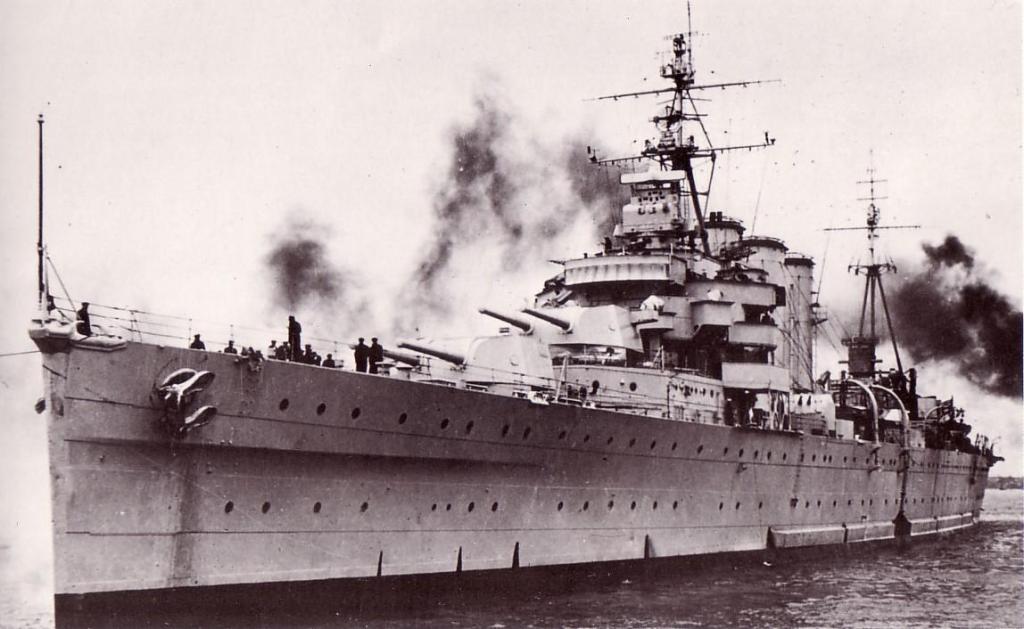

Of the 13 County-class heavy cruisers built, two were designated for the Australian Navy. Both belonged to the Kent subclass. HMAS Australia was launched on 24 April 1928, about two months before her sister ship, HMAS Canberra. Captain Francis H.W. Goolden, RN, was honored as her first commander.

Her early months in service were marked by a special occasion: the visit of King George V on 17 July. After conducting trials in British waters, she departed Portsmouth for Australia via the Panama Canal, arriving in Sydney on 23 October.

During her first years in service, she primarily operated in home waters, with visits to some Pacific Islands in 1932 and New Zealand in 1933. In December 1934, she exchanged duties on the Australia Station with HMS Sussex, arriving in Portsmouth on 28 March 1935.

Two months later, she was assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet under Captain Herbert Forster, MVO, RN, where she served for just over a year. After her deployment in the Mediterranean, she returned home following two years of exchange service. Upon returning to Australia, it was business as usual: cruising in home waters with occasional visits to some Pacific Islands and New Zealand, before being paid off into reserve on 24 April 1938.

She was recommissioned in August 1939, with war looming over the horizon. She remained at the Australia Station for the first few months before being sent off to perform convoy duties, first in the Indian Ocean and then along the West African coast, where she fired her guns in anger for the first time.

Off West Africa, Australia, along with other Royal Navy units such as the carrier HMS Hermes, was tasked with keeping a close watch on the French fleet in the colonies of her former ally, now under Vichy control. During this time, she was attacked by an enemy bomber, but fortunately, no hits were scored on the Australian cruiser.

After so many years in warmer climates, Australia had a short and relatively uneventful deployment in the colder north, patrolling off Norway. She came close to having her first encounter with the Germans during a search for the Gneisenau, but the German battleship managed to elude British forces.

In September 1940, Australia was off again to the West African coast to assist in Operation Menace. The objective was to install Charles de Gaulle and a Free French force in Dakar, anticipating a German takeover of the Vichy colonies in the near future. The task force expected no serious resistance from Dakar, but this proved overly optimistic as shore batteries opened fire, damaging Cumberland and Foresight. Australia and her comrades responded by firing on a French destroyer, reducing it to a blazing wreck. On 24 September, the fleet targeted the port itself, bombarding the forts and ships guarding the harbor. The French retaliated with their bombers, but Australia emerged unscathed. The following day, 25 September, Australia engaged some French cruisers. She was hit twice, and her Walrus patrol seaplane was shot down before the ship was forced to retreat. The entire operation ended in failure.

The Australian vessel resumed escort duties after the debacle in Senegal. She rescued nine survivors from a downed Short Sunderland in storm-force winds and heavy swells. Liverpool then became Australia‘s homeport for several months while she underwent a refit. A heavy bombardment of the city caused minor damage to the docked cruiser, but the air raid also led to the disappearance of two of the ship’s cats, who apparently ran off, much to the regret of the crew.

In March 1941, Australia returned to Australia, patrolling the Indian Ocean for the remainder of the year. Her presence in Asia was maintained due to the emergence of a new adversary, Japan, which also attacked the British Empire following their surprise air raid on Pearl Harbor. In February 1942, Australia became the flagship of the ANZAC Squadron, operating from Nouméa, New Caledonia. Challenging months lay ahead for Australia.

She supported the US Armed Forces during their early operations in the Pacific in March and April 1942, attempting to halt the seemingly unstoppable Japanese southward advance. On 22 April, the ANZAC Squadron was reformed into Task Force 44, with Australia retained as flagship. One month later, Task Force 44 was restructured once again, merging with Task Forces 11 and 17 into a new and larger Task Force 17.

She participated in the Battle of the Coral Sea on 7 May 1942, targeting Japanese transports and light cruisers. Later in August, she supported the Americans during their perilous invasion of Guadalcanal, a period during which she, like many others, was subjected to frequent heavy air attacks.

During the early months of 1943, she was primarily on patrol duty in Australian waters and supported the Coral Sea Group, before heading north to shell enemy positions on various Pacific islands.

Another major test for Australia came in October 1944, when she became involved in the largest naval battle in history: the Battle of Leyte Gulf. The outnumbered Japanese Imperial Navy attempted to thwart the Allied invasion of the Philippines, throwing everything they had at their enemy. The battle raged for three days and marked the last time in history that battleships engaged each other.

The Australian cruiser served as the flagship of Task Force 74 under the command of Commodore John Collins. Other units of the Australian squadron included HMA Ships Shropshire, Warramunga, and Arunta. On 20 October, Australia and Shropshire bombarded enemy positions along the coastline of the Philippine island of Leyte in support of the Allied landings there. The next day, tragedy struck when the Australian flagship was hit by a kamikaze at 06:05. Thirty men perished, including Captain Dechaineux. Commodore Collins and 64 others were wounded. Command of Task Force 74 was transferred to HMAS Shropshire. It has been said that this was the first deliberate kamikaze attack on an Allied ship, though this remains a topic of debate.

Australia was escorted back to Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides by HMAS Warramunga for repairs. Captain J.M. Armstrong was appointed to succeed the late Captain Dechaineux as commanding officer of the heavy cruiser. By January 1945, Australia was back on the big stage, supporting the Allied invasion of Luzon Island. There, she was once again confronted by the medieval fervor of the desperate Japanese: suicide pilots repeatedly targeted Australia. The heavy cruiser was hit multiple times between 5 and 9 January, losing 44 men. The attack on Luzon marked Australia‘s last action during World War II, after which she returned home to undergo extensive repairs.

When the war ended, Australia was in the United Kingdom for a refit. She arrived back in Sydney on 25 January 1946 and was paid off, being placed into reserve one month later. The government decided to retain the cruiser after the war, sending her on goodwill visits to New Zealand and New Guinea in 1948 and 1949.

Sometime later, Australia was converted into a training cruiser, sailing to New Zealand as part of the Australia Squadron on multiple occasions during the early 50s. During the final year of her storied career, 1954, the vessel received the Duke of Gloucester’s Cup. She was then at the center of the royal visit to Australia by Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh, escorting the royal couple throughout Australian waters. Her Majesty and His Royal Highness visited the ship and spoke with several of her crew before departing for Britain again.

She was sold to British Iron and Steel Corporation (Salvage) Ltd on 25 January 1955 for scrapping. One of her 8-inch gun barrels has been preserved at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. She had steamed some 477,301 miles since the start of the war. Although her career during the conflict began relatively uneventful, she ended up at the forefront of the war in the Pacific, suffering heavily at the hands of Japanese kamikaze pilots. The story of HMAS Australia stands as a testament to the resilience, bravery, and professionalism of the Australians during the Second World War.

Olivier Goossens

Leave a comment