and Duke Richard of Brittany.8 Additionally, Æthelstan’s rising prestige drew recognition from abroad: the Norwegian king Harald Fairhair (c. 850–932) sent his son to the English court, seeking to gain favor and remain in Æthelstan’s good graces.

This early naval power had proven its value—not only in gaining a kingdom, but more importantly, in maintaining one. Æthelstan and his predecessors were capable of building and launching fleets to confront threats both domestic and foreign. However, the military effectiveness of these fleets remained limited due to a lack of formal administrative structure. The first real steps toward correcting this would come under the reign of King Edgar (r. 959–975).

“This early naval power had proven its value—not only in gaining a kingdom, but more importantly, in maintaining one.”

Edgar—known as “the Peaceful” due to the relative stability and prosperity of his reign—enacted government reforms that tied the strength of the navy more directly to royal authority. These reforms extended into monastic and ecclesiastical circles, increasing the king’s power through his appointed bishops and abbots. Among these innovations was the creation of an administrative institution known as the ship-soke.9

Though historical details of the ship-soke remain somewhat obscure, it appears to have established a system of obligatory naval service. Initially drawing on ecclesiastical resources, the system was organized into units called “hundreds.” According to N.A.M. Rodger, a hundred was “a subdivision of the county for purposes of taxation and military service, in principle an area of one hundred ‘hides,’ each hide being enough land to support one household.”10

Under the ship-soke system, every three hundreds were required to provide one ship and its full crew. This responsibility fell to the local landowner, who was obligated to supply both the vessel and sixty men to crew her. These men served either on land or at sea and were led by the same appointed officer in both roles. This organizational development is a clear indication of the importance Edgar placed on maintaining a ready and responsive naval force—one better equipped to meet threats than in previous generations. Equally important was the symbolic and strategic projection of royal power that such a fleet represented.

Edgar put on such a display in the northwestern town of Chester. Situated on the estuary of the River Dee, which empties into the Irish Sea, Chester had long been a symbol of power, having once served as the headquarters of Roman Legion XX in the 5th century—then known as Deva or Castra Devana. The king was acutely aware of the city’s historic weight, and in 973, with the presence of his sciphere (naval forces), he was paid homage by his dependent kings.11 While documentation on the size of Edgar’s navy is highly suspect—with some sources exaggerating that it numbered between “four and five thousand sail,” a figure unlikely given the resource and manpower demands—the event nonetheless demonstrated Edgar’s formidable authority.

The number of rulers who recognized Edgar’s overlordship ranged from six to eight. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records six, though it likely omitted two due to their “sub-regal” status. Regardless of the precise number, their collective presence and submission testified to the strength Edgar wielded.12 His martial might, both naval and terrestrial, was later praised in verse:

“No fleet was so daring,

nor army so strong,

that ‘mid the English nation

took from him aught,

the while that the noble king

ruled on his throne.”13

Under Edgar, the union of naval power with royal authority reached a height previously unseen in the British Isles. His semi-structured naval administration enabled him to summon and maintain a sizeable fleet, laying the foundation for a regular sea power. Edgar made deliberate use of this capacity, reportedly dispatching his fleet annually to circumnavigate the British Isles—a show of strength no subordinate ruler could hope to match.

This assertion of English naval supremacy was further underscored by a highly symbolic ceremony. Not long after his coronation, Edgar was rowed up the River Dee by subject rulers from North and South Wales, the Isle of Man, the Hebrides, Strathclyde, and Galloway—while Edgar himself took the helm as steersman.14 The significance of this act was twofold. First, by holding the steersman’s position, Edgar symbolically commanded the entire vessel—asserting his role as captain, and thus overlord. Second, by physically rowing him, these regional kings acknowledged his supremacy and, crucially, the might of his naval power.

Years later, chroniclers would remark, “He held the land as an emperor… He alone ruled over the kings, and over the Scots and the Welsh. Never since Arthur had any king such power.”15

“However, the strength of this naval force was tied intimately to the strength of its ruler.”

However, the strength of this naval force was tied intimately to the strength of its ruler. After Edgar’s death in 975, the fortunes of English sea power would fluctuate dramatically, waxing and waning through unstable reigns and intermittent threats, until its firm consolidation centuries later under the shipbuilding programs and sea power initiatives of Henry VII (1457–1509).

Michael G. Stroud

Michael G. Stroud is a military historian and adjunct professor of history at Cornerstone University.

Bibliography

- Allen, Joseph. Battles of the British Navy. I. Vol. I. 2 vols. London, UK: Henry G. Bohn, 1852.

- Alsop, J.D. “A Regime at Sea: The Navy and the 1553 Succession Crisis.” Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies 24, no. 4 (Winter 1992): 577-590. https://doi.org/10.2307/4050667.

- Bacon, Francis. “Bacon’s History of the Reign of King Henry VII.” Edited by J. Rawson Lumby. HathiTrust. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=loc.ark%3A%2F13960%2Ft4kk9sw4j&view=1up&seq=1&skin=2021.

- Bennett, Matthew. Fighting Techniques Of The Medieval World AD 500 – AD 1500: Equipment, Combat Skills, and Tactics. New York, NY: Thomas Dunne Books, 2006.

- Borough, Sir John. The Sovereignty of the British Seas…written in the Year 1633, 1651.

- Chaucer, Geoffrey. “Canterbury Tales.” Edited by Larry D Benson. Harvard’s Geoffrey Chaucer Website. Harvard University. Accessed August 24, 2022. https://chaucer.fas.harvard.edu/pages/text-and-translations.

- Childs, David. “Shock and Oar: Mary Rose and the Fear of French Galleys.” History Today 57, no. 4 (April 2007): 41-47. https://www.proquest.com/magazines/shock-oar-mary-rose-fear-french-galleys/docview/202822074/se-2.

- Childs, David. Tudor Sea Power: The Foundation of Greatness. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Pub., 2009.

- Clowes, W. Laird. The Navy of Henry VIII & Elizabeth I: English Naval Warfare, Exploration & Vessels during the 16th Century. Driffield, UK: Leonaur, 2017.

- Clowes, William Laird. The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to 1900. I. Vol. I. 7 vols. London, UK: Chatham Pub., 1996.

- Corbett, Julian S. Drake and the Tudor Navy with a History of the Rise of England as a Maritime Power. II. Vol. II. 2 vols. Elibron Classics. London, UK: Adamant Media, 2007.

- Corbett, Julian Stafford. Drake and the Tudor Navy: With a History of the Rise of England as a Maritime Power. 1. Vol. 1. 2 vols. London, UK: Wentworth Press, 2010.

- Corbett, Julian S., ed. Papers Relating to the Navy during the Spanish War 1585-1587. 11. Vol. 11. Navy Record Society, 1898.

- Davies, C.S.L. “The Administration of the Royal Navy under Henry VIII: The Origins of the Navy Board.” The English Historical Review 80, no. 315 (April 1965): 268-288. https://www.jstor.org/stable/560133.

- Deputy Keeper of Records. “Calendar of the Patent Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office / 1563-1566.” HathiTrust.Accessed August 14, 2022. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951d02046630o&view=1up&seq=5&skin=2021.

- Doran, Susan. The Tudor Chronicles, 1485-1603. New York, NY: Metro Books, 2009.

- Glasgow, Tom. “The Navy in the French Wars of Mary and Elizabeth I: Part III. The Navy in the Le Havre Expedition, 1562-1564.” Mariner’s Mirror 54, no. 3 (1968): 281-296. https://doi-org.ezproxy2.apus.edu/10.1080/00253359.1968.10659447.

- Goldingham, C.S. “The Navy Under Henry VII.” The English Historical Review 33 no. 132 (October 1918): 472-488. https://www.jstor.org/stable/550919.

- Grove, Eric. Great Battles of the Royal Navy: As Commemorated in the Gunroom, Britannia Royal Naval College, Dartmouth. London, UK: Bramley Books, 1998.

- Grummitt, D. “The Defence of Calais and the Development of Gunpowder Weaponry in England in the Late Fifteenth Century.” War in History 7, no. 3 (2000): 253-72. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/defence-calais-development-gunpowder-weaponry/docview/224146890/se-2.

- Guy, John Alexander. Tudor England. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Hallam, Elizabeth, ed. The Chronicles of the Wars of the Roses. London, UK: Guild Publishing, 1988.

- Herman, Arthur. To Rule the Waves: How the British Navy Shaped the Modern World. New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 2009.

- Hill, J. R., and Bryan Ranft, eds. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Royal Navy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Ingram, James Henry, trans. “The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.” Project Gutenberg, August 1, 2008. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/657/pg657.html.

- Kemp, Peter, ed. History of The Royal Navy. London, UK: Arthur Bark Limited, 1969.

- Knighton, C.S., and Loades, David. Elizabethan Naval Administration. Farnham: Taylor & Francis Group, 2013. Accessed August 14, 2022. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/apus/detail.action?docID=1389021.

- Konstam, Angus. Tudor Warships (2). Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2008.

- Loades, David Michael. The Tudor Navy: An Administrative, Political, and Military History. Aldershot, UK: Scolar, 1992.

- Loades, David. Englands Maritime Empire: Seapower, Commerce and Policy, 1490-1690. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education, 2000.

- Loades, David. Fighting Tudors. Surrey, UK: The National Archives, 2009.

- Lyte, H.C. “Calendar of the Patent Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry VII, 1485-1509 / Prepared under the Superintendence of the Deputy Keeper of the … V.1.” HathiTrust, 2020. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.31158008812835&view=1up&seq=53&skin=2021&q1=ship.

- M., Rodger N A. The Safeguard of the Sea: A Naval History of Britain, 660-1649. New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 1999.

- Marcus, G. J. A Naval History of England. the Formative Centuries. Boston, MA: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1961.

- Molyneaux, George. “Why Were Some Tenth-Century English Kings Presented As Rulers of Britain?” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 21 (December, 2011): 59-91, ProQuest.

- Moberly, C.E. “The Early Tudors, Henry Vii.: Henry Viii., by the Rev. C. E. Moberly.” HathiTrust, 2020. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015027330466&view=1up&seq=17&skin=2021.

- Moore, Alan. “Accounts and Inventories of John Staryling, Clerk of the King’s Ships to Henry IV.” The Mariner’s Mirror4, 1914.

- Moorhouse, Geoffrey. Great Harry’s Navy: 0297645447. London, UK: Phoenix, 2006.

- Nelson, Arthur. The Tudor Navy: The Ships, Men, and Organisation, 1485-1603. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2001.

- Oppenheim, Michael. “A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy and of Merchant Shipping in Relation to the Navy, from MDIX to MDCLX with an Introduction Treating of the Preceding Period.” HathiTrust. Accessed August 14, 2022. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x000380522&view=1up&seq=17&skin=2021.

- Richmond, C.F. “English Naval Power in the Fifteenth Century.” History 52, no. 174 (1967): 1-15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24406260.

- Rodger, N.A.M. The Safeguard Of The sea: A Naval History of Britain, 660-1649. New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 1999.

- Round, J.H. and M. Oppenheim. “The Royal Navy under Queen Elizabeth.” The English Historical Review 9, no. 36 (1894): 709-15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/547569.

- Sherborne, James. War, Politics and Culture in 14th-Century England. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2003. Accessed July 7, 2022. ProQuest Ebook Central.

- Simons, Eric Norman. Henry VII. New York, NY: Barnes & Noble, 1968.

- Tyler, Patrick Fraser. “England under the Reigns of Edward VI. and Mary.” Google Books. Accessed August 14, 2022. https://books.google.com/books?id=414JAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Venning, Timothy. Royal Mysteries: The Anglo-Saxons And Early Britain. South Yorkshire, UK: Pen and Sword History, 2021.

- Williams, Hamilton. Britain’s Naval Power. London, UK: Macmillan, 1894.

- Winton, John. An Illustrated History of the Royal Navy. Edited by Dr. Chris Howard Bailey. London, UK: Conway Maritime Press, 2005.

- Wright, Thomas. “Queen Elizabeth and Her Times.” Internet Archive. London, H. Colburn, December 20, 2006. https://archive.org/details/queenelizabethhe01wriguoft/page/n9/mode/2up.

Footnotes

- Hamilton Williams, Britain’s Naval Power (London, UK: Macmillan, 1894), 2. ↩︎

- James Henry Ingram, trans. “The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,” Project Gutenberg, March 30, 2023. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/657/pg657.html. ↩︎

- James Henry Ingram, trans. “The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,” Project Gutenberg, March 30, 2023. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/657/pg657.html. ↩︎

- N.A.M. Rodger, The Safeguard Of The Sea: A Naval History of Britain, 660-1649 (New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 1999), 18. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- James Henry Ingram, trans. “The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,” Project Gutenberg, March 30, 2023. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/657/pg657.html. ↩︎

- James Henry Ingram, trans. “The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,” Project Gutenberg, March 30, 2023. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/657/pg657.html. ↩︎

- N.A.M. Rodger, The Safeguard Of The Sea: A Naval History of Britain, 660-1649 (New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 1999), 19. ↩︎

- Ibid., 19. ↩︎

- Idem. ↩︎

- Hamilton Williams, Britain’s Naval Power (London, UK: Macmillan, 1894), 3. ↩︎

- George Molyneaux, “Why Were Some Tenth-Century English Kings Presented As Rulers of Britain?” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 21 (December 2011): 66. ↩︎

- James Henry Ingram, trans. “The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,” Project Gutenberg, March 30, 2023. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/657/pg657.html. ↩︎

- N.A.M. Rodger, The Safeguard Of The Sea: A Naval History of Britain, 660-1649 (New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 1999), 20. ↩︎

- Ibid., 20. ↩︎

Leave a comment