The man responsible for keeping the ship battle-ready was the “gunner.” He belonged to the corps of warrant officers, which also included the carpenter, purser, and boatswain. These officers operated under a warrant, as opposed to the “commission” held by higher-ranked officers. The gunner, like the other warrant officers, was appointed by the Navy Board. His primary responsibility, as the title suggests, was managing the ship’s ordnance. Gunners were usually former petty officers or able seamen who had risen through the ranks by demonstrating their capabilities, although exceptions existed, with some gunners being former midshipmen.

Aspiring gunners were required to demonstrate their proficiency in specific tasks. First, they needed to prove their skills as capable seamen, a vital qualification since gunners on smaller warships had to stand watch. Second, they had to exhibit specific expertise in handling and operating large guns, for example knowing the correct powder proportions for each piece of artillery. Third, they were required to present their service certificates. Finally, they had to demonstrate literacy and numeracy, essential for managing the substantial paperwork associated with the role.

These qualifications were assessed by three gunners and a “mathematical master,” who certified the candidate’s competence during an examination, as laid down in the 1790 edition of “Regulations and Instructions relating to His Majesty’s service at sea”:

“No person shall be warranted as Gunner of any of His Majesty’s Ships, or, if made Abroad, have his warrant confirmed, before he has passed an Examination through the Several Parts of Gunnery, touching his Qualifications to serve as a Gunner in His Majesty’s Navy, before a Mathematical Master, and three able Gunners of the Navy, chosen by the Commissioner of the Navy residing at the Port, and produces a Certificate from them, that he is fitly qualified to serve in that Station.”

More specifically, when a gunner boarded a ship being fitted out for service, he was responsible for ensuring that the gun carriages were positioned at their respective gun ports and that the reeving of the breechings and side-tackles was correctly done. He was assisted by a small crew known as the “gunners’ mates.” After the carriages were set in place, the dockyard’s storekeeper transported the actual guns to the ship, which the gunner then had to inspect and clean.

He then examined the magazines and tested them for dampness, as moisture was a serious problem for gunpowder and could render it unusable or unreliable. He also ensured that the magazines were covered with felt, a fabric designed to absorb moisture and reduce the risk of sparks. Additionally, he inspected the magazine padlocks to make sure access to this area was restricted to authorized personnel only. Finally, the keys to the magazines were handed over to the captain.

When the gunpowder was brought aboard, it was the gunner’s responsibility to extinguish all the lanterns except those in the light-rooms. Light-rooms in a man-of-war were specially designed compartments adjacent to the ship’s magazines. These rooms served the critical function of providing light to the magazine without introducing any direct flame or spark, which could ignite the highly flammable gunpowder.

When at sea, he had to regularly check the guns and ensure that the proper equipment for handling them was present. He reported the state of the armament to the lieutenants and was expected to instruct the ship’s company on how to handle a gun. In men-of-war, the cannonballs were already prepared for direct use and stored in shot racks running down the ship’s sides along the waterways. He also ensured that the shot was properly scraped and hammered—this, of course, was also the gunner’s responsibility. The gunner also kept an eye on the match tubs, cylindrical containers used to safely store slow matches. “Two lengths” of slow match were to be kept alight at night over a bucket of water.

He was also in charge of other types of ammunition, such as “grape shot,” which he would lay out in the sun to prevent the canvas in which it was stored from rotting. The gunner also had to ensure that hand grenades and powder were supplied to the tops. Furthermore, he oversaw the armourer, who was responsible for cleaning and scouring the muskets and small arms.

Other duties of the gunner included keeping the gun-tackle blocks well greased, turning the powder barrels end for end from time to time to prevent the separation of the nitre from the other ingredients, and preparing a set of cartridges ready for immediate use. During a naval encounter, when all hell broke loose, he was responsible for ensuring a continuous supply of cartridges to the gun crews.

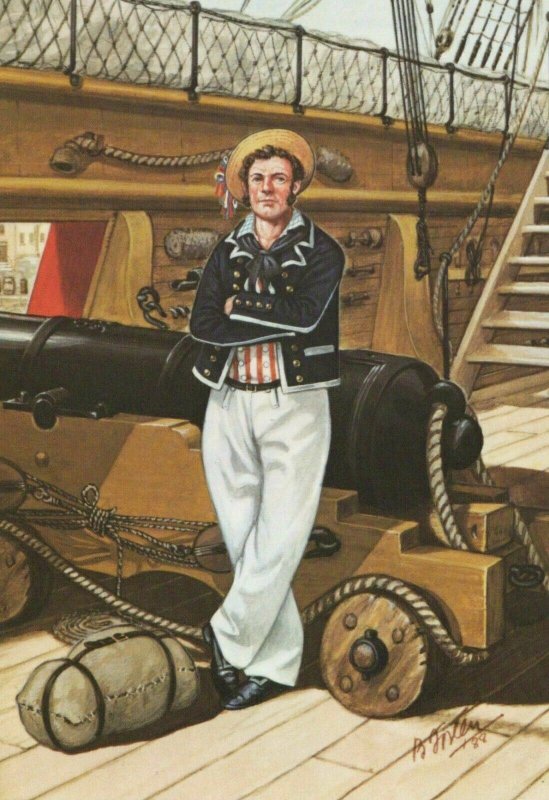

The gunner lived with the junior midshipmen in the gun-room and was assisted by one ship’s boy. His mates, known as “yeomen,” were responsible for keeping his store rooms clean. He wore the same uniform as the purser and the boatswain, which consisted of a white-lined blue coat with blue lapels and cuffs, white kerseymere breeches or trousers, and gold anchor buttons on the pocket flaps. The gunner received the same wages as the purser and the boatswain and received a small perquisite: one shilling for every powder tub returned safely to the storehouse after the ship was paid off. The gunner’s mates, on the other hand, wore no specific uniform but enjoyed minor privileges, such as better sleeping spots.

In short, the gunner was an essential member of the warrant officers, making sure the ship was always battle ready.

Olivier Goossens

Leave a comment