The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th century (1652–1674) saw an unprecedented number of ships and men engaging in large-scale fleet battles off the coasts of England and the Netherlands. After these engagements, large groups of prisoners of war were disembarked at various seaports in both nations. How were they treated? How did the respective governments handle them? This will be today’s subject on Heart of Oak.

Both sides saw prisoners of war primarily as bargaining chips. Even in seafaring nations like Holland and England, able seamen were a rare commodity. Many perished in the cataclysmic naval battles or from the various diseases that sometimes decimated warship crews. Consequently, both nations highly valued prisoner exchanges. Large groups of captured sailors were frequently swapped throughout the wars, and at times, individual exchanges were arranged for particularly valuable men. For example, in 1666, a deal was struck to exchange the skilled Plymouth surgeon James Yonge for a kinsman of the secretary of the Admiralty of Rotterdam.

Sometimes, prisoner exchanges were not enough to resolve the pressing manpower shortages that frequently arose during wartime. One remarkable episode recounts how the English government promised liberty to Dutch captives on the condition that they manned British merchant ships.

Due to the high demand for prisoner exchanges in both countries, prisoners of war were generally treated in a manner that ensured their survival and well-being whenever possible. Both sides feared that blatant mistreatment could provoke retaliatory violence against their own captives. As a result, the governments took measures to minimize abuse and intentionally spread stories of how well their prisoners were treated. In some distant parts of the world, far from the central control of Amsterdam and London, cases of extreme mistreatment did occur, however. For example, Edward Barlow, who was captured by the Dutch in the East Indies in 1672, was forced to work in the fields of the Batavia colony, where beatings and verbal abuse were a frequent reality for the poor soul.

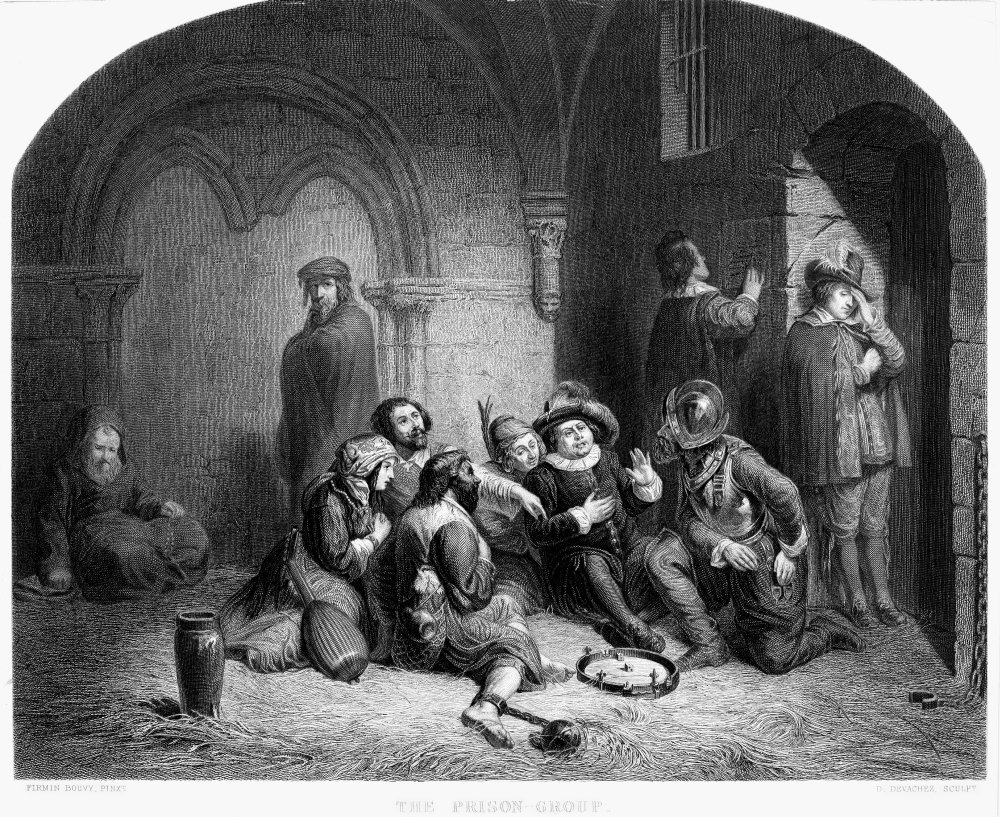

Despite the captors’ abstention from beatings and verbal abuse, accounts from imprisoned sailors still reveal the harsh reality of captivity in 17th-century Europe. James Yonge was one of 160 seamen interned in the “West India Packhouse” in Amsterdam, a room filled with foul oozes and odors, primarily emanating from an open toilet at one end of the building. He was later transferred to an even smaller room in the Admiralty building in Rotterdam, where comforts like tobacco and alcohol were even harder to obtain.

The provisions the sailors received were barely enough to survive. James Yonge informs us that they were given a “threepenny loaf,” two ounces of butter, three ounces of cheese, and a small amount of beer every two days. For extra rations, the seamen had to pay from their own pockets. Yonge was fortunate enough to be acquainted with a Rotterdam merchant through whom his father sent extra cash. However, as one can imagine, many of the British sailors could not boast the same advantage and were at the mercy of the rations provided by their Dutch captors. If you’d like to know more about James Yonge’s life, I suggest reading Noël Poynter’s edition of “The Journal of James Younge, Plymouth Surgeon”. In any case, King Charles II became concerned about the fate of his sailors across the Channel and decided to enhance their well-being through his own funds in November 1665. However, this decision notoriously led to even fewer rations for the Dutch prisoners in his own country.

In any case, officers were given far better treatment and nourishment. In 1672, Captain Fletcher of the fifth-rater HMS Little Victory, was captured by the Dutch and he had to spend his days of imprisonment in a room he only had to share with a French merchant captain. Sir George Ayscue, a British flag officer captured in 1666, resided in the Castle of Louvestein, a place normally reserved for the foremost political prisoners of the Netherlands. Propaganda in both countries, however, sought to paint a different picture. Sir George Ayscue was allegedly paraded through the streets of The Hague with a tail attached to his back. However, specialist J.D. Davies has shown that this was merely a product of the English public imagination.

One major challenge for prisoners of war was getting home. The government did not organize expeditions to extract exchanged prisoners, so the released sailors had to find their own way back to England at their own expense. During the Second Anglo-Dutch War, in June 1666, for example, many sailors were left stranded on the beaches of Ostend. They pooled their money together to secure a ride home. One remarkable tale is that of six men from HMS Leopard, who were captured during the Battle of Leghorn, off the Italian port of Livorno, in 1653. Once released, they had to find their way home and decided to take the overland route of some 1,200 miles through Germany. In an era before modern transportation, this would have seemed a world away.

This only shows one side of the story, namely that of the English. But how did Dutch prisoners in England fare? Certainly, after the successes of the First Anglo-Dutch War (1652-54), the English government was confronted with unprecedented numbers of prisoners. Several large buildings were converted into “prisoner of war camps,” such as Chelsea College and Colchester Castle. By the end of the first war, the “Commission for the Sick and Wounded, and for the Care of Prisoners” was founded to address this issue. During the Second Anglo-Dutch War, once again, thousands of prisoners flooded English port towns. Chelsea College once again served as a prisoner of war camp. In the summer of 1665, however, plague broke out among the prisoners at Chelsea College, and they were moved to Portchester and Leeds Castles. By the end of the year, the Privy Council took over Sudbury Priory to accommodate the many prisoners. After a few months, however, the locals began to complain about the overwhelming number of foreigners in the town. In more distant parts of Britain, local authorities had to improvise to accommodate the prisoners. In Kilkenny, for example, 33 Dutchmen were placed in the town’s inns. Additionally, the first precursors to the “prison hulks” appeared: moored ships in which the captured sailors were kept, often under abysmal conditions.

In general, prisoners were given a daily allowance of four to five shillings. During the Second Anglo-Dutch War, however, this was reduced to the bare minimum of one to two shillings a day. Living conditions could be extremely poor, with diseases breaking out periodically due to the cramped conditions within the prisons. Consequently, escape attempts were made from time to time. The Dutch prisoners were sometimes quite inventive in their modes of escape. At Chatham in 1666, eight members of a Dutch privateer crew escaped through the toilet chute of the prison. Not all attempts were successful, however; some drowned in the moats surrounding the prison camps, while others were shot. This was the fate of the rank and file, but Dutch officers were generally well-treated, much like their English counterparts across the Channel. Some even resided in the houses of English captains.

The costs of confining such large numbers of men were staggering. Initially, the government thought it could manage through the income from prize money, but this proved overly optimistic. The English, with a sigh of relief, set their prisoners free immediately after the war ended. As J.D. Davies points out, during the Third Anglo-Dutch War, the Royal Navy performed far less successfully than it had in the past, which led to fewer prize ships and captured crews. From a purely financial point of view, however, this could be considered a “blessing in disguise.”

In short, both the Dutch and English governments were concerned with the survival of their prisoners of war. This concern was driven as much by practical considerations as by Christian motives. Manning problems pressured both the English and Dutch to ensure the return of their sailors. However, the prisoners were often confined with little dignity: they lived in cramped, unhygienic conditions, and their rations were just enough to keep them alive. One could argue that this was not necessarily due to a lack of humanity, but rather a result of poor organization on the state’s part. We are dealing with an early modern society, where ad hoc problems caused by war were not as easily or rapidly solved as they are in today’s world. The English and Dutch governments simply did not have the financial means or infrastructure necessary to accommodate such large numbers of prisoners.

Olivier Goossens

Leave a comment