In 1779, during the American Revolutionary War, the Americans assembled a naval armada known as the Penobscot Expedition. This fleet comprised 40 vessels—18 armed warships or privateers and 22 schooners or sloops serving as troop transports. It was the largest American fleet assembled during the Revolutionary War, setting sail on July 19 from Boston and heading toward Penobscot Bay in Maine.

This ambitious expedition consisted of over 1,000 marines and militiamen, along with a 100-man artillery detachment led by Lt. Colonel Paul Revere. Command of the land forces was given to Brigadier General Solomon Lovell, while Commodore Dudley Saltonstall led the naval armada. However formidable they may have seemed, most of the men were unversed in the art of amphibious warfare on hostile shores. Their mission? To reclaim mid-coast Maine from the British, who had captured it and renamed it “New Ireland.”

The British had secured the Penobscot Bay area in June 1779, with General Francis McLean establishing fortifications on the Bagaduce Peninsula, including Fort George. This strategic stronghold marked the beginning of the British plan to establish the colony of New Ireland. This new colony had three main purposes: to provide the Royal Navy with a base on the northeastern American coast to protect Nova Scotian shipping from New England privateers, to block any potential American overland invasion of Nova Scotia, and to offer a safe haven for British loyalists in the region.

The American forces arrived in late July, aiming to besiege Fort George. However, conflicting leadership between Brig. Gen. Solomon Lovell and Commodore Dudley Saltonstall hampered the campaign’s progress. Saltonstall’s indecision would ultimately lead to disaster.

The siege dragged on for nearly three weeks with little success. The British garrison held firm under Gen. McLean’s command, resisting the American assault and buying time for British reinforcements to arrive.

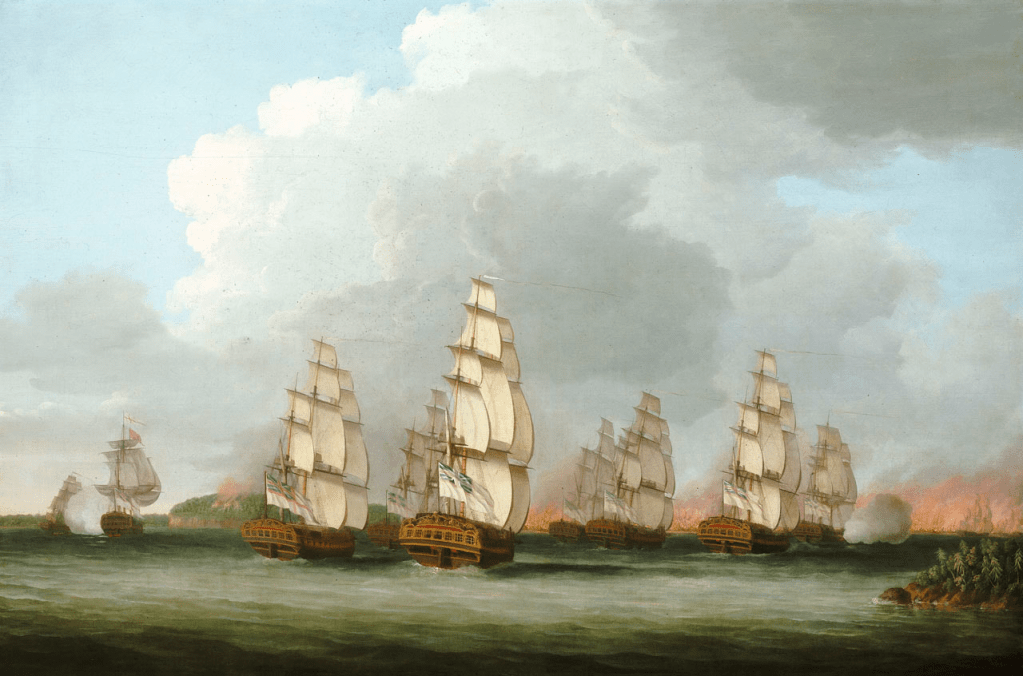

On August 13, a British relief fleet under Sir George Collier sailed from New York, decisively shifting the balance. The American fleet, facing overwhelming force, attempted to retreat but was relentlessly pursued up the Penobscot River.

The result was catastrophic: the American fleet was destroyed in what would be the United States’ worst naval defeat until Pearl Harbor, over 160 years later. Surviving soldiers were left stranded with minimal food and supplies.

The failed expedition led to harsh consequences. Saltonstall was dismissed from the Navy for incompetence, and the survivors made a grueling overland retreat back to Massachusetts. Historian George Buker suggests that Saltonstall may have been unjustly blamed for the defeat. Buker argues that Lovell and others misrepresented Saltonstall, making him a scapegoat for the campaign’s failure, despite Saltonstall’s tactically sound decisions considering the geographic and military conditions in Penobscot Bay. Under the terms of the 1783 Treaty of Paris, British forces evacuated Fort George, followed by about 600 Loyalists who relocated to St. Andrews on Passamaquoddy Bay, effectively ending British efforts to establish New Ireland.

Olivier Goossens

Leave a comment