In July 1956, the anti-imperialist leader Gamal Abdel Nasser ordered the nationalization of the Suez Canal Company, a joint British-French enterprise that had controlled this vital link between East and West since its construction in 1869. Britain had extensively used the canal to build and maintain its vast empire. The Egyptian president, however, sought to completely expel British and French influence from the region. The two European powers, fearing that this move might encourage other anti-imperialist movements in the Middle East, decided to intervene militarily. A vast Anglo-French task force was assembled to counter Nasser.

When Prime Minister Anthony Eden’s government decided to act, several challenges arose. Since the Korean War, the Royal Navy had scaled down its power. The navy’s amphibious capabilities, the state of the Royal Fleet Auxiliary, and the equipment of the Fleet Air Arm had all been largely neglected. To mount a proper response, Britain had to reacquire sold equipment and press ships destined for the scrapyard back into active service. British reserves were also mobilized to ensure enough troops were available for the task ahead.

It took about three months for the British and French to gather sufficient ships to launch the operation. This delay proved costly, as by then, international opinion had shifted in Nasser’s favor, with both the Soviet Union and the United States pressuring the two European powers to back down. Nevertheless, Anthony Eden and French President René Coty, determined to demonstrate that their countries remained global powers, proceeded with the operation.

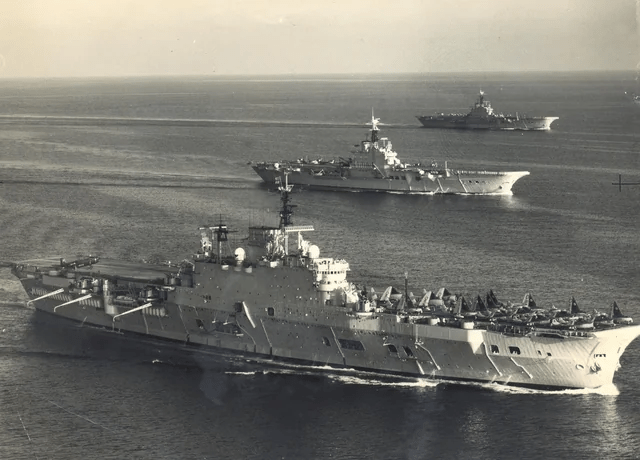

The armada assembled for the Suez invasion included three major British carriers—HMS Eagle, Albion, and Bulwark—as well as two light fleet carriers, HMS Ocean and Theseus, both converted into amphibious assault ships. Theseus and Ocean would make military history by conducting the first-ever amphibious helicopter assault, deploying Whirlwind helicopters to transport Royal Marines and 45 Commando into the battle zone.

The escort force was substantial: three British cruisers, 13 destroyers, six frigates, 17 landing vessels, five headquarters/maintenance vessels, 15 minesweepers, and 24 Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) vessels. A large French naval contingent (Force Navale d’Intervention) further reinforced the fleet, contributing 47 warships, including two strike carriers (Arromanches and La Fayette) and one battleship.

In total, 13 Fleet Air Arm (FAA) squadrons were deployed, primarily operating the outdated Sea Venom and Sea Hawk jets. These aircraft were inferior to the Egyptian MiG-15s and MiG-17s. To compensate, Britain aimed to overwhelm Nasser with numerical superiority, deploying approximately 200 RAF fighters and bombers, including the latest Valiant strategic bomber. These aircraft would operate from Malta and Cyprus, where airfields first required significant upgrades to support combat operations.

On the ground, Royal Marines received support from the Parachute Regiment. However, the unit was underprepared, having had limited training opportunities since World War II.

Help also came from another quarter, as Israel aligned itself with the Anglo-French cause. The Jewish state viewed Nasser as a grave threat to its national security, fearing he might rally the Arab world against the young democracy. Seeing Anthony Eden’s attempt to overthrow Nasser as a golden opportunity, Israel sought to further solidify its position in the Middle East.

Israel and the two European powers agreed on a straightforward plan: Israel would invade the Sinai Peninsula with ten brigades, prompting Britain and France to intervene under the pretext of protecting the Suez Canal Zone. French and British ground and carrier-based aircraft would first strike Egyptian airfields, aiming to neutralize Nasser’s air force as quickly as possible. Then, ground forces would secure the strategic ports of Port Said and Port Fuad, ensuring swift control of the Suez Canal Zone.

The Israelis launched their invasion on 29 October, after which the British and French began their devastating air attacks. The Fleet Air Arm (FAA), in particular, worked relentlessly to neutralize Nasser’s air capabilities. British carrier-based pilots averaged 2.8 sorties per day, compared to the Royal Air Force’s 1.4 sorties. The Egyptians, unwilling to risk their valuable MiG fighters, chose to relocate them to neighboring countries rather than engage in direct combat.

On 5 November, the second phase of the operation began as British and French forces landed their troops by air and sea. They successfully secured the Suez Canal Zone. Losses were relatively light: 22 British, 10 French, and 172 Israeli soldiers lost their lives. Egyptian casualties were far higher, with estimates ranging from 1,650 to 3,000 soldiers killed. Additionally, most of Egypt’s tanks and aircraft—except for the previously mentioned MiGs—had been successfully destroyed.

U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, eager to distance himself from the colonial actions of his allies, continued to pressure Britain and France. He even threatened to sell off U.S. holdings of British pound sterling bonds, a move that could destabilize the British financial system. Under American pressure, the United Nations ordered the immediate withdrawal of all Israeli and European forces from Egypt. This retreat was a humiliation for Britain, leading to Sir Anthony Eden’s resignation as Prime Minister. The Suez Crisis marked the decline of British and French influence in the Middle East, while Nasser emerged as a hero of the Arab world.

From a naval perspective, the operation exposed several weaknesses in British naval strategy. The slow assembly of the Anglo-French task force gave the world time to rally behind Nasser and ultimately forced Britain and France to abandon the canal. Another critical shortcoming was the lack of helicopters with sufficient carrying capacity for large-scale amphibious operations. The Royal Navy also recognized that the success of its carrier jets was largely due to Egypt’s MiGs being absent from the battlefield—highlighting the urgent need for modern carrier-based aircraft. Furthermore, both landing craft and Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) vessels required immediate upgrades, as many RFA ships were pre-World War II relics.

There were also some valuable lessons to take away from the crisis. Despite being a political debacle, the Suez Crisis was, in purely military terms, a significant success for the British and French. It once again demonstrated the crucial role of naval power in rapidly addressing overseas challenges, even in the evolving post-World War II landscape. The Anglo-French task force swiftly secured its military objectives with little serious opposition from the Egyptians.

The Royal Navy’s carriers proved their effectiveness, with their steam catapults and angled decks enabling Fleet Air Arm aircraft to achieve exceptional sortie rates. Additionally, the crisis marked a turning point in modern warfare by highlighting the helicopter’s potential as a military asset. It demonstrated how helicopters could efficiently transport troops to key strategic locations, revolutionizing amphibious operations.

Olivier Goossens

Leave a comment