After the failed siege of Toulon, the Royal Navy was still in need of a proper naval base in the Mediterranean. This need became even more pressing when the Allied position in Spain was compromised following the Battle of Almansa. On 25 April 1707, the Duke of Berwick inflicted a crushing defeat on the combined English, Dutch, and Portuguese army in the Iberian Peninsula, reducing their presence to Catalonia. As a result, securing Catalonia for Archduke Charles—now King Charles III of Spain—became the new priority for the Alliance. However, the Allied forces in and around Barcelona were struggling with severe provisioning issues. Establishing a permanent naval base in the western Mediterranean was seen as essential to ensuring the steady flow of troops and supplies to the Spanish front. Port Mahon, Minorca, emerged as the preferred target.

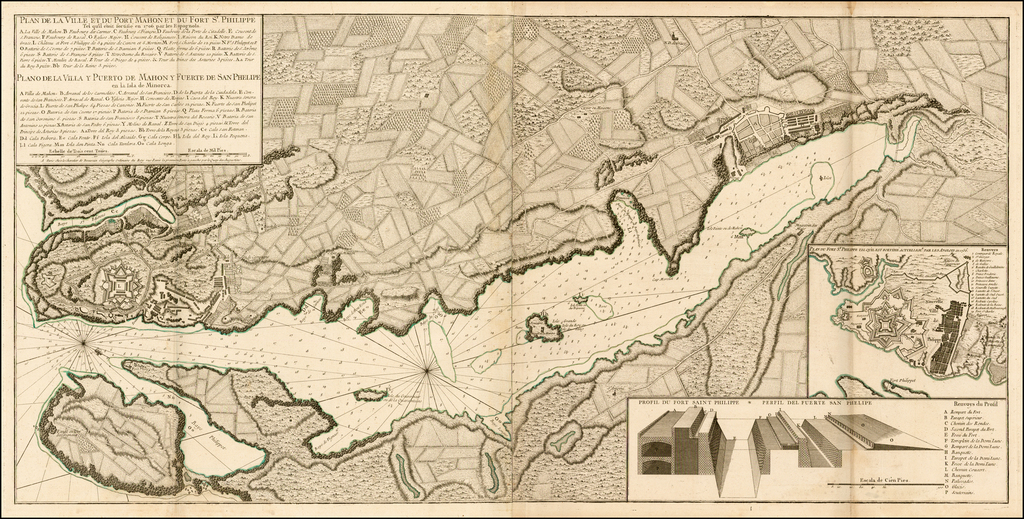

Port Mahon, the English name for Mahón, is currently the capital and second-largest city of Minorca. Even in the past, the port city held significant strategic advantages due to its immense natural harbor. In fact, Port Mahon boasts one of the longest natural harbors in the world, measuring approximately 3 miles (5 kilometers) in length and 3,000 feet (900 meters) in width.

At the time, Port Mahon was well defended, with a strong and well-supplied garrison of 1,000 men under the command of the Marquis de la Jonquière. A seasoned and trusted commander, Jonquière was deeply committed to keeping the Bourbons in control of the city. The Franco-Spanish forces were concentrated at the mighty Fort St. Philippe (Castell de Sant Felip), the fortress guarding the entrance to the natural harbor.

Port Mahon had been on the British radar for quite some time. As early as 1702, Prince George of Hesse-Darmstadt had emphasized the strategic importance of this fine deep-water harbor. In 1705, an anonymous pamphleteer reaffirmed the strategic and commercial advantages of adding Minorca to the British Empire in An Inquiry into the Causes of Our Naval Miscarriages.

“I am so entirely convinced that nothing can be done effectually without the Fleet, that I conjure upon you if possible to take Port Mahon.”

However, the British initially did not invade the island, partly due to the Duke of Marlborough’s preference for taking Toulon. Only after the failure at this southern French harbor did Marlborough reconsider Port Mahon, writing to Stanhope: “I am so entirely convinced that nothing can be done effectually without the Fleet, that I conjure upon you if possible to take Port Mahon.”

James Stanhope, the son of English envoy Alexander Stanhope, was an ambitious army officer who had been at the heart of the fighting since the start of the war. Eager for combat, he persuaded his superiors to allow him aboard Admiral Rooke’s fleet en route to Cadiz in 1702. After briefly serving with Marlborough in the Low Countries, Stanhope was sent to Portugal to fight the Duke of Berwick. He was later transferred to the command of Lord Peterborough, serving under him in Catalonia.

“Known for his aggressive leadership, Stanhope was eventually appointed commander-in-chief of the English troops in Spain.”

Known for his aggressive leadership, Stanhope was eventually appointed commander-in-chief of the English troops in Spain. It thus became his responsibility to execute the Allied plan to capture Port Mahon. The energetic commander swiftly assembled a force of 1,700 British, Portuguese, and Catalan troops, along with a siege train of 10 large guns and mortars, to bombard the French and Spanish defenders into submission.

Before advancing on Minorca, however, the Allies first turned their attention to Sardinia. The island was considered strategically valuable due to its abundant annual grain harvest, which could help sustain Allied soldiers in Catalonia. Admiral Leake arrived off Cagliari with his warships on 11 August and summoned the local governor, the Marquis de Jamaica, to surrender. The governor initially refused, but a brief bombardment by the Royal Navy the following day quickly changed his mind.

After capturing Sardinia, Leake arrived off Barcelona to embark Stanhope. This was carried out in utmost secrecy, with the fleet setting sail on 3 September. The expeditionary force was escorted by the frigate HMS Milford and the 60-gun fourth-rate HMS York. Three days later, the fleet reached the coast of Majorca, which was then under Allied control. Stanhope successfully persuaded the local governor to assign 300 men from his garrison to reinforce the English force. Now commanding 2,000 men—outnumbering the defenders of Port Mahon two to one—Stanhope still believed he needed additional troops to ensure the operation’s success. He therefore urged Admiral Leake to detach 600 marines from the fleet to support him. Leake, however, eager to return home like many of his officers, declined, believing he had done enough after the conquest of Sardinia. The British admiral sailed back to England, while Stanhope pressed on toward Minorca.

On 13 September, Stanhope started disembarking his troops and siege train, an operation which lasted for three days and surprisingly went completely unopposed. Stanhope wanted to conclude the mission without bloodshed, entreating the Spanish garrison to join his side. Marquis de la Jonquière’s troops refused, however, and Stanhope prepared to besiege Fort St. Philippe.

“The bombardment of Fort St. Philippe was swift and fierce, bringing down the walls within a matter of hours.”

By 28 September, the battery was in place to shell the Spanish fortress. The bombardment of Fort St. Philippe was swift and fierce, bringing down the walls within a matter of hours. When the Spanish still refused to surrender, Stanhope ordered a general assault, personally leading his soldiers into battle. The defenders fought valiantly, temporarily halting Stanhope’s attack. However, the Spaniards eventually entreated de la Jonquière to surrender. The soldiers had their families with them, trapped alongside them in the beleaguered stronghold and distressed by the relentless shelling.

The Bourbon forces at Port Mahon finally surrendered on 30 September. The French soldiers were shipped to Toulon, while the Spaniards who did not swear allegiance to Archduke Charles were sent to Murcia under parole. Stanhope had prevailed, but he did not rejoice, as he had received news of his brother’s death during the assault.

“England ought never to part with this island, which will give the law to the Mediterranean both in times of war and peace.”

Although the operation against Port Mahon had been carried out in the name of Archduke Charles, the British soon realized they were in possession of a strategic gem. British reluctance to cede the island grew by the day. As Stanhope pointed out, “England ought never to part with this island, which will give the law to the Mediterranean both in times of war and peace.” Indeed, the strategic importance of Minorca transcended its immediate use for the Allied cause in the War of the Spanish Succession. Minorca gave Britain permanent access to the Mediterranean, enabling the Royal Navy to swiftly counter the French fleet at Toulon in the future. Port Mahon also strengthened Britain’s commercial position, providing a base of operations for warships that could secure and escort the lucrative Levantine trade. Additionally, Minorca improved access for British merchants to southern French and Italian markets. When peace talks were initiated, sovereignty over Minorca and Gibraltar became key objectives of the British delegation. The Allies were in no position to deny Queen Anne’s wishes, being heavily indebted to Britain financially. Possession of Minorca was a landmark event in British imperial history, cementing Britain’s naval presence in the Mediterranean for most of the 18th century.

Olivier Goossens

Sources:

- Falkner, J., The War of the Spanish Succession: 1701-1714, 2015.

- Gradish, S., “The Establishment of British Seapower in the Mediterranean, 1689-1713”, Canadian Journal of History, Vol. 10, 1975, pp. 1-16.

- Karges, C., “Britain, Austria, and the ‘Burden of War’ in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708”, International Journal of Military History and Historiography, Vol. 39, 2019, pp. 7-33.

- Rodger, N.A.M., Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649-1815, 2006.

- Wilson, B., Empire of the Deep: The Rise and Fall of the British Navy, 2013.

Leave a comment