In the Royal Navy during the Age of Sail, warrant officers were a diverse group of officers appointed by a warrant from the Navy Board. They included surgeons, gunners, pursers, and carpenters—positions that required a relatively high degree of practical skill.

While their appointments were not as prestigious as commissions from the Admiralty, these warrants nevertheless protected them from being disrated or transferred to another ship at the captain’s discretion. All warrant officers were quartered together in the wardroom and held more or less equal rank, except for the master, who clearly stood at the top of their hierarchy.

The master was the most senior warrant officer and was part of a warship’s chain of command. His social background was often that of an experienced merchant with strong navigational skills. Masters were frequently promoted from the ranks of master’s mates, quartermasters, or midshipmen. Before attaining the position, a candidate was examined by a jury consisting of one senior captain and three masters at Trinity House.

In 1753, a second master was introduced aboard the first three rates of ships of the line. In most cases, they were master’s mates who had successfully passed their examination for master. They assisted the master in his daily duties, as the workload aboard such a large vessel was deemed too great for one man alone. Promotion from master’s mate to second master entailed a significant pay increase to £5 5s per month.

The master was responsible for commanding the vessel during more challenging maneuvers, such as tacking (turning into and through the wind), anchoring, and docking. His day-to-day duties included determining the ship’s position on the world map and recording it in the official log. For this purpose, he had a small cabin next to the captain’s, equipped with charts and navigational instruments. He also set the sails according to the required course and conditions. Additionally, he conducted daily assessments of the sails, masts, ropes, pulleys, and anchors to ensure their proper condition.

Another responsibility was overseeing the stowage of the ship’s hold. He ensured that the necessary supplies for sailing were present while also maximizing storage efficiency. Excess weight, in fact, could negatively affect the ship’s sailing qualities.

The master often had no formal education before entering the navy. His navigational expertise was gained through years at sea from a young age. This posed several challenges, as the Nautical Almanac of 1767 was difficult to understand for those without formal schooling.

The master, however, continued to enjoy a good reputation, and the captain often took his advice to heart. Ignoring his counsel was usually unwise, as demonstrated by the case of HMS Pembroke (60), which was wrecked in 1749 after the captain angrily dismissed his master’s warning about the ship’s dragging cable. The captain of the Pembroke perished in the disaster.

A notable and celebrated example of an able master is James Cook, who voluntarily joined the navy in 1755 after a career in the coal trade and an apprenticeship with a Whitby shipowner. He quickly demonstrated his skills, earning promotion to master’s mate within a month and becoming a master within two years. During the Seven Years’ War, his navigational expertise helped Saunders’ fleet reach Quebec through the perilous St. Lawrence River in 1759.

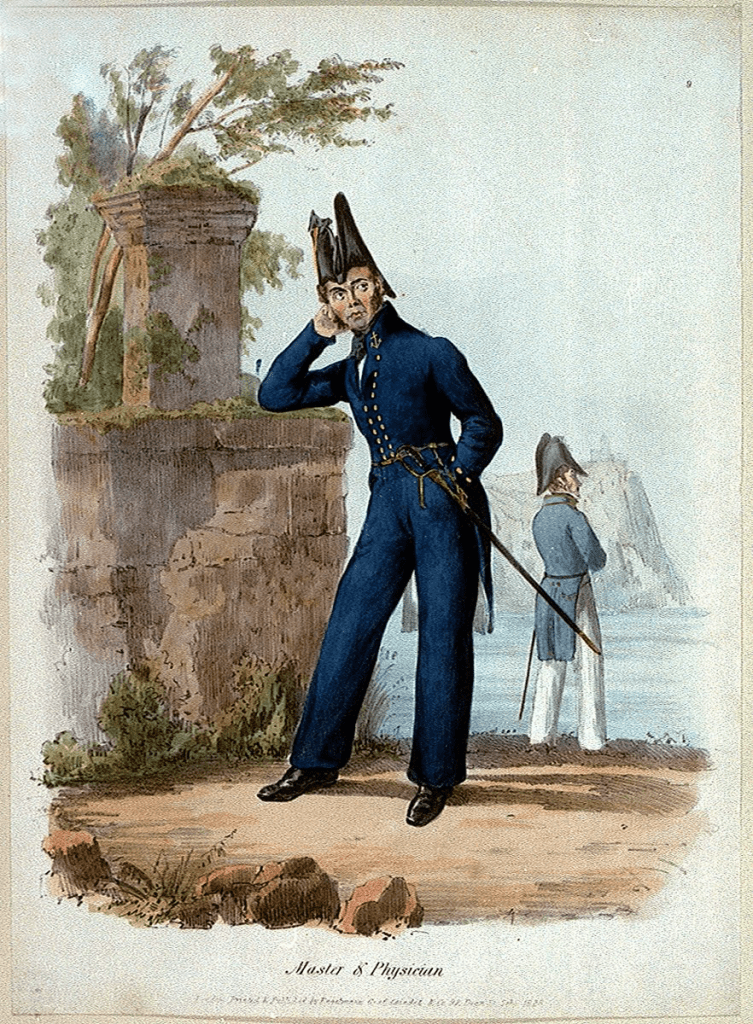

Initially, a master did not have an official uniform. One negative consequence of this was confusion among the enemy, who did not recognize them as befitting their actual rank. This changed in 1787 when wardroom officers began receiving a regular uniform.

During battle, the master stood on the quarterdeck beside the captain. When not on duty, he dined in the wardroom with the other officers above the rank of midshipman. He resided in a large cabin in the gunroom.

By the early 19th century, the number of masters decreased as more of their responsibilities were transferred to other executive officers. Throughout the Victorian Era, wardroom officers became commissioned officers. The title of master was eventually phased out in the modernizing navy after 1862, under the First Lord of the Admiralty, the Duke of Somerset. The last masters were warranted in 1883, and the final one retired in 1892.

Olivier Goossens

Leave a comment