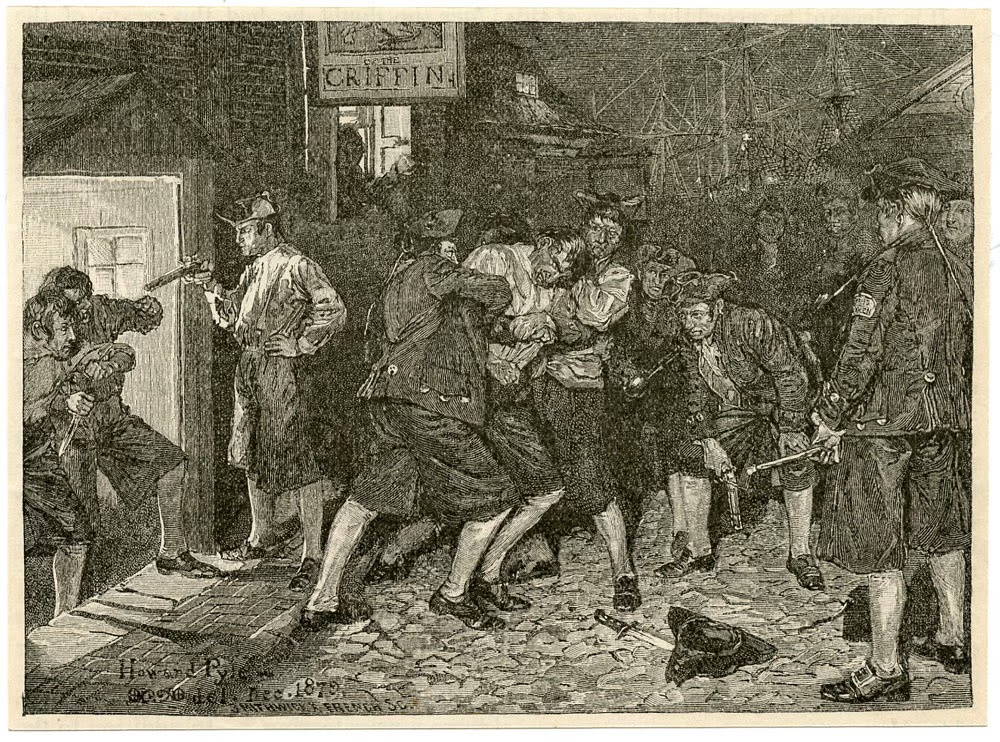

Manning His Majesty’s Navy was always one of the major challenges faced by the Royal Navy. Throughout the 18th century, many sought alternatives to the notorious practice of impressment, wherein press gangs went ashore to forcibly—and sometimes violently—compel idle seamen to enlist by signing their names in the ship’s books. Impressment was widely regarded as undesirable, as it strained social relations with the lower classes in British port towns.

The unpopularity of impressment is evident in the case of Broadfoot in 1743. Broadfoot, a seaman, shot and killed an unarmed member of a press gang. Although the press gang was acting illegally, as noted by the judge due to the absence of their lieutenant, Broadfoot was nonetheless found guilty of manslaughter. There was a public outcry to release the man, who was seen as a defender of liberty.

Many magistrates also detested press gangs for their infringement on individual freedoms and even went so far as to arrest and prosecute their members, thereby sparking conflict with the Admiralty. Renowned naval historian N.A.M. Rodger argues that there was another reason for magistrates to despise the press gangs. In 18th-century England, the state was relatively weak in domestic affairs compared to the powerful local authorities. Consequently, press gangs, acting in the name of the state, were unwelcome guests to local magistrates, who viewed their presence as a challenge to their authority. For this reason, some press gangs even sought a warrant from local authorities to operate in their jurisdiction, although this was legally unnecessary, but -as Rodger (2004, p. 315) notes – it was “politically very wise.”

Many men were pressed at sea by boarding parties as their ships approached British ports. There was no escape for these poor men, but armed resistance was not uncommon. However, when mutiny or any form of desertion occurred, the law stipulated that the sailor’s contract would be terminated and that he would forfeit all his wages. This situation encouraged seamen to accept their fate, as it allowed them to receive their wages before being pressed into service with the Royal Navy. At the same time, merchant ship captains were dissuaded from enforcing discipline, since desertion relieved them of the obligation to pay their seamen’s wages, thereby increasing their own profits.

Many proposed solutions were quickly dismissed as they were either too costly—something Parliament was keen to avoid—or infringed too heavily on the liberties of Englishmen. This was deemed unacceptable, as liberty and the navy were often closely associated, epitomized by the famous line: “Rule, Britannia! Britannia, rule the waves! Britons never, never, never shall be slaves.”

The irony was that Prime Minister Robert Walpole (in office from 1721 to 1742) made genuine attempts to address the problem, proposing several bills that were swiftly rejected for the reasons outlined above. Many parliamentarians chose to ignore the issue altogether, eagerly dismissing any legislation that suggested increasing government spending. They operated under the simplistic belief that, as Britain was a seafaring nation full of traders, a manning problem was inconceivable. However, if difficulties did arise in finding the right men for the men-of-war, the opposition conveniently attributed them to Walpole’s so-called tyrannical inclinations.

Impressment was retained as the perceived lesser evil. To address some of the associated problems, the Admiralty sought to regulate and control the practice more effectively. This effort led to the establishment of the so-called Impress Service, designed to provide the operation with a more legal framework.

In 1745, the first “Regulating Captains” were appointed. Their role was to ensure that press gangs followed the rules and to release individuals who were unjustly pressed, such as non-seamen, seamen already assigned to another ship, or those with valid proof of exemption. The “Impress Service” was, of course, far from foolproof, as corruption and favoritism were rampant—particularly during periods of acute manning shortages, such as the War of Jenkins’ Ear, when disease ravaged the ranks and forced the government to take desperate measures to keep the warships operational. Outward-bound shipping was prohibited unless the captain “allowed” a portion of his seamen to be conscripted into the navy. Nevertheless, impressment remained the primary method of manning the Royal Navy until the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

Olivier Goossens

Leave a comment