The year is 1758, and the Seven Years’ War has been raging around the world for nearly two years with no clear victor in sight. The Royal Navy was working tirelessly to deliver a decisive victory for king and country. On 14 July, Prime Minister William Pitt the Elder ordered the construction of 12 additional ships of the line to bolster the fleet, including one first-rater. A few days later, at Chatham Dockyard, construction began on a leviathan destined to change the course of history.

“no one could have predicted the name she would eventually bear—a name once marred by tragedy.”

When the keel of the Victory was laid down, no one could have predicted the name she would eventually bear—a name once marred by tragedy. The previous Victory, launched in 1737, was also a first-rate ship of the line. Unlike her successor, however, this Victory had a brief and ill-fated career. On the night of October 4–5, 1744, the massive battleship foundered during a violent storm in the English Channel.

Initially, it was deemed inappropriate to revive such an unlucky name. However, at the insistence of William Pitt the Elder, the name was given new life after Britain celebrated one of the most successful military years in its history: 1759. During this annus mirabilis, the Royal Navy decisively defeated both the French Mediterranean and Atlantic fleets, leaving French forces in Canada completely isolated. Following the fall of Quebec, the fate of North America was effectively sealed. To commemorate this extraordinary series of victories, Pitt insisted that the next first-rate ship bear the name Victory. The name was officially bestowed in October 1760.

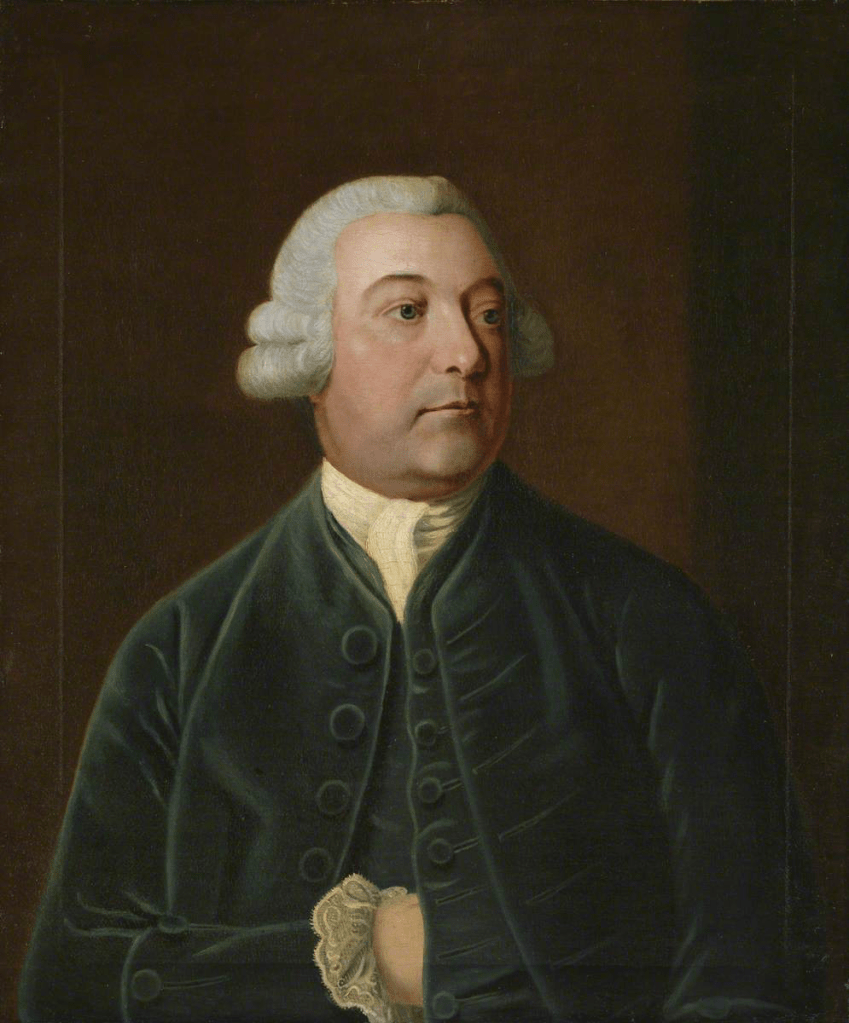

HMS Victory was the brainchild of the legendary shipwright Sir Thomas Slade. Appointed Surveyor of the Navy in 1755—thanks to the support of his patron, First Lord of the Admiralty George Anson—Slade was brought in amid growing frustration over the stagnation of British warship design. After years of neglect, he was tasked with setting things right—and he rose to the challenge brilliantly. Slade perfected the design of the 74-gun third-rate ship of the line and the frigate, establishing what would become the backbone of the Royal Navy for the next fifty years. Between 1749 and 1769, he designed no fewer than 181 warships. Yet it was the behemoth taking shape on the stocks at Chatham that would ultimately define his legacy.

The lines of Victory were largely based on those of HMS Royal George, launched in 1756 and, at the time, serving as the flagship of Admiral Sir Edward Hawke—the man who famously defeated the French Atlantic Fleet at Quiberon Bay. Royal George itself was heavily influenced by French warship design. It was no secret that Britain had much to learn from its maritime rival in the art of shipbuilding. French shipwrights repeatedly demonstrated their superiority, approaching naval architecture with a more scientific and methodical mindset. Notably, Victory‘s hull shape and her more vertical sternpost—which greatly improved responsiveness to the helm—were both inspired by French precedents.

The laying down of her keel was a momentous occasion. HMS Victory was, in fact, one of only 22 first-rate ships of the line built for Britain throughout the 17th and 18th centuries—averaging just one every eight years. The keel-laying ceremony was attended by Prime Minister Pitt and several representatives of the Admiralty, who traveled from London for the event and later dined with dockyard officials to celebrate the occasion.

The master shipwright originally tasked with overseeing construction was John Lock. Following Lock’s death, responsibility passed to Edward Allin, the son of a former Surveyor of the Navy. The warship was laid down in the Old Single Dock at Chatham, which was later renamed Victory Dock in honor of its most renowned wooden creation. Approximately 150 men were employed in her construction.

“Around 6,000 trees (equivalent to 300,000 cubic feet of timber) were felled to build the ship—representing roughly 40 hectares (100 acres) of woodland.”

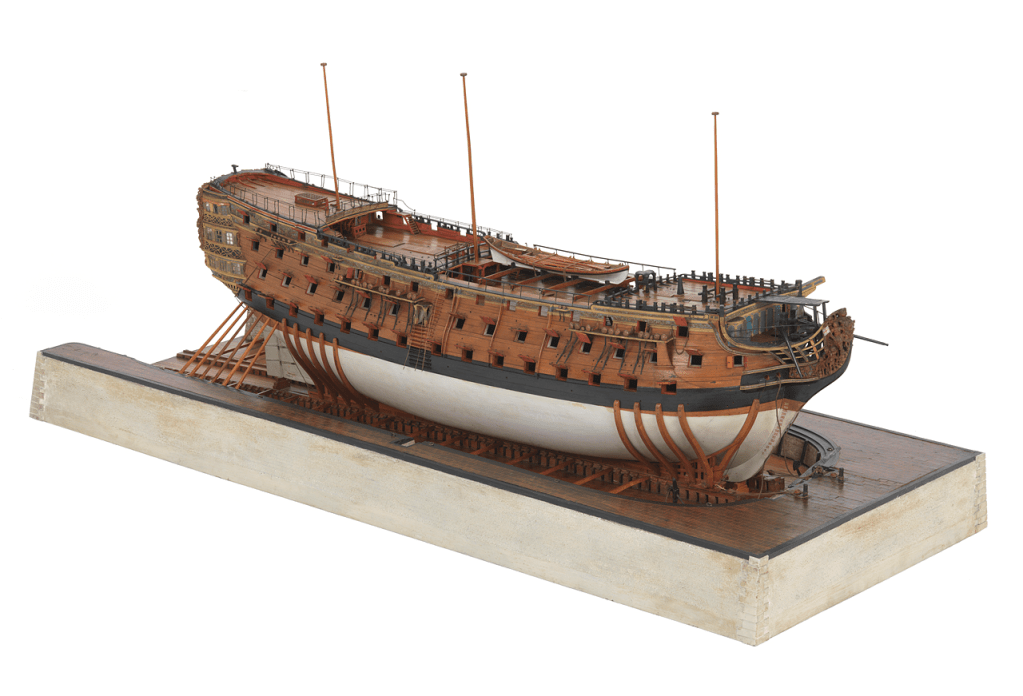

Victory was a 3,500-ton ship, measuring about 70 meters in length, 15.8 meters in beam, with a draught of 8.76 meters—making her slightly larger than her predecessor, the Woolwich-built HMS Royal George. Around 6,000 trees (equivalent to 300,000 cubic feet of timber) were felled to build the ship—representing roughly 40 hectares (100 acres) of woodland. About 90% of the timber was native English oak, specifically from the Weald forests of Kent. This was among the sturdiest wood available and thus ideal for a warship destined to endure the full force of enemy broadsides.

Various other types of wood were used in Victory’s construction: hazel, yew, rowan, ash, beech, silver birch, black poplar, alder, and elm—for the keel. Pine, imported from New England, was used for the lower masts. Many of the hardwoods were sourced from the Baltic states. Six-foot copper bolts held the massive frame together, while treenails were used for smaller fittings.

Construction slowed after the French Navy was decisively defeated in the “Year of Victories,” which ironically benefited the ship’s longevity. Victory was left “in frame” much longer than usual, allowing the timbers to settle and dry thoroughly. While most ships stood in frame for a few months, Victory remained so for a full three years.

Work resumed in the autumn of 1763, and her hull was completed by April 1765. HMS Victory was launched on 7 May 1765, an event marked by invitations to the Prime Minister, members of his cabinet, and several parliamentarians. The launch, however, was not without incident: Victory was too broad to pass through the dock gates. Dozens of shipwrights rushed to the scene and used their adzes to chip away enough wood from the gates to allow her passage. The ship ultimately cost the British government £67,176 3s 0d—equivalent to approximately £46.5 million in today’s currency.

Other problems surfaced in the days following Victory‘s launch. A significant list to starboard alarmed the shipwrights, who resolved the issue by adding and redistributing ballast. Another concern was that Victory sat too low in the water, bringing her lower gundeck dangerously close to the waterline—posing a serious risk in rough seas. As a result, her captains were instructed never to open the lower gunports during heavy weather. Fate, however, spared Victory from fighting her battles in such conditions, allowing her to unleash her full firepower when it counted.

“Once her masts were in place, the ship towered 62.5 meters above sea level. To put that into perspective: if you placed Victory next to the Colosseum, you’d still need an extra 10 meters for the Roman amphitheater to match her height. “

Following the cessation of hostilities with France, Victory was placed in ordinary. Her rigging was gradually fitted over the following years. Once her masts were in place, the ship towered 62.5 meters above sea level. To put that into perspective: if you placed Victory next to the Colosseum, you’d still need an extra 10 meters for the Roman amphitheater to match her height. Powered by 37 sails spanning approximately 5,468 square meters, the ship could reach speeds of up to 11 knots. She required a crew of 850 men to operate.

Sea trials were completed in 1769, after which Victory returned to her mooring. When war with the American separatists broke out in 1776, she was not initially commissioned. Victory was deemed too large to operate effectively along the North American coast, and the limited naval threat posed by the fledgling American navy didn’t warrant deploying such an expensive first-rate ship. That changed when France entered the war. Victory was prepared for operations in European waters against Britain’s longtime rival—but before she could put to sea, she first had to be armed.

As a 100-gun warship, her armament was distributed across multiple decks: twelve 6-pounders were mounted on the quarterdeck and forecastle (the upperworks); 30 12-pounders lined the upper deck; 28 24-pounders were fitted to the middle deck; and the lower gundeck—the main strike force of any first-rater—carried 30 massive 42-pounder guns.

Over time, however, many changes were made to her armament. The enormous 42-pounders, while powerful, were unpopular among Royal Navy officers due to their slow rate of fire. Many preferred the quicker-firing 32-pounders. When Admiral Augustus Keppel hoisted his flag aboard Victory in 1778, he promptly ordered the 42-pounders replaced with 32-pounders. After he struck his flag, the 42-pounders were reinstalled. Later, Admiral Nelson—who shared Keppel’s preference—again chose 32-pounders for the lower gundeck.

“the total weight of firepower Victory unleashed at Trafalgar exceeded the entire artillery strength available to Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.”

Following the American War of Independence, Victory‘s upperworks were also upgraded: the 6-pounders were replaced with 12-pounders, and two carronades were added to the quarterdeck. At Trafalgar, she carried an additional two 12-pounders on the quarterdeck, officially making her a 104-gun first-rate ship of the line. Not long after the momentous battle off Cape Trafalgar, her 24-pounders were replaced with 18-pounders—until the 24-pounders returned to her middle deck in 1828.

Regardless of the configuration, her firepower was staggering. To put it into perspective: the total weight of firepower Victory unleashed at Trafalgar exceeded the entire artillery strength available to Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

HMS Victory went on to have a distinguished career, fighting in numerous battles during the War of American Independence as well as the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. She served as the flagship of naval legends such as Augustus Keppel, John Jervis, and Lord Nelson. It was on the backs of beasts like these that the British Empire was built and the modern world began to take shape. Victory can still be admired today at the Historic Dockyard in Portsmouth.

Olivier Goossens

Leave a comment