Background: A New Nation and Its Rich Fisheries

In the late 19th century, Canada’s coastal fisheries were not just an economic lifeline – they were a matter of sovereignty. The new Dominion’s Atlantic waters teemed with valuable fish stocks that attracted foreign fishing fleets, especially from the United States. Protecting these resources quickly became a national priority. Yet, as a colony-turned-Dominion of the British Empire, Canada initially relied on Britain’s Royal Navy for maritime defense. This reliance soon proved problematic: British warships were sparse in North American waters and often reluctant to risk diplomatic trouble with the Americans over fisheries disputes.

At Confederation in 1867 , when Canada officially became a Dominion, it lacked any formal naval force of its own. The British focus was on defending Canada’s land borders, leaving the seas largely unpoliced. Fish, however, were big business – cod, herring, salmon and other catches fed local economies and export markets. More importantly, controlling adjacent fisheries was seen as a symbol of sovereignty for the young nation. Canadian politicians grew frustrated watching American schooners cast nets in Canadian waters with impunity, while British officials were hesitant to intervene and enforce existing fisheries agreements so as not to risk a quarrel with the US. This tension set the stage for Canada to take matters into its own hands.

The Need for a Canadian Solution

From the outset, Canadian leaders realized they had to assert control over their offshore interests – even without a navy. As one historian noted, the fundamental cause of Canada’s early naval efforts was the failure of the imperial government to defend Canadian fish from American poachers. In other words, Britain’s laissez-faire approach to American encroachment forced Canada’s hand. Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald, usually a loyal imperialist, “forced the hands of British ministers to protect the Canadian fisheries when they were not [so inclined]”.

By 1870, the British North America and West Indies Squadron – the local Royal Navy detachment – had informed Ottawa it would no longer patrol Canada’s Atlantic fisheries. The British government flatly “refused the continued use of the RN’s Atlantic Squadron to patrol Canadian fisheries”, effectively telling Canada to fend for itself. In response, that same year the Department of Marine and Fisheries cobbled together a small domestic force known as the Marine Police. This ad hoc unit consisted of the steamship Lady Head and six schooners, tasked with cruising the coastal waters to “prevent encroachment upon [Canada’s] inshore fishing grounds”. It was a purely Canadian initiative – funded by Ottawa, crewed by Canadians – and it marked the first step toward an independent maritime enforcement capability.

The creation of the Marine Police in 1870 paid immediate dividends. Canadian patrol vessels began confronting American fishermen who ventured inside the three-mile limit (the internationally recognized boundary for territorial waters at the time). This show of resolve helped prod Britain and the United States to negotiate a diplomatic compromise: the Treaty of Washington (1871). Under the treaty’s fisheries articles, Americans were allowed limited access to Canadian inshore fisheries in exchange for financial compensation to Canada. With an agreement in place, the crisis abated and the Marine Police was disbanded as “it was thought” foreign incursions would cease.

However, the calm proved temporary. The treaty’s fisheries clause had a time limit. In 1885, the United States unilaterally abrogated (withdrew from) the treaty’s fisheries provisions when they expired. Suddenly, Canadian waters were again off-limits to Americans, and Canadian authorities braced for a return of illicit fishing. Sure enough, U.S. schooners soon swarmed into the Atlantic fisheries without licenses, testing Canada’s resolve. Confronted with this challenge and little appetite from Britain to send warships, Canada acted decisively – launching what would become the Fisheries Protection Service.

Founding of the Fisheries Protection Service (FPS)

In 1886, the Canadian government formally re-activated and expanded its fisheries patrols as a permanent Fisheries Protection Service (FPS). This can be seen as the birth of a “quasi-naval” force for Canada – decades before an official navy existed. The FPS was established under the Department of Marine and Fisheries and was imbued with a distinctly Canadian character. Its mandate was clear: protect Canada’s fisheries from foreign intrusion and uphold Canadian sovereignty in territorial waters.

Ottawa spared no time in building up this service. By the 1890s, the Department of Marine and Fisheries had acquired a sizable fleet for patrol duties – including eight armed cruisers and numerous smaller vessels. These patrol ships flew the Canadian blue ensign and even “the ‘whip lash’ pennant of a man-of-war,” and their crews wore uniforms closely resembling those of the Royal Navy. In effect, Canada had improvised a miniature navy dedicated to fisheries protection. As a U.S. State Department report observed at the time, Canadian authorities had made “preparations, in the way of a marine police force, very much as we now witness” to guard their fishing grounds. What had begun as a few rented schooners was now a permanent federal service – Canadian-funded, Canadian-led, and Canadian-controlled – enforcing the nation’s laws at sea.

Crucially, the Fisheries Protection Service was born from Canadian initiative in the face of imperial ambivalence. Whereas the Royal Navy focused on great-power rivals elsewhere, the FPS patrolled the foggy bays of Nova Scotia and the rocky inlets of Newfoundland (then a separate colony) where poachers lurked. It was a local solution to a local problem, and Canadians were proud of it. One British observer even noted that by the 1880s the FPS had effectively become “a small paramilitary fleet” of its own. This was nation-building at sea: a generation of Canadian sailors and officers gained experience in maritime law enforcement, navigation, and command – experience that would later prove vital when Canada created a true navy.

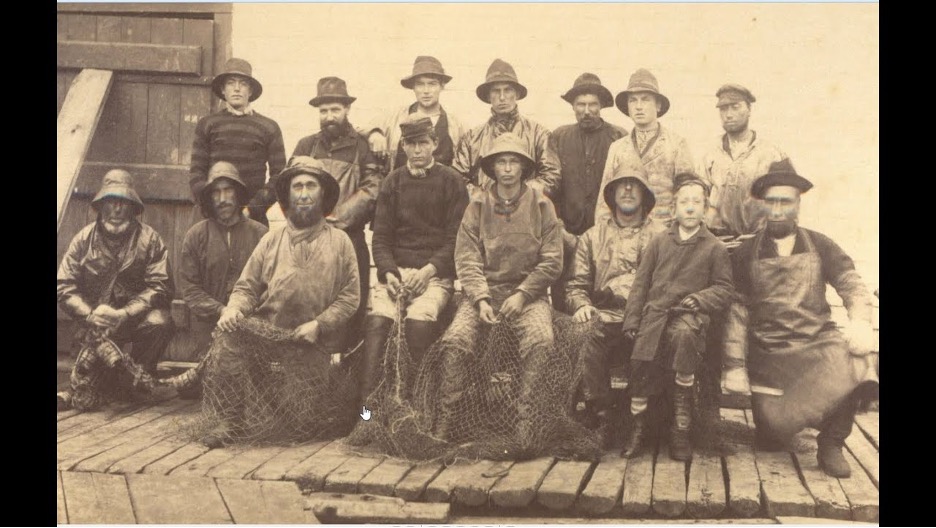

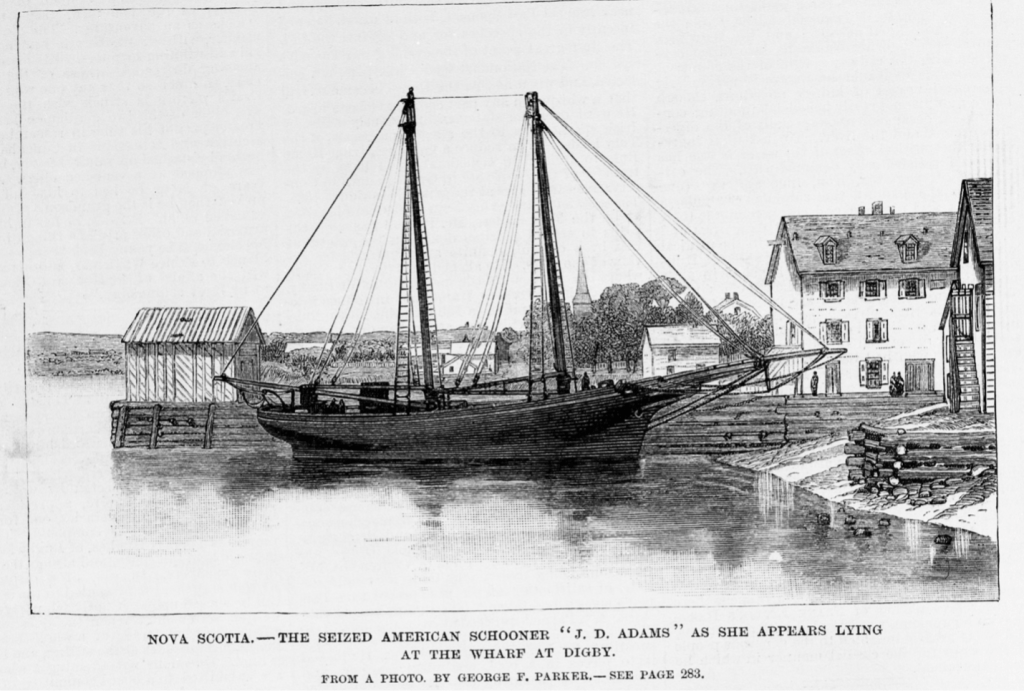

Only days later, a second U.S. vessel met a similar fate. The schooner Ella M. Doughty of Portland, Maine was seized on May 17, 1886, at St. Ann’s, Cape Breton, for infringing Canadian customs and fisheries laws. In both cases, Canadian officers boarded the foreign schooners and escorted them to port as prizes for adjudication. These assertive actions caused a diplomatic stir – American fishermen and media railed against Canada’s crackdowns, one outraged captain even decrying “cheap Canadian pirates seizing my schooner”. U.S. newspapers fumed at the impounded vessels, and Washington demanded explanations. But Canada held firm, insisting that its laws would be respected within its waters.

The “fisheries war” of 1886–1887 saw over a dozen American schooners either seized, detained, or warned off by the Fisheries Protection Service. Canadian cruisers – often old wooden steamers or sailing gunboats – doggedly shadowed the New England fishermen, ready to pounce the moment they breached the three-mile limit or tried to enter Canadian harbors for bait or shelter without permission. According to a U.S. Senate report, incidents piled up: the Sarah B. Putnamchased out of a Nova Scotia harbor during a storm, the Seth Stockbridge and the Annie M. Jordan warned off from New Brunswick waters, and more. American crews complained of being harassed and “rudely treated” by Canadian officials, while Canadians saw it as simply enforcing their sovereignty.

These enforcement actions were not without risk. The United States government dispatched naval vessels to the region as tensions mounted, raising the specter of a direct military confrontation. In one notable episode of tit-for-tat, American authorities retaliated by seizing Canadian vessels engaged in sealing in the distant Bering Sea – far from Atlantic fishing grounds but indicative of broader maritime disputes. In August 1886, the American cutter Richard Rush captured the British-Canadian schooner W.P. Sayward for hunting seals in what the U.S. claimed (at the time) as its preserve. Incidents like this – on the opposite side of the continent – drove home to Canadians that their maritime interests were vulnerable so long as they lacked strong naval forces. Britain eventually negotiated a settlement in the Bering Sea dispute (with an arbitration ruling in 1893), but many in Ottawa felt that Canadian lives and property had been used as bargaining chips.

Despite these challenges, the Fisheries Protection Service’s dogged patrols did yield a form of deterrence. By 1888, Britain and the United States attempted a new fisheries treaty, and although the American Senate failed to ratify it, an interim modus vivendi was reached that calmed the Atlantic fishery disputes for a time. Through it all, the FPS remained on guard each season, ready to confront any “encroachment upon their inshore fishing grounds”. Its reputation grew as a stalwart guardian of Canadian sovereignty – a role made all the more critical after 1904 when Britain, focusing on European threats, withdrew the last of its naval ships and crews from Canada’s coasts. The Royal Navy closed its historic bases at Halifax and Esquimalt in that year, effectively handing full responsibility for local maritime defense to the Dominion. Canada’s little fisheries fleet suddenly stood as the only game in town.

Notable Incidents and Vessels in Early Fisheries Protection (1870–1910)

To appreciate the evolution of Canada’s pre-Navy maritime efforts, here is a timeline of notable incidents and milestones involving the Fisheries Protection Service and its predecessors:

| Date | Location | Incident or Vessel | Description |

| 1870 | Bay of Fundy, Atlantic Coast | Marine Police formed | Canada creates a small patrol squadron (steamer Lady Head + 6 schooners) to guard fisheries after Royal Navy withdrawal. First assertion of Canadian control at sea. |

| May 7, 1886 | Digby, Nova Scotia | Seizure of David J. Adams | FPS cruiser Lansdowne seizes American fishing schooner for illegal fishing (buying bait) in Canadian waters. Sparks international dispute and U.S. protests. |

| May 17, 1886 | St. Ann’s, Cape Breton | Seizure of Ella M. Doughty | Canadian officials capture a second U.S. schooner for customs/fisheries violations, underscoring Canada’s resolve to enforce its laws. |

| 1886–1887 | Atlantic Canada | “Fisheries War” incidents | Over a dozen American vessels seized, detained, or warned off by Canadian cutters enforcing the 3-mile limit. U.S. Navy dispatches ships as tensions rise. |

| 1904 | Halifax, NS (East Coast) & Great Lakes | New cruisers Canadaand Vigilant | Laurier government buys two modern, fast patrol ships for the FPS – the 200-foot steel steamer CGS Canada (built in Britain) and CGS Vigilant (built in Toronto). These armed cruisers are intended as the nucleus of a future navy. |

| 1905 | Halifax & Esquimalt | Royal Navy withdrawal | Britain closes its Canadian naval bases and withdraws warships. The FPS, now militarized, becomes Canada’s sole naval force on each coast, carrying the burden of maritime defense. |

| May 4, 1910 | Ottawa (Parliament) | Naval Service Act passed | Canada formally establishes the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN). The Fisheries Protection fleet and personnel provide a foundation – e.g. FPS’s flagship Canada is commissioned as Canada’s first naval training ship. The era of an ad-hoc fisheries navy transitions to an official Canadian Navy. |

Table: Key events, incidents, and vessels in Canada’s early fisheries protection efforts (pre-1910).

“A Distinctly Canadian Enterprise”: National Identity and Legacy

The Fisheries Protection Service was more than an ad hoc police force – it became a point of pride and a stepping stone toward Canadian nationhood. It demonstrated that Canada could exercise sovereignty in practical ways, even in the shadow of the British Empire. Canadian sailors enforcing Canadian law against foreign violators in Canadian waters was a powerful assertion of autonomy. As historian Marc Milner observed, by 1904 some Canadians were pointing out that “a century ago… we already had a navy – the Royal Navy”, but the short answer to why Canada needed its own was the imperial government’s failure to guard Canadian fisheries. In other words, Canada’s coast guard of the 1800s had become the seed of a navy out of necessity.

Politically, the FPS’s success strengthened Canadian confidence. English-Canadians largely supported robust enforcement at sea, seeing it as defending national honor against American intrusion. French-Canadians, who were often wary of imperial adventures, were also supportive because fisheries protection was a local defense issue with no imperial entanglement. (Even the ardent nationalist Henri Bourassa – a vocal critic of Canadian military entanglement overseas – “admitted… that there was a need for fisheries protection”) Thus, fisheries patrols were a rare point of consensus between English and French Canada on matters of defense. It was a distinctly Canadian enterprise viewed as protecting Canadian homes and livelihoods, not the distant Empire.

This domestic legitimacy proved vital in the debates that followed. By the early 1900s, as global naval competition intensified (the era of HMS Dreadnought and the Anglo-German naval race), Britain began urging dominions like Canada to contribute more to imperial naval defense. Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier deftly argued that Canada’s contributions would be on its own terms. He noted that Canada was already maintaining a fisheries patrol fleet – taking on local defense burdens that “relieved Britain’s overstretched forces”. Laurier’s government explicitly cast the Fisheries Protection Service as the “nucleus” of a future Canadian Navy. In 1902, Laurier went to the Imperial Conference in London and, rather than simply writing a cheque for the Royal Navy, announced that Canada would develop a local naval service under Canadian control. This was effectively an extension of the FPS concept. Minister of Marine and Fisheries Raymond Préfontaine took up the task: he proposed to “militarize the FPS” and even drafted a Naval Militia Bill to begin training Canadian sailors on the new cruisers Canada and Vigilant. Though Préfontaine’s untimely death in 1905 delayed the plans, his work continued to echo in what followed. His successor, Louis-Philippe Brodeur, continued expanding the service and even hired Britain’s Captain Charles Kingsmill, RN – a Canadian by birth – to oversee the Marine Service. Kingsmill would soon become the first director of the new navy, reinforcing Canada’s evolving maritime identity.

When the Royal Canadian Navy was finally established in 1910, it owed a great debt to the Fisheries Protection Service. Many of the RCN’s first vessels and crew came directly from the FPS. For example, the patrol vessel CGS Canada was commissioned as HMCS Canada, becoming the young navy’s training ship. Several other fishery cruisers, like CGS Petrel and CGS Curlew, were incorporated into naval service during World War I. The organizational know-how – from ship maintenance to coastal surveying and communications – developed in the FPS provided an essential foundation for a full-fledged navy. As one contemporary put it, “the fisheries protection service… formed the kernel from which the navy would ultimately spring.”

Equally important, the ethos of the FPS influenced Canadian naval culture. The Service had always been about defending home waters and Canadian interests first. This ethos helped shape the RCN’s early identity as a navy intended to serve Canada’s needs (such as coastal defense and patrol) rather than merely an adjunct to the Royal Navy. It also influenced public support: Canadians could look at their new navy and see an extension of something familiar – those hardy fisheries patrol ships that had kept their waters theirs. In a sense, the FPS bridged the gap between colonial dependency and national self-reliance at sea.

From Fishing Grounds to a Navy of Our Own

“What she [England] wants is the hearts, the brains, and the brawn of her subjects all over the world… would not the impression be more greater yet if… the young nations seated over the whole world [were] building fleets of their own.” – Sir Wilfred Laurier

In the pre-Navy era of the late 1800s, Canada learned to navigate its own course on the high seas – starting with the protection of fisheries and ending with the birth of the Royal Canadian Navy. The Fisheries Protection Service, though modest in size, was monumental in significance. It was Canada’s first naval force in all but name, forged in response to very real threats to the young nation’s resources and sovereignty. Through bold actions like the seizure of poaching schooners, Canada sent an early message that it would stand up for itself, even on water. These efforts bolstered Canada’s confidence as a sovereign nation and provided practical experience in naval affairs.

By emphasizing a distinctly Canadian solution to maritime problems, the FPS set the pattern for Canada’s approach to defense: cooperation with Britain when feasible, but independent action when necessary for national interests. The political battles that accompanied the founding of the Royal Canadian Navy (with Canadians debating the cost, purpose, and control of a navy) were heavily informed by the FPS experience. After all, it was easier to argue for a Canadian navy when a Canadian fisheries fleet had already been successfully protecting Canadian shores for decades.

In retrospect, the saga of the Fisheries Protection Service is an engaging chapter of Canadian history – one filled with wooden schooners and steam cruisers, diplomatic squabbles and high-seas drama. It is the story of how a fledgling nation, lacking a navy but brimming with determination, gradually affirming its sovereignty through consistent enforcement of maritime laws and control over its waters. These unsung patrol ships and their crews earned Canada a place at the maritime table and helped ensure that when Canada’s navy finally set sail in 1910, it did so with a proud Canadian identity and a legacy of vigilance inherited from the Fisheries Protection Service.

In the words of a British official reflecting on the 1870s disputes, the Canadians had been “charged with the administration… to prevent encroachment upon their inshore fishing grounds” – and they had risen to that charge admirably. The “Stewards of Sovereignty” in the age before a navy laid the keel for Canada’s naval future, proving that Canada could, and would, defend its own waters come what may.

Ayaan Seth

Sources:

- Milner, Marc. Canada’s Navy: The First Century. University of Toronto Press, 1999. (Key background on Canada’s early naval history and Fisheries Protection Service.)

- Tucker, Gilbert Norman. The Naval Service of Canada: Its Official History. King’s Printer, Ottawa, 1952. (Official historical account detailing the Fisheries Protection Service’s evolution into the Royal Canadian Navy.)

- Johnston, William, William Rawling, Richard Gimblett, and John MacFarlane. The Seabound Coast: The Official History of the Royal Canadian Navy, 1867–1939. Dundurn Press, 2010. (Comprehensive reference on maritime protection and the political implications for sovereignty.)

- Gough, Barry. Britannia’s Navy on the West Coast of North America, 1812–1914. Heritage House Publishing, 2016. (Context on British naval presence and its limitations, influencing Canadian decisions.)

- Macdonald, Fraser. Canada’s Navy: Naval Service in a Sovereign Nation. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2015. (Discusses Canadian assertion of maritime independence separate from British colonial interests.)

- Department of Marine and Fisheries Annual Reports (1870–1910). Public Archives Canada.

(Official government reports detailing establishment, operations, and specific actions of the Fisheries Protection Service.)- The Naval Service Act, 1910. Statutes of Canada.

(Primary legislative document establishing the Royal Canadian Navy.)- Treaty of Washington (1871).

(Official treaty document outlining fisheries agreements between Canada and the United States.)- Parliamentary Debates (House of Commons, 1880–1910). Library and Archives Canada.

(Political discussions reflecting on maritime sovereignty, fisheries protection, and early naval debates.)- Halifax Chronicle, Nova Scotia (1886–1904).

(Coverage of local fisheries protection incidents, notably seizures of foreign fishing vessels.)- The Globe (Toronto), late 19th Century issues.

(Reports and editorials discussing fisheries protection, national sovereignty, and related political debates.)- The Evening Telegram (St. John’s), 1886–1904.

(Local reporting from Newfoundland perspective on fisheries protection and sovereignty.)- Boston Daily Globe, 1886–1887.

(American perspective covering incidents such as the seizures of American schooners, providing an outside viewpoint.)- United States Senate Documents (1886–1888), Volumes related to Canadian fisheries disputes.

(Detailed American government records documenting responses to Canadian enforcement actions.)- British Foreign Office Correspondence (Public Records Office, UK).

(Diplomatic communications between Britain, Canada, and the United States regarding fisheries and maritime sovereignty.)

Leave a comment