Heroic, brilliant, and even fortunate though Captain Sir Edward Pellew was, such attributes could not be said to have attended his younger brother, Israel. Having been posted captain after serving as a volunteer at his brother’s capture of the French frigate Cléopâtre in the early months of the French Revolutionary War in 1793, Israel’s lot had been to hang on to the coat tails of Sir Edward’s fame. By April 1795 this strategy had secured him the command of the crack fifteen-year-old frigate Amphion (32), and following tedious employment off Newfoundland and in the North Sea, he had received the much-coveted orders in September 1796 to join his brother’s elite squadron which was scooping up prize after prize on the French coast.

On Monday 19 September the Amphion arrived in Plymouth Sound from the North Sea for repairs to her foremast and bowsprit, and to re-victual prior to joining Sir Edward’s squadron. Next morning at 7 a.m. she went up into the Hamoaze, where on the Wednesday she was lashed to a sheer hulk, the Princesa, and a receiving ship, the Yarmouth.

By the afternoon of Thursday 22nd the defective bowsprit had been removed, a replacement had been fixed in place, and the Amphion was under orders to sail on the next day for her new role with Sir Edward’s squadron. For everyone except the gang aloft working on the rigging, it was time for recreation; while some eighteen men were granted liberty ashore, others were allowed to invite their ‘wives’ and families aboard. These women and children numbered as many as one hundred people in all. Meanwhile, Israel was throwing a dinner for an old friend, Captain William Swaffield of the Overyssel (64), and for his first lieutenant, a gentleman who was due to be superseded by Alexander Wilmot Schomberg, although that officer had not yet arrived to take up the appointment. Meanwhile another officer, Captain Charles Rowley of the Unité (38), had also been due to dine aboard the Amphion that afternoon, but he had been detained by the port admiral, Sir Richard King. The delays would prove fortunate for both Rowley and Schomberg, as the meal was suddenly interrupted in the most dramatic of fashions at 4.15.

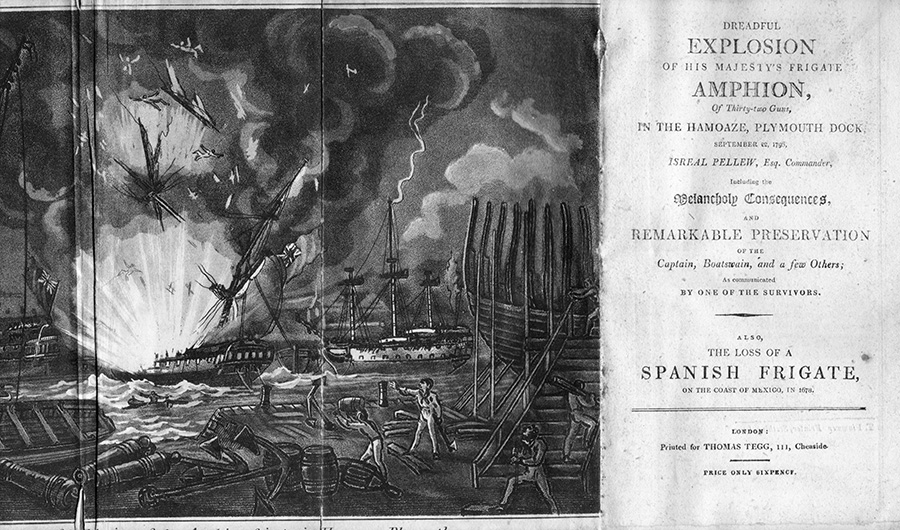

It all began with a hissing noise that was followed by a rumble. Sensing danger, Israel and the lieutenant scrambled to their feet and ran towards the quarter galley. Almost immediately, a huge explosion rent through the fore part of the ship, blasting it to fragments. The remaining part of the Amphion shot upwards, almost revealing her keel, her masts were launched higher into the air than the sheer hulk alongside, the shockwave shook the dockyard and residences nearby, and the boom was loud enough to be heard at Stonehouse two miles away. Ashore, the people of Plymouth scattered in great confusion as the sky turned red.

As the explosion occurred, Pellew was thrown vertically against the upper deck carlings and left temporarily stunned. Regaining his senses, he launched himself out of the shattered stern windows onto the hulk lying alongside. The lieutenant miraculously escaped injury by jumping out of another stern window and swimming for his life. The cabin sentry survived too, although he was never able to recall how. Up forward, the boatswain, Henry Montandon, who had recently joined the Amphion from the Russell (74), and who had been working at the cathead, was propelled into the water and had to disentangle himself from the rigging before being picked up by a boat, his arm broken. Equally fortunate were three of the men who were at work in the tops and had been blown clear of the stricken ship.

However, the majority of those on board were not so lucky. Along with Captain Swaffield, an estimated three hundred and fifty men, women, and children perished on the packed frigate, and once the Amphion had all but disappeared to leave just the stump of her mizzen mast visible, many of their fragmented corpses and limbs surfaced to be left tossing amongst the waves and splintered planking. A number of cannons and mangled bodies had been blown onto the Princesa’s deck, although astonishingly, the sheer hulk and all the men who had been working aboard her were undamaged. Even more astoundingly, some diners aboard the Yarmouth believed that the explosion had been nothing more than a cannon going off, and they continued their meal until they heard the confusion on deck above them.

As soon as he could, Admiral King repaired aboard the hulk where he beheld a shocking tableau of bloodied and burned timbers, distorted lifeless limbs, and wreckage from the Amphion lying under her pendant and the web of her rigging. Gathering as much personal detail as he could, he wrote to the Admiralty listing the names of the survivors, of whom the only officers were Israel and Lieutenant James Muir. Others to escape with their lives were the armourer, boatswain, a master’s mate, twenty-three seamen and a dozen marines, although King added a caveat that more might have survived who were ashore. Among the dead were a junior lieutenant by the name of John Hearle, the sailing master, John Mitchell, the lieutenant of marines, Colin Campbell, and the surgeon, gunner, and carpenter. Most unfortunately, an upholsterer, a Mr Spry, who had gone aboard to see his son, had also died, as had his brother.

For many of the locals it proved to be a desperately sad day, for the Amphion had largely been manned by seamen from the town. Those injured men who survived were conveyed to the Royal Hospital, where anxious relatives gathered outside the gates for news of their family members. Also delivered to the hospital were sacks containing the burned limbs and other body parts of the dead, whilst some forty-two bodies were brought in, including those of six young women, which were all placed in the bone house before being interred in the grounds. As time passed, the task of identifying the other bodies that had been retrieved proved virtually impossible, but those that could be distinguished were buried by family and friends. Meanwhile, bits of the forward part of the frigate were recovered and brought on shore to the wet slip, including the apparently undamaged figurehead.

Following the explosion, Israel had been carried in shock to the house of the commissioner, Captain Robert Fanshawe, where he had remained in convalescence for a couple of days, nursing burns to his face and chest. On 25 September, he and other surviving members of the crew attended Charles Church in the town to give thanks for their preservation. A month after the explosion, on 22 October, Captain Swaffield’s body floated up from the wreck. His skull had been crushed although his body was not mutilated in any way, whilst his uniform was intact, and a watch and four guineas were found in his pocket. His remains were taken in a hearse to Stonehouse to be buried that evening in the chapel.

An inquiry into the tragedy was conducted, which established that the Amphion’s gunner had been fraudulently purloining gunpowder to sell on the black market, and that he had left a trail of powder leading to the fore magazine, which had ignited. On 3 October, the frigates Castor(32) and Iphigenia (32) were lashed alongside the remains of the Amphion, which mainly consisted of the rear part of the ship. They attempted to raise it, but bad weather delayed the effort, and when more bodies began pouring out of her, she was dragged to the jetty and broken up.

Following intense lobbying by his brother, Israel was soon appointed to another frigate. However, he had barely commanded her for a matter of weeks before the crew cast him ashore during the fleet mutinies of 1797, accusing him of cruelty. Again, Sir Edward found Israel another command, the Cleopatra, but after going out to the West Indies he lost his first lieutenant and a number of men in an ill-advised attack on a Spanish convoy off Cuba. The frigate later had to jettison her guns after grounding in the Bahamas. One can only imagine therefore, the additional consternation felt by the defeated Vice-Admiral Pierre Villeneuve at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, where after his flagship had struck her colours to ‘Captain Pellew’s Conqueror’, he found that it was not to the celebrated Sir Edward that his sword would be surrendered, but rather to the hapless Israel.

Richard Hiscocks

Richard Hiscocks is the founder and co-author with naval historian Paul Martinovich of the ‘more than Nelson’ website, a biographical history and chronicle of the Royal Navy from 1776-1815. https://morethannelson.com/

Leave a comment